Publisher’s note:

The following text is an excerpt from “The American Handbook of Printing, containing in brief and simple style something about every department of the Art and Business of Printing. 3rd ed. New York: Oswald Publishing Co., 1913.

BOOKBINDING Historical

BOOKBINDING is the fastening together of written or printed leaves in protecting covers. The Babylonians enclosed their clay tablets with an outer coating of clay containing a duplicate impression of the characters of the original tablet within.

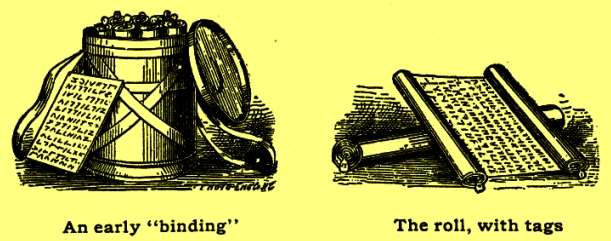

The roll, with tags The Egyptians glued their papyrus sheets together in a long strip and bound them at the ends with a wooden rod, around which the strip was rolled. The Romans also used the roll, but protected it witji covers of leather. The title was written on a piece of parchment and pasted on the cover. For the lesser records the Greeks and Romans made use of tablets of several sheets of thin wood or metal covered with wax and fastened together by rings.

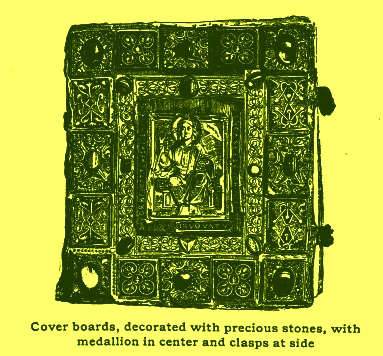

Binding together of the leaves in a flat book displaced the scroll about the Fourth Century. An early method of binding a manuscript book was to wrap a sheet of leather around it, and tie it with a leather thong. Books were laid flat on the shelves, the titles being written on wooden tags hanging from them. Cover boards, decorated with precious stones, with medallion in center and clasps at side Plain wooden boards were next used for sides, and in the Sixth Century these boards (some of which were two inches thick) were gilded, decorated with precious stones, and gold crucifixes were kept in hollows made in the covers.

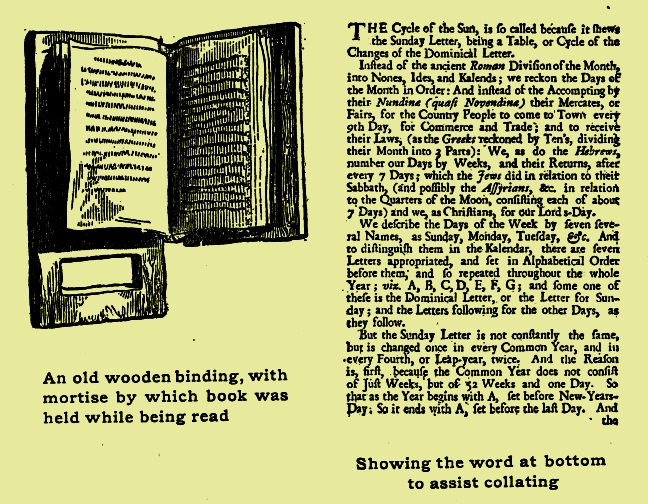

The process of binding books in principle has always been very much the same. The folded sheets were originally sewed to leather bands, the ends of which were fastened to wooden boards, the boards being then joined together and covered with leather. Cords have been substituted for leather bands. Binder’s board has taken the place of wood for the sides, and cloth and paper to a certain extent has superseded leather for the covers. In early books the sections consisted of four sheets folded to make eight leaves. An old wooden binding, with mortise by which book was held while being read The section mark or signature was usually written at the foot of the last page.

To assist in the collation the first word of a page was repeated under the last line of the preceding page. Page numbers, or folios, came into use in the Fourteenth Century, The sawed back (by which method the binding cords were sunk into the leaves of the book) was first used in the Sixteenth Century. In the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries books were covered with velvet, silk and linen. Many of these were embroidered sumptuously. Gold tooling was introduced into Europe late in the Fifteenth Century. Half-binding, of German origin, is a style of binding wherein leather is used only for the backs and corners the parts receiving the most wear.

