GODEY’S LADY”S BOOK

PHILADELPHIA, NOVEMBER, 1852.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PEN AND GRAVER.

BY C. T. HINKLEY

A DAY AT THE BOOKBINDERY OF

LIPPINCOTT, GRAMBO, & Co.

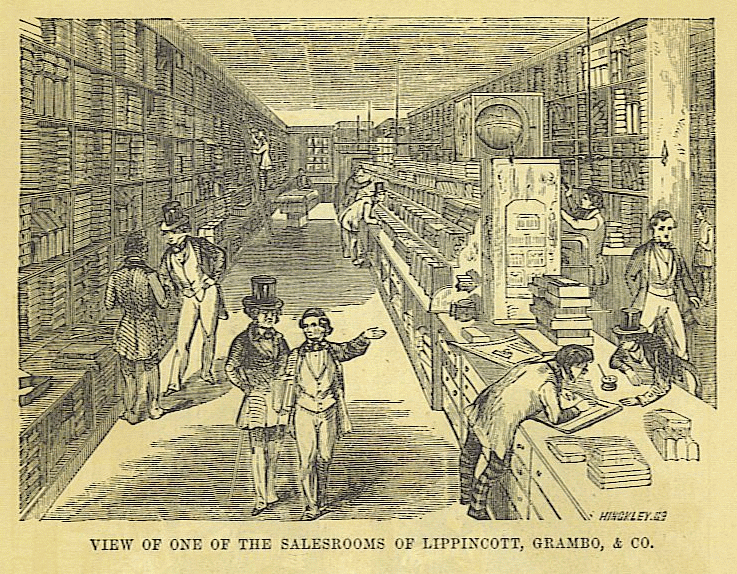

Having given our readers, in our last article, an insight into the mechanical operation required to set the types and print the sheets of a book, we this month take them to one of the largest publishing houses in the country, that they may know something of the manner in which books are bound and circulated through the Union. We are enabled to do this through the courtesy of Messrs. Lippincott, Grambo, & Co., who allowed us the privilege of examining their extensive range of rooms, a general idea of the labor performed in which we shall endeavor to give in the following pages.

When we received the consent of the senior partner of the firm for this privilege, we expected to see much that would surprise us, but were not prepared to find so vast an amount of business performed, or capital invested. We were completely lost in astonishment, as we passed through room after room peopled with workmen engaged in the various branches to which the rooms were devoted.

It was our intention, at first, to give a description of bookbinding only, but were so struck with the extent of labor employed in the establishment, that we have concluded, so far as we are able, to make our readers acquainted with the general machinery of a large publishing house, hoping it may prove as interesting to them as it was to us. We will first describe the

BOOKBINDING DEPARTMENT.

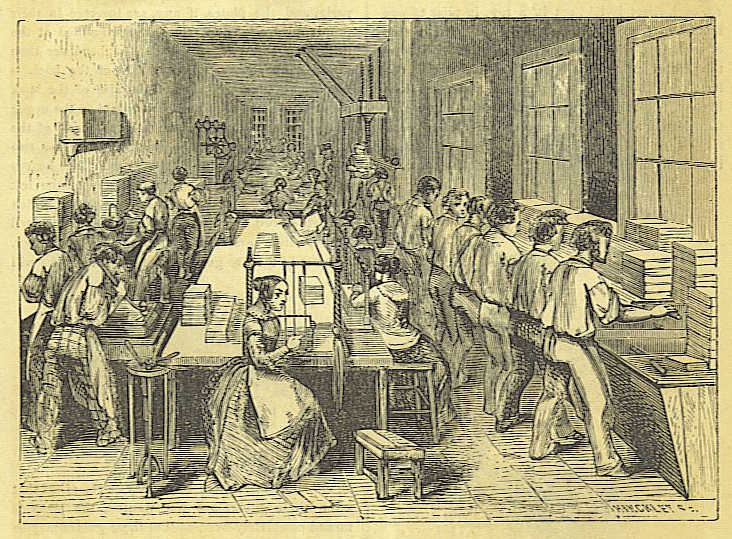

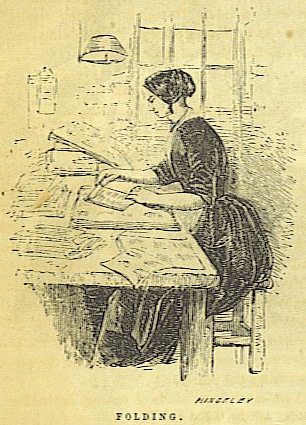

After the sheets are finished in the drying-room, as described in our last, and are pressed, they are sent in bundles to the bindery, where they are opened and given out to the girls employed to fold them.

