BOOKBINDING

BEING DESCRIPTIONS

OF THE VARIOUS TOOLS AND APPLIANCES

REQUIRED MINUTE INSTRUCTIONS

FOR THEIR EFFECTIVE USE.

BY

W. J. E. CRANE.

ILLUSTRATED WITH 156 kENGRAVINGS.

LONDON: L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND.

LITTLE prefatory remark is required in introducing this small book to the public. The present day is especially noticeable for the number of amateur workers who are found in every department of art and technics. That being so, there is certainly no branch of work better fitted to claim their time and attention than that of Bookbinding. It is of great antiquity, of the utmost utility, and capable of almost any degree of artistic development. Looking back to the birth and early history of literature, we find all the oldest manuscripts, both classical and oriental, were written on sheets of parchment or papyrus, and rolled up when not in use. The bookbinder of those days was simply a maker of circular cabinets or repositories, suitable for containing these rolls; and these cases, when for bibliophiles, were often beautifully ornamented. When and by whom the plan of folding the sheet of parchment or paper into pages, and stitching sheets together at the back, was first introduced, is not exactly known; but at that time, and not till then, the book sprang into existence.

This new back required the bookbinder as we know him now; and at the very outset of the trade, his work, though entirely different to the articleic productions of the present day, was elaborate and beautiful. The whole subsequent history of bookbinding has done credit to its brilliant beginning. There are many good reasons for commending this craft to the attention of amateurs, amongst which we will enumerate a few. First, it does not require any great strength or mechanical aptitude. Secondly, the plant is not expensive. Thirdly, it can be pursued anywhere. Fourthly, it is of unquestionable utility: how far preferable it is to have your cherished books, in handy accessible volumes, instead of in heaps of disorderly parts or numbers, almost mere litters, in which one can never find what one wants! Fifthly, and by no means the least important, well-bound books form an ornament to any room, and are satisfactory to show one’s friends. All amateurs are fond of, and proud of, exhibiting specimens of their handiwork to admiring friends and visitors; and what better than books? Fret-cutting, turning, illuminating, &c., are so very common now, that they are almost “played out.” Bookbinding is not so, and if the amateur becomes a good finisher, the amount of varied and interesting ornamentation that he can produce is infinite. In this little volume, full particulars of every process and detail are given, especially adapted to the wants of the amateur. That it may train many skilful articles, is the earnest aspiration of the Author.

INTRODUCTORY

IN the small book, of which this is the preliminary chapter, we purpose to treat, succinctly but completely, of the various practical operations gone through in the binding of books, and in so doing we shall keep the wants of the amateur especially in mind. Unquestionably, the articleic art is one which any intelligent and fairly handy man can practise at home; and as the objects upon which his ingenuity would be exercised come necessarily much into his own hands and those of his friends afterwards, he will often experience the lively satisfaction of being praised for his taste and skill. Bookbinding is a clean and not too laborious occupation, which can be easily practised in any spare room, or even airtight shed where light is plentiful and the temperature can be raised to that of an ordinary sitting-room. “We may premise that, after next chapter, we shall go on to describe, consecutively, the various processes as practised by a professional bookbinder, following each by any expedients which may seem more within the power of the amateur. We shall adopt this course for several reasons. In the first place, it is best that the amateur should understand the correct process as practised by the tradesman, and, where possible, conform to it as nearly as practicable. In the second place, it will render the book a complete manual of the art, useful alike to the amateur or youthful professional workman. We must, at the outset, beg those of our readers who purpose carrying out our instructions to lend their best attention to the subject.