Carrying economy still further, paper alone was used for covering the sides and back of books, but proving unsubstantial cloth binding was introduced about 1822. Paper labels, containing the titles of the books, were pasted on the cloth backs. Cloth is often used for books when they are rebound in the regulation style of each library. For instance, histories may be rebound in red, poetry in light blue, biographies in brown, etc. Book Collectors and Libraries

Much interest has always been shown in books by enlightened people. Libraries in Egypt contained thousands of papyrus rolls. Ancient Kings accumulated immense libraries of manuscript books, but the contents of such libraries were mostly destroyed through wars and revolutions. The monks not only wrote, decorated, and bound their books, but they were the custodians of the valuable volumes that existed in their time. Corvinus, King of Hungary, in 1480 had a library of fifty thousand volumes in costly bindings.

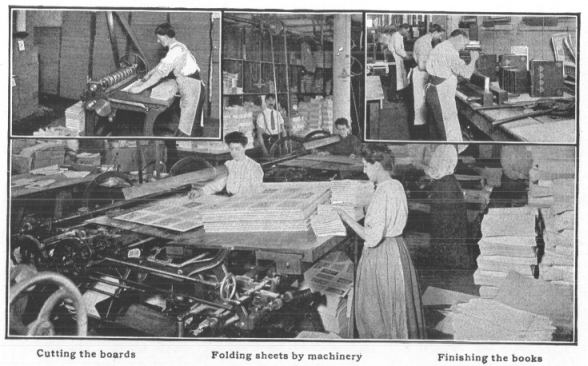

One of the most famous libraries of the Sixteenth Century was that of Cardinal Mazarin at Rome, containing five thousand volumes, one of which was the now famous Gutenberg Bible of Forty-two Lines. Book collectors have always paid great attention to the bindings of books. Many present-day styles are due to the preference shown by such famous collectors as Tommaso Maioli, of Italy, and Jean Grolier, of France, in the early part of the Sixteenth Century. Grolier introduced the style of lettering the backs of books and of placing the backs outward on the shelves. He was also the first to use morocco leather for binding. Many of the old books of value are preserved in the British Museum, but rich American collectors, chief among whom is J. Pierpont Morgan, are buying up scarce volumes in Europe and bringing them to America. Practical Folding Folding, the first stage in the binding of the book, is done both by hand and machine. When folding by hand the operator uses a small bone stick to crease the folds and to slit the sheets to avoid buckling.5 The sheet, or section, of say four, eight or sixteen pages as the case may be, are laid with the signature (or first page of the sheet) face down at the left. The right end of the sheet is brought over to the left and the folios (page numbers) registered with the left hand. The right hand, using the bone, creases the sheet. The top of the sheet is next brought down, registered with the- bottom, and creased. The right end is again brought over to the left, and the sheet creased. The section is now finished, the first page containing the signature. The signature is a small figure or letter placed at the bottom of the first page of each section. A book is divided into sections of, say, sixteen pages each.

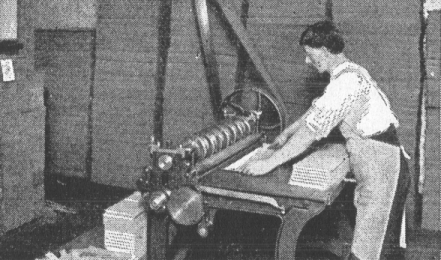

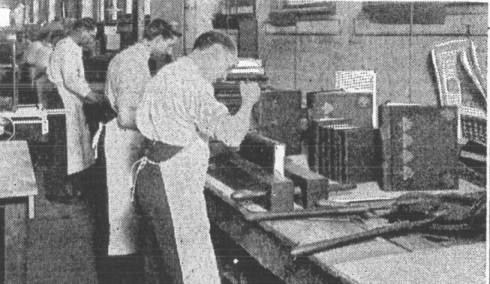

After the sections are folded they are gathered together in the consecutive order of their signatures. It is not well to have too many pages in a section. More pages of thin stock can be folded than of thick stock. When too many pages are folded the paper will wrinkle, or “buckle/’ at the top of the last fold. To prevent this the folder cuts the leaves with the bone more than half way before making the last fold. When sheets are folded on machines, they are fed to “points” to secure register and accuracy in folding. Point holes about fifteen inches apart are punched in the sheets during the process of printing. Gathering The sections are next placed in piles along a table and are gathered one by one, according to their signatures, until a complete book is collected. To expedite this process a moving circular table is sometimes used, the gatherer remaining in one position and taking the sections as they come before-him.

The folded sections, after being gathered, are placed in a machine which applies a great pressure to them, flattening out the creases, forcing the air from between the leaves, and making the book solid and compact. This is also accomplished by beating the folded edges with a ten-pound hammer oh a solid slab of iron or stone.