When the whole of the impression has been folded, each sheet is laid out in a row, in piles of one hundred. The folder then takes one from the top of each pile, and, placing them together, they form the printed matter of a book. The copies thus collected are knocked evenly together, and put into a hydraulic press, between steel boards, in rows of two deep, and as many along-side of each other as the boards will hold, for the purpose of compressing them into a compact form.

If the work be newly printed, care must be taken not to allow it to set off as the fresh ink has a tendency to make an impression on the opposite page, as was generally the case with new books when compressed by the old method, which was to beat them on a large smooth stone with a cast-iron bell-shaped hammer weighing twelve or fourteen pounds. This required some skill so as to compress or condense the sheets without marking them with the edge of the hammer, and to give the paper a smooth polished surface. This process was very much improved some years ago by a rolling-press, consisting of two iron cylinders, mounted and set in the usual way at any required distance apart. A number of sheets, varying from six to fourteen, according to the size, being placed between two tinned iron plates, are passed through the rollers. This method not only renders the paper smoother than by hammer-beating, but the compression of the book is one-sixth greater, a very desirable object, inasmuch as the book-shelves will contain nearly one-sixth more books. These superior effects are also produced by the rollers in one-twentieth of the time required by the hammer. This method is now adopted for books that have been printed some time, in which the ink is properly set, and also for books that require rebinding.

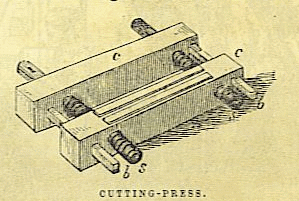

After pressing, rolling, or hammering, each book is collated, to see that all the signatures ran properly, and the plates, if any, are inserted in their proper places. The waste leaves are added at the beginning and end; the back and head are then knocked up square, and one side of the book is placed on a pressing-board of the size of the book itself, and another similar board is laid on the upper side of the book, taking care to let the back of the sheets project about half an inch between the two boards. The workman then grasps the boards firmly between the thumb and fingers of the left band, and lowers them into the cutting-press, which consists of two strong wooden cheeks c c, connected by two slide bars b, b, and two wooden screws s, s. The use of the two guide: on one of the cheeks will

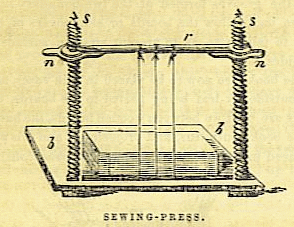

be explained hereafter; but it maybe remarked that when these guides are not wanted, the press is turned completely over, so that these guides may be at the bottom, and out of the way. When the sheet: are lowered between the cheeks c c, the press is screwed up tight by working an iron bar in the heads of the screws. The man then passes a tenon saw across the back of the sheets, so as to make a number of grooves, according to the size of the book, for the reception of the cords or bands for holding the threads in the sewing. and also for securing the boards which are to form the side covers. The number of bands depends upon the style of binding or method of finishing the book ; boarded books, or books bound in cloth, have only two bands. But in the better descriptions of binding, 32mos. sometimes have three bands; 16mos., 12mos., 8vos., and two-leaf 4tos., have four bands; royal octavos and whole sheet 4tos., five bands; and folios from five to seven bands. In addition to these grooves for the bands, a groove is also formed at each end for the catch or kettle stitch. Supposing a book with two bands is to be sewed, it is taken to the sewing-press, which is a stout flat board b b,

This press is arranged for three hands; but for the sake et

simplicity. the description refers to two bands.