Bookbinding is, undoubtedly, a delicate and a difficult art, and it is almost impossible to describe some of even its simplest processes. In many cases, the slightest deviation from the teaching will risk inevitable failure in the process described; but to make up, as far as may be, for the lack of personal showing “how to do it,” we shall sprinkle our text thickly with sketches of the various operations at different stages, of which we bespeak careful observation. Bookbinding is comparatively a modern art. The books of the ancient and classic nations were, as most people are aware, long rolls of skins or of Egyptian papyrus, which, when not in use, were rolled up and kept each in a species of circular box. When wanted, the roll had simply to be drawn out of its case and unrolled. The Jews use to this day, in their synagogue services, similar rolls of vellum, whereon is written the Pentateuch in Hebrew characters. Doubtless, the earliest specimens of bookbinding were those produced in the eastern branch of the Roman dominions, usually called the Byzantine Empire. These were generally of metal gold, silver, or gilt copper. Of course, this kind of binding was produced by the goldsmith, silversmith, and jeweller, the part of the bookbinder proper being confined to fastening the leaves together and securing them in the metal cover. Of these ancient bindings, some few specimens are still extant. It is difficult to trace the transition of the parchment from the roll form to that of leaves. It is known that the Romans used small tablets of wood, and even leaves of lead, connected by rings at the back, so as to form a small book. Perhaps this gave the hint. It is clear that the book form is more ancient than was at one time believed.

Dr. Hogg says : “Amongst the various objects of antiquity which were purchased from the Arabs, at Thebes, were two papyri, the one in Celtic, the other in Greek, in the form of books. . . . The leaves were about 10in. in length by 7in. in width, and had been sewn together like those of an ordinary book.” Once this step was attained, the covering would quickly follow. In the reign of Charlemagne the art of bookbinding made rapid strides. Italian designers and artificers were employed, and we read of the caskets in which books were preserved as being of solid gold, and covered with precious stones. The clasps of the covers were often closely studded with jewels, and small gold nails were frequently scattered over the leather of which the cover was made. Ivory was also a favourite material for book sides. This was probably derived from the Roman diptychs. The next great step in the history of bookbinding was the general adoption of leather as a covering. Hitherto nearly all the binding had been done in monasteries, and, although they might use velvet, and call in the aid of the silversmith to ornament books bound for princes, yet those of the monastic library were generally supplied with a binding of plain vellum, or enclosed with heavy carved oaken boards of immense thickness. It is not known precisely who introduced leather binding, nor the date of its introduction. It would seem to us to follow naturally on the use of vellum. To Matthias Corvinus, the celebrated literary and chivalrous King of Hungary, the first use of morocco is credited. This may be true of the dressed skin of the goat (morocco), but deerskin had been employed long previous in the monastic binderies. Richard Chandos, Bishop of Chichester, mentions, in his will, as early as the year 1253, a “Bible with a rough cover of skins;” and the ” Accounts of the Households of Edwards I. and II.,” contained in four MS. volumes, presented to the Society of Antiquaries by Sir Ashton Lever, were in the original binding of calfskin, dressed like parchment, but with the hair on, except where it had been removed to give space for the written inscription. It is thus evident that the practice of bookbinding was far advanced at the time of the discovery of printing.

Of course, the introduction of that “art preservative” largely increased books, and hence bookbinding. As far back as the Wardrobe Account of Edward IV. (1480), kept by Piers Courtneys, we find entries for ” binding, gilding, and dressing ” a certain book, and mentions of silk and velvet ” purchased therefor.” Among monarchs, Elizabeth and the first James seem especially well affected towards velvet. Henry VII. appeared to have been the first English king who formed a library, and he had a magnificent one–the books being covered with splendid bindings. Soon after the introduction of vellum, it came into general use (circa 1430), almost ousting velvet, except for livres de luxe. Very soon we find the sides of such vellum books covered with an elaborate stamping of various designs–sometimes crowded and without merit; at others, so sharp, clear and well defined, that they have never been excelled, and scarcely rivalled, by any modern workmen. When we consider that these early binders could not have the aid of the powerful arming presses of to-day, we may well wonder how they managed to impress the large and elaborate blocks with the success to which they attained. James I. appears to have been an ardent bibliophile both before and after assuming the crown of Great Britain, and many of his bookbinders’ bills are extant, showing entries for books bound in leather, vellum, and parchment. Although plain stamping (“blind tooling”) is found very early in the history of leather binding, as is evinced by the vellum and “basil” book covers so ornamented, there seems little doubt that gilding the leather had its origin in Italy, probably Venice, and had been derived by the Italian bookbinders from Eastern sources.