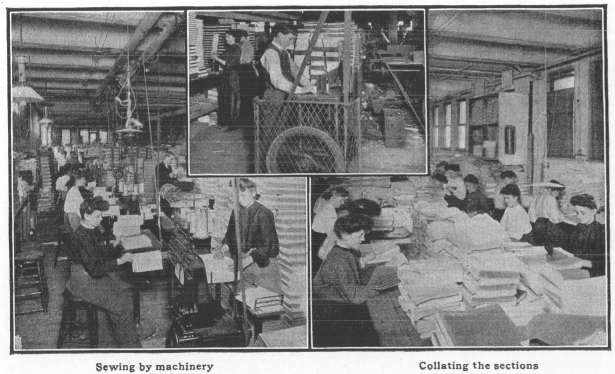

Collating Collating Collating, while often understood to be the gathering of sections, is really the examination of sections already gathered, and the placing of illustrated sheets and maps in position. . The order is verified by the signature on the front The books are next placed under pressure in a standing press for a few hours.

Sawing or Marking the Backs The books are next jogged at the top and back, and boards placed between them an eighth of an inch in from the backs. They are then held firmly under pressure while being marked or sawed for sewing. The backs are sewed at equal distances to admit the cords or bands that are to hold the book together.

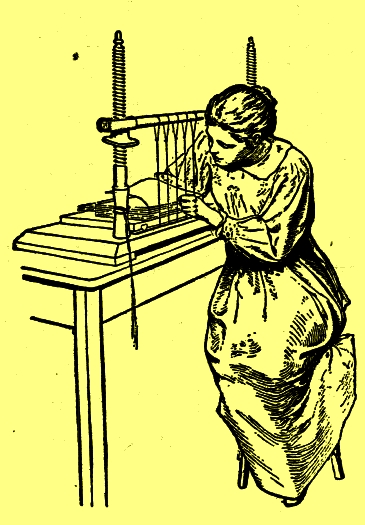

Sewing The sewing press is a simple affair. The cords that are to act as bands are stretched from a horizontal bar down to the base of the machine and drawn taut. The sections of the book are then laid down one by one, the cords fitting in the saw cuts. The threaded needle is inserted in the cut near the head, drawn through to the center fold of the section, and passed around the cords. ‘ Sewing the sections of books The thread is then brought out near the foot, and inserted in another section which has been laid in position.

For the style of binding known as flexible, the backs are not sawed, and the thread is looped around the cords in each instance instead of merely being passed around them. In flexible binding the cloth or leather covering is glued to the back of the book. In ordinary binding, the covering is independent of the back of the book. Machines which sew books automatically are used for large editions.

Forwarding

Forwarding is a term applied to the stage of bookmaking from the time the sewing is finished until the book is ready to be lettered or decorated. End papers, the leaves at the front and back which are pasted to the inside of the cover, are next attached to the book, after which it is trimmed at the top or on three sides as may be desired. The back is next glued and when dry is rounded by beating with a hammer, or this is done by machinery. In old-style binding the backs are left almost flat.

Binder’s board, made from old rope, and boards made from straw, in various thicknesses, are used for covers. Two boards are often pasted together for large books. Ordinarily the boards are covered after being put on the books, but when binding in large quantities, known as edition binding, the covers, or cases as they are called, are previously cut and covered, the thickness of the book having been ascertained.

After the covering material has been glued to the boards, the cases are made smooth by being run through rubber rollers. The cases are next stamped with heated dies in an embossing press. Dies can be made by electrotyping and are known as binder’s stamps. The electrotype is allowed to remain in the battery until it accumulates a thick coating of copper, which is then backed up by a base of lead.

Finishing

There are various ways of finishing the edges of a book. Its leaves may be left uncut all around, the head only may be trimmed, or the leaves may be trimmed on all three sides. Sometimes all edges are left white, or are colored red or blue by being painted with a brush. The edges.of the leaves at the head are frequently gilded, done by sizing the edges with the white of an egg, laying on gold leaf, and burnishing it with a highly polished agate stone.

Religious books are often colored red and then gilded. The real finishing of a book is understood to be the tooling and lettering of the covers. Blind tooling is decoration pressed into the leather without the use of gold leaf. The tools used are: numerous handles upon the ends of which are center and corner designs; wheels containing border designs; and a tool for holding individual types.

Leathers for Binding The several bindings are of value in the order following, beginning with the cheapest: Paper, cloth, roan, skiver (split sheepskin), calf-skin, russia, turkey morocco (goatskin), levant morocco.

Paper, the cheapest binding material, is usually a thin plated paper, coming in various designs, the one known as marble being most popular for blank and check books. Cover paper is much used for artistic work. Cloth, a woven material pressed and embossed in several kinds of finishes, is the most used of any of the binding materials. It is made in numerous colors, shades and designs.