containing an upright screw s s at each end, supporting a top rail r, which rises and falls on the screws by means of nuts n n. Attached to this rail are several cords corresponding with the grooves sawed in the back, and these cords are secured by being fastened to brass keys, one of which is here shown, passed through the aperture in the bed of

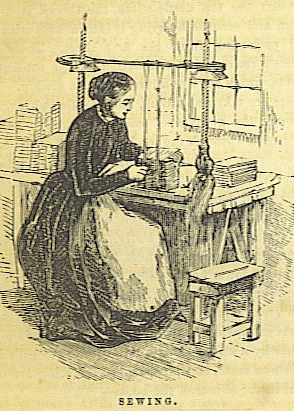

the press, while they are tightened by turning the nuts it it. so as to raise the top rail. The book to be sewed being placed on the board b, with the title uppermost, the sewer first takes the tly-leaf, or end paper, if such there be, or sheet A of the book, and turning it over so that the title-page may lie with its face on the board, she places the grooves in it so as to correspond with the stretched strings or bands. She then passes the left hand into the opening of the sheet, and with the right pushes the needle through the right hand kettle-stitch : the left hand receives the needle, and returns it out through the first groove above the stretched string: the right hand draws the needle completely through, and passes it through the same groove below the stretched string; the left hand takes the needle and passes it through the second groove above the string, and the right hand returns it below the second string; and lastly, the left hand returns the needle through the bottom kettle-stitch. The thread is then drawn so as to lie evenly in the angle of the sheet, a small piece being left projecting through the back at the top kettle-stitch. The sewer then takes the second sheet, and turning it over upon the first, inserts the stretched strings into the sawed grooves at the back.

She passes the needle through the bottom kettle- stitch, and proceeds as before, passing the needle in and out round the bands, only proceeding up the sheet instead of down. When the needle comes out through the top kettle-stitch, the thread is drawn tight, and secured by tying it into a knot with the end projecting from the first sheet. These two sheets form a sort of foundation for the subsequent sheets, which require a less elaborate sewing. Two sheets are taken at a time, and the thread is drawn through the grooves of each alternately : passing the needle through the top kettle-stitch of the lower sheet ; then out above the first band; then into the upper sheet below the first band ; then out above the second band; then below this band into the lower sheet ; then out through the kettle-stitch of the lower sheet ; and, lastly, this lower sheet is secured to the previous sheet by passing the thread round its lower kettle-stitch. Two more sheets are then taken, and in this way the sewing is continued with great rapidity. When one length of thread is nearly exhausted, another is taken, and joined to the former by a knot. This kind of sewing is called op and down work, and presents the following arrangement in the sheets of the book-

the sheets showing two threads and one thread alternately, as the reader will find by examining any boarded book, or a book bound in cloth. When the sewing of one book is completed, the thread is secured at the kettle-stitch, and cut off. A second book is sewed upon the first, upon the same bands, until the press is full. The bands are then loosened by slipping off the keys, and the books are separated from eac-h other by severing the bands, care being taken, for some descriptions of binding to be noticed hereafter, to leave a sufficient portion of the bands projecting on each side of each book for the purpose of securing the boards.

There are various kinds of sewing, depending on the size of the book and the style of the binding. The commonest kind of sewing, such as we have attempted to describe, is called zewing two theets,

up and down work. In some kinds of fine binding, the sheets are sewed nil along, and only one at a time; that is, the thread is passed round every band, so that, supposing there were three bands, the sewing in every sheet would present the following appearance:

![]()

Where it is an object to make the book superior and stronger, fine silk is used, instead of thread. To prevent injury to the book by sawing grooves for the bands, which cause the book to wear out much faster – for the holes thus made gradually enlarge in size until the book falls in pieces – a method of sewing is adopted without any grooves, tapes being used instead of strings. The only holes made in – the sheets by this method are those of the needle, which is passed in and out above and below the tapes, and the sewer forms her own kettle-stitch with the needle.

This kind of sewing is shown above. It requires more care than the former to keep the sheets even, and when well done the effect is excellent, for by this plan the book opens flat at any part, the fold of the sheet starting up fully to view when the book is opened. This style is called flexible binding.