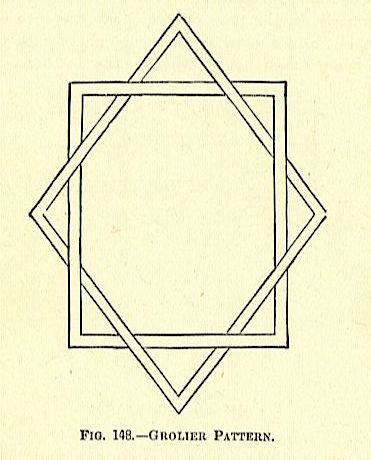

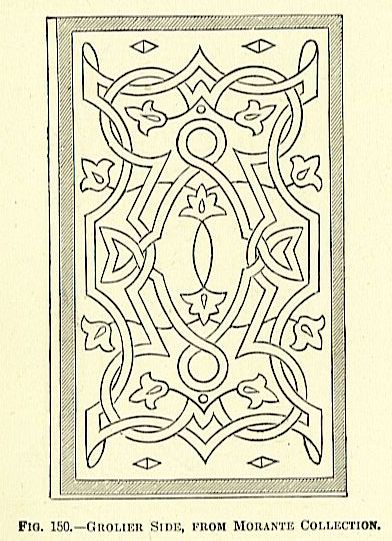

To these same binders we probably owe the initiative of the burst of the articleic glory in the fifteenth century. It was in 1479 that Jean Grolier de Servia, Vicomte d’Aguisy, the founder of French bookbinding, was born. He was himself of Italian extraction, and was sent by Louis XII. to Milan in a diplomatic capacity. Probably he here imbibed his love for fine bindings, for, on his return, his famous library of finely bound books soon became celebrated. Grolier gave an immense impulse to French bookbinding, and appears to have brought Henry II. and his chere amie, Diana of Poitiers, to the same enthusiasm as himself, for they were both lavish in the bindings of their books. Grolier is supposed to have been the first man whose books were lettered on. the back. By the sixteenth century leather binding had assumed its perfected form as seen at the present day, and its subsequent history showed few changes. Amongst those which have taken place, may be mentioned the substitution of ” marbled ” edges for gilded and self-coloured ones, and the introduction of stamped calico (cloth) in the present century by English binders (by Archibald Leighton, in 1825).

The latter, as a cheap medium of binding, is an immense boon, and it is now being slowly adopted in other countries. It is, however, only a temporary vehicle for new books, and can never take any place as a library binding. Let us now, before proceeding to practical details, say a few words on taste in bookbinding. Most book lovers, in all ages, have desired to see their treasured volumes fitly, and even splendidly, clad. Chaucer’s ” Clerke of Oxenford ” preferred to see At his bede’s hede, Twenty bokes clothed in blake and rede, to any other spectacle which the world could afford; and a magnificent binding so enraptured Skelton, the laureate of our eighth Henry, that he asseverates It would have made a man whole that had been right sekely, To beholde how it was garnisshyd and bound, Encoverede over with golde of tissew fine ; The claspes and bullyons were worth a thousand pounde. It is a disputed question, among book lovers of taste, whether the whole of a small collection should be bound in the same material, and of the same colour, or whether a diversity should prevail.

There are valid reasons for either plan. A library where both morocco and calf bindings are adopted, in the various hues which are given to each leather, has a pleasant and lively appearance, and if glaring contrasts in hues be avoided in neighbouring volumes as they stand upon the shelves, an air of lightness and vivacity will characterise the apartment. But the contrast must by no means be too pronounced. Dr. Dibdin, a great authority on all such matters, warns us specially against the employment of either white vellum or scarlet morocco as a material for the jackets of our volumes. Both are too decided in appearance, and impart a “spotty” look to the shelves. Of course, this objection applies only to single volumes or small sets in libraries of limited extent. If, for instance, a whole press, or set of shelves, could be appropriated to vellum-clad volumes of the Fathers and patristic theology, the effect would be good. The decision on the general question of uniformity versus variety must be left, in great measure, to individual taste. Where the collection is small, say, sufficient to fill two ordinary bookcases (about 500 volumes), an excellent plan is to reserve one case for standard