Russia Leather, of Russian origin, is made in brownish-red or black, from the hides of young cattle. It is also manufactured in America and Europe. Imitation Russia Leather is treated with birch bark oil to give it the odor peculiar to genuine russia.

Sheep, chiefly used for binding law books, is the full thickness of sheepskin in the natural color received from tanning, or it may be had in artificial colors and grains. Roan is the inside of a split sheepskin, colored (generally reddish brown, hence the name roan). It is sometimes grained in imitation of other leathers. Skiver, a sheepskin from which the heavy flesh side has been split.

Morocco Leather was originally the product of Turkey and the Levant districts along the Mediterranean. It was made from goatskins, finished in various colors, had a fine grain, was clear in color, and felt soft yet firm to the touch. This leather was much used in the artistic bindings of the Sixteenth Century. As the peculiar grain of morocco leather can be closely imitated on any thin leather, it requires an expert to determine the genuine. The natural leather grain is obtained by doubling the surface and rolling the folded edge with a flat board.

An artificial grain is given leather by embossing. The design, contained in reverse on a metal roller or plate, is pressed into the dampened leather. Uncut Edges Uncut edges are really an affectation. In the days before cutting machines were invented, the sheets were bound just as folded, with unfinished deckel-edges. The books were read in a leisurely manner, and the pages were cut as needed. In these busy days uncut leaves are an abomination if the book is intended to be read. It is not considered good form by some owners of private libraries to possess books which have had their edges cut.

Special editions, finely printed and bound, seem to be made for exhibition purposes only. Magazines are left uncut for commercial reasons. A copy uncut is proof it has not been sold or read.

Sizes of Books In olden times the sizes of books were known by the number of folds to a sheet of paper about 18×24 inches in size. A book made from such sheets folded once into two leaves was known as a folio volume and measured about 12×18 inches. Folded twice into four leaves, a quarto, measuring 9×12 inches. Folded three times into eight leaves, an octavo, measuring 6×9 inches. Folded four times into sixteen leaves, a I6~mo5 measuring 41/4×6 inches. As the several sizes of paper were known by names such as Crown, Royal, etc., the exact sizes of books were known as Crown quartos, Royal octavos, etc. Bibliophiles and librarians still indicate the sizes of books by the old method, but the general public not being familiar with these shop terms, is enlightened only when the sizes are given in inches.

Kinds of Binding The common method of sewing, known as the kettle stitch, as before described, is for regular folded sections, and allows the book to open flat.

Center stitching, similar to the saddle wire stitch, is for pamphlets consisting of all inset folded sheets. The thread is worked through three places in the fold of the pamphlet. If the ends of the thread are to be on the outside, the sewing is begun and ended on the outside and vice versa.

Side stitching (now almost entirely done with the wire stitcher) in the old way was accomplished by sewing through three holes punched with an awl or stabbing machine.

Whip stitching: overhand and cross-lashed stitches on the edges of the leaves, allowing the book to open almost flat. This method is used for books consisting of many single leaves.

Check Binding: Books side stitched, with light straw-board sides covered with paper; cloth or leather back, covers cut flush.

Quarter Binding: Books sewed, with kettle-stitch, strawboard sides covered with paper, leather back, paper turned over edges of cover. Half Binding: Books sewed with kettle-stitch, or whip-stitch tarboard sides covered with cloth; smooth roan leather tight back; paper turned over edges; cover, with or without leather corners, extending over edges of book; lettered on back in gold.

Three-Quarter Binding: Same as half binding except russia leather rounded spring back with raised bands; leather corners.

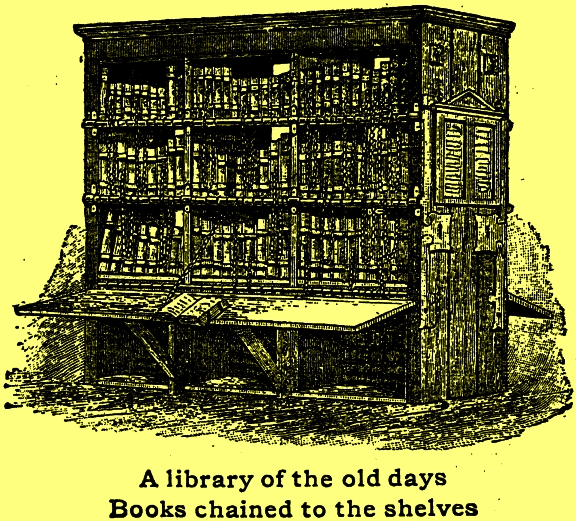

Full Binding: Same as three-quarter, except; that binding is full sheep with russia leather ends and bands; or with double raised bands, double russia side finishing, and lettering. A library of the old days Books chained to the shelves.