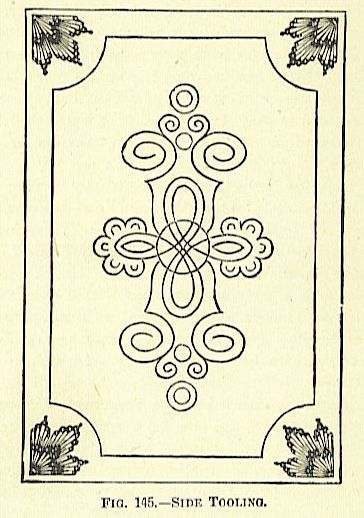

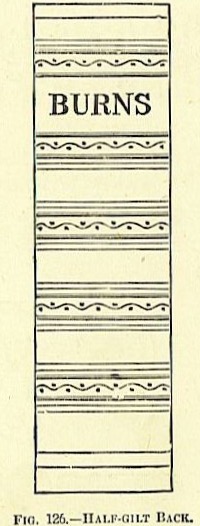

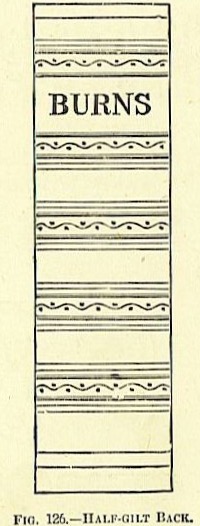

English authors, and bestow in the other works on science, art, travels, foreign books, &c. Let all the bindings be of morocco, either ” whole” binding (the term used when the book is wholly covered with leather), or half binding (where the back and corners only are leather covered, ” cloth,” of a similar colour to that of the leather, being used for the sides), according to the value and importance of the book. If maroon morocco be chosen for the books in the first press, and an olive green for those in the second, the effect will be chaste and massive. Both these leathers ” throw up ” the gilding of the back splendidly. Where expense is not a primary consideration, the backs should not be scrimped in this matter of gilding, or, as it is technically termed, “finishing.” A morocco bound book should bear a good amount of gold on the back; but the patterns of the tools should be carefully selected. For all volumes of tolerable size, a bold, clear style of ornamentation should be adopted, and raised ” bands,” crossing the back of the book, should be a sine qua non with every tasteful bibliophile. Not only should all the books in one case be in the same kind of leather (if the uniform plan be adopted), but the style of “finishing” should be the same. If lines have been chosen as the means of ornamentation, let all the books be decorated therewith. On the contrary, if a more florid style has found favour, let it be adhered to throughout. One of the most effective sets of books that ever came under our notice had all the volumes bound in blood-coloured morocco, richly gilt in the cinque cento style of ornament. The Empress Eugenie is stated to have had her books uniformly bound in sky-blue morocco, thickly sprinkled with the golden bees which form one of the emblems of the house of Bonaparte. It is, however, not unlikely that the amateur bookbinder will introduce greater variety amongst his bindings, for the simple reason that he will be desirous of trying his hand on morocco, calf, roan, vellum, and cloth–all of which we shall, in due course, describe.

TOOLS AND APPLIANCES.

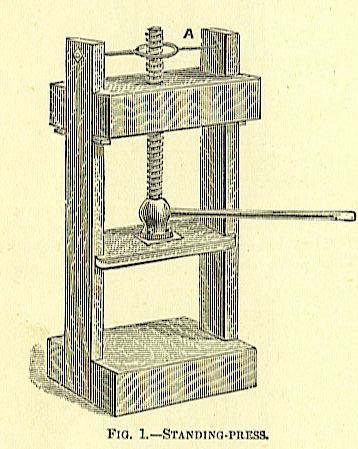

LET us now consider the tools necessary for a small bookbinding plant. The bookbinder’s workshop may be fitted up in any spare room or weather-tight outbuilding. It should always, if possible, be on the ground floor, because the operations of beating, pulling down the standing-press, and even cutting, cause considerable concussion to the walls and joists of the place. The first fixed tool is the common screw ” standing-press,” which is similar to that used by packers, and in the making of cheese and cider. It usually consists of two heavy cheeks of wood, and a head and bed of the same, the whole forming a kind of parallelogram when put together. Through the head passes a brass box, in which revolves a long iron screw, with a tolerably fine thread, and from this screw depends a stout piece of wood called the ” platen,” or sometimes the ” follower.” The books are piled up between smooth beech boards, in the centre of the bed of the press, and the platen screwed down upon them, at first by the hands, then by the short iron press-pin, and lastly by the long one, to which a couple (or more) men lend their force, one pulling and the other pushing.

Sometimes a ” purchase ” is used; this is a strong post, planted in the ground at some distance from the left side of the press. Fixed on this are a cogged wheel, pinion, and handle, which turn a wooden cylinder, around which a chain can coil. The free end of the chain is provided with a hook, and, this being fixed to the end of the long press-pin, when at the right cheek of the press, the windlass handle is worked by one or two men, and as the chain is wound upon the barrel, the pin is necessarily brought over with more power than by muscular effort exerted directly. Standing-presses are also made wholly or partly of iron. The screw of the press should always be kept well oiled, and, to preserve it from dust, it is well to make a paper cylindrical case a little bigger than the screw, and put over it.

The iron ring shown above the press (Fig. 1) is intended to support this standing press pasteboard cap. The press should be firmly fixed by strong timbers braced to the walls and ceiling, in order to hold it quite firm, and resist the shocks of the pulling down. Each press should be supplied with a round piece of wood, about 18in. long, with which to screw it up and down when empty, and a short (4ft.) and a long (6ft.) iron press-pin, fitting the screw socket.

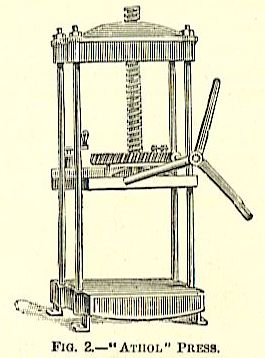

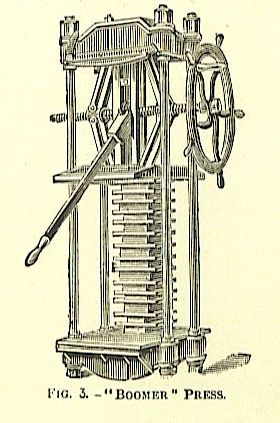

There are several modifications of the screw press, amongst which the ” Athol” press (Fig. 2) possesses much merit, as, from the position of the lever, this press does not jar the premises when fixed so much as the ordinary one, and, moreover, requires no separate press-pin–the Isle of Man legs, Been on the right cheek, being used to pull it down. Another novel and excellent press is the American “Boomer” (Fig. 3).

This press consists essentially of screw pressure applied by a wheel until it is too great, when a lever working a rachet wheel is brought into operation, and a very intense pressure is obtained, stated by the maker to be greater than that of the hydraulic press. With this press also there is but little jar or shock. Of the hydraulic press it is not needful to speak, as that is seldom used except in large establishments, and certainly never by amateurs. The price of a standing-press ranges from £8 for a small wooden press, and from £14 to £26 for an iron one; small Athol, £35; small Boomer, £28. In most cases (unless, indeed, the purpose is to do a great deal of work) it will not be necessary for the amateur to purchase a standing-press. If he beat his books effectually, he can make shift without one. They can be screwed up in the laying-press sufficiently tightly to get much smoothness. A large iron copying-press, or even a good wooden napkin-press, are not to be despised as auxiliaries.

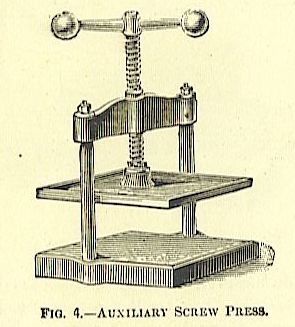

Mr. F. Ullmer, Cross-street, Farringdon-road, and Mr. Powell, 33A, Ludgate Hill, E. 0., keep small iron screw bench-presses (Fig. 4), which would prove very useful, and cost about £5 each.

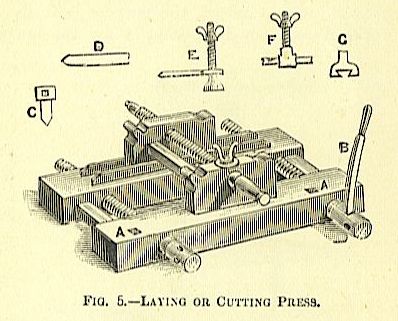

With every standing-press it is necessary to have a good supply of pressing-boards. These are rectangular pieces of beech, from 1/2in. to 1in. thick, planed perfectly smooth and square, and varying in size, from those capable of receiving a folio to those only large enough for a 12mo (these sizes will be explained in due course). Next in importance come’s the lying (or ” laying,” as it is invariably called by the professional bookbinders, which form we shall follow) press (Fig. 5). This consists of two large square cheeks of oak or beech connected by two large wood screws and two guide bars. On one side, which is kept uppermost for general purposes, the cheeks are simply planed smooth.

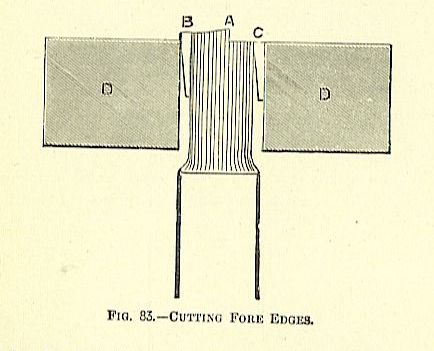

On the other side, however, which is used for cutting purposes, the left-hand cheek has two small pieces, screwed on in such a way as to leave a channel between them, in which the left-hand cheek of the ” plough ” slides in the operation of cutting. When this side is uppermost, the press is termed a ” cutting press” (it is in this position at Fig. 5). This press can be tightly screwed up by the short iron “press-pin” shown at B. When in use, the screws and guide bars should be treated with soft soap and blacklead, or some similar lubricating composition, to allow of their working freely. If the two small square pins or keys (A, A, Fig. 5) be driven out (which can easily be done with a hammer and a square pin of hard wood), the grooves in the screws, in which they work, can also be lubricated. With this press is used the “plough,” a small apparatus of beechwood, shown at Fig. 5. This consists of two flat cheeks, which can be brought together by turning the screw. The right cheek of the plough is furnished with a sharp pointed knife, secured by a screw. When the book is tightly screwed up in the cutting-press, with one of its edges slightly protruding, the binder places the plough with its left cheek in the groove, takes the plough by the handle in the right hand, resting, meanwhile, is left on the other end of the screw, screws up the right cheek, until the point of the knife just touches the book, then begins to push the plough along the groove backwards and forwards, turning the screw a little every time the plough travels from him. The knife, by this method, gradually passes over and through the entire edge of the book, removing, in a series of shavings, the surplus portion of it that projects above the level of the press. There are various minutise which will be described particularly when we come to the section accorded to ” cutting edges,” the foregoing brief description being only intended to elucidate the uses of the press and plough. Plough-knives must be kept very sharp, and require some care in grinding. They are kept in two principal forms, the common knife, shown at Fig. 5 (C), and the Scotch, or sliding, at Fig. 5 (D). The first has a square hole in its butt, through which the plough screw passes, as shown at E (Fig. S), while the Scotch knife has beveled edges, and the end of the plough screw has a channel, G (Fig. 5), formed in it, in which the knife slides, as shown at F (Fig. 5). Either knife is good, but our personal option is for the ordinary form, which, moreover, takes less grinding than the sliding one. The press can be had in various sizes, at different prices. The amateur will not require the largest size, and may get one to suit him, with plough and pin complete, at from 30s. to £2 2s. These two tools the amateur must have.

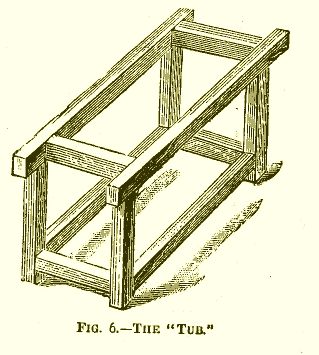

The ” tub ” (Fig. 6) is a rectangular wooden frame, upon which the laying-press rests, whichever side is in use. The ancient bookbinders used a veritable tub for the purpose, hence the present name. This should be strongly morticed and tenoned together, and can be made by any local joiner,or by the amateur himself, if handy with carpenter’s tools. It is best to put a bottom to it and board up the sides for 1ft. 6in. or 2ft., to keep THE TUB. the shavings in. The stuff of an egg-box or two is very suitable for this purpose. We must here mention that in a large establishment the cutting of edges, “out of boards,” is seldom done with the plough, but is accomplished by the ” guillotine cutting-machine,” in which, by lever power, a horizontal knife is brought forcibly down, and will pass through a pile of books at one stroke. As the machine is expensive, and not at all in the amateur’s line, we merely allude to it to render our list of tools complete.

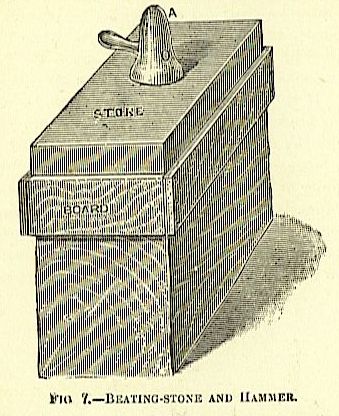

A “beating-stone” and hammer (Fig. 7) are indispensable. The hammer may be either of wrought or cast iron, something in the form shown at A (Fig. 7), with edges well rounded off and provided with a short wooden handle. It may weigh from 10lb. to 14lb. Any smith can make one. The “beating-stone” (Fig. 7) is a piece of York or Portland stone, or any stone capable of taking a smooth surface, about 2ft. by 2ft. or 1ft. 6in., and 2in. thick, ground upon its upper surface quite level. It should be firmly fixed on an upright support of wood, which should be a stout square log, firmly secured to the floor, or let into the ground, and covered on the top with saddle-cloth, felt, or several sheets of brown paper, to hinder, as far as possible, shocks or jars through the impact of the heavy beating-hammer.

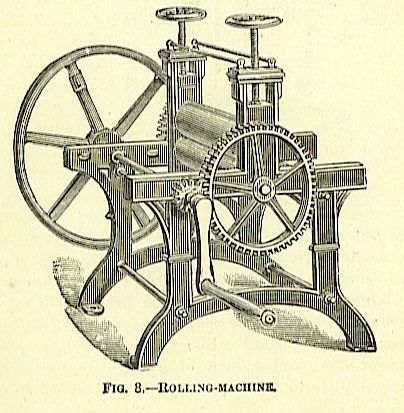

Beating-hammers vary in price from about 5s. The stone can be bought for a few pence; but the fitting of it up will depend upon the local charges for carpenters’ work. In all extensive bookbinding establishments the ” beating ” is now superseded by passing the books between the heavy rollers of the rolling-machine (Fig. 8), which was invented about fifty years since. If the amateur resides in a town, he can generally discover some binder who ” rolls for the trade,” and will pass his books through the machine at about an average of 1in. per vol., unless very large or thick; in this case he will not need the beating-hammer or stone. The rolling-machine costs about £30, and is consequently out of the question as an amateur’s tool.

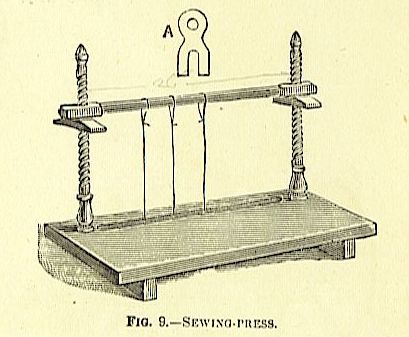

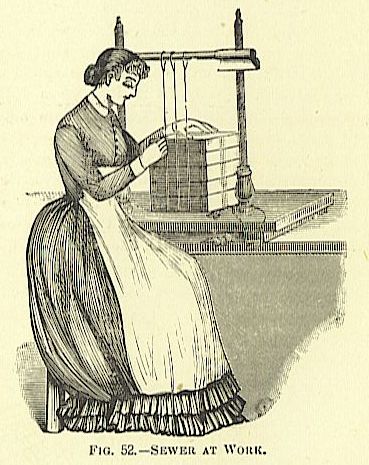

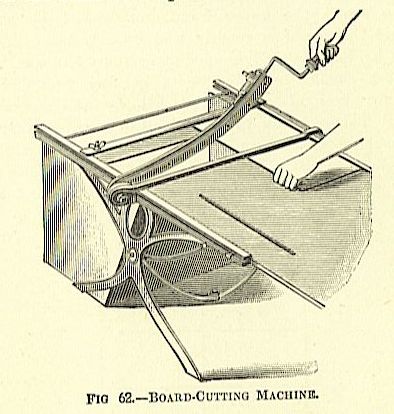

A small but important implement is the sewing-press (Fig. 9), which consists of a flat wooden bottom, provided with a vertical wooden screw at each end. On each of these screws revolves a wooden nut, and these sustain the crossbar, from which depend the cords upon which the books are sewn. These cords are secured beneath the bottom of the press by brass keys of the form shown at A (Fig. 9), of which five form a set. Middle-sized press and keys can be purchased for about 10s. 6d. A pair of medium-sized millboard-shears are necessary. These cost about 25s., and consist of a large pair of iron shears, precisely similar to those used by the whitesmith to cut up tin plate and zinc. They are screwed up in the laying-press or fixed, in a hole in the work-bench, and are used for cutting up the millboard covers for the books; though they are now almost superseded in establishments of any pretensions by the millboard-cutting machine, which consists essentially of a single large blade, worked by the right hand, and sundry arrangements by which any number of boards can be cut to one gauge (when fixed) without marking off.

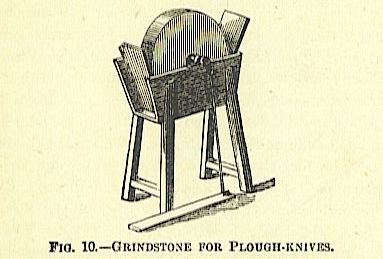

There are various other machines used in large establishments, to which we need do no more than allude, as in small places,, where great speed is a secondary condition, their work is accomplished manually. Amongst these are Starr’s backing-machine, or some modification of the original patent. This consists of two iron vice jaws, between which the back of the book can be ked, when a small iron roller is worked across it to produce the proper curvature. The bookbinder’s saw-bench, worked either by foot or steam, consists of several small saws arranged on a spindle, and is used for sawing the grooves to admit the cords in the back of a book instead of cutting them individually by the tenon saw. The bookbinder’s trimming-machine consists of a thin plate of steel something like a small circular saw, but quite sharp instead of toothed, usually driven by steam, and used to trim off rough edges and overplus of monthly magazines, &c., while still not removing sufficient to leave a smooth surface, as is done by the guillotine. A small grindstone for grinding plough-knives, &c. will be required.

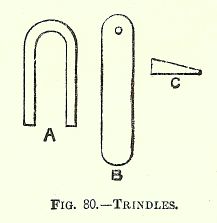

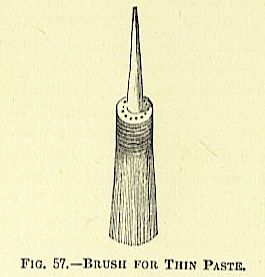

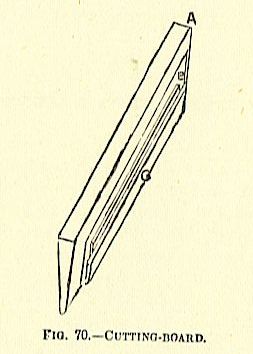

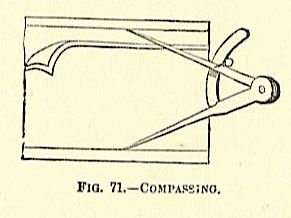

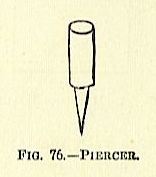

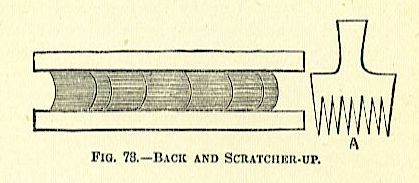

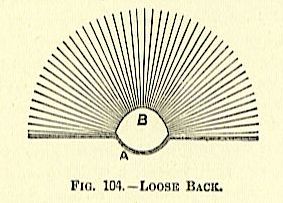

The form shown at Fig. 10 is a good one, and can be driven by the foot. A 2ft. stone, costing about 30s., will answer. We will now enumerate the minor forwarding tools. Two folding sticks (one pointed). These are pieces of flat bone, like small paper knives but without handles, 4d. and 6d. each; pair large scissors, long blades, for squaring plates, 4s. 6d.; small tenon-saw, 3s. 6d.; small wooden tub to hold thick paste, Is.; glazed earthenware pan to hold thin paste, 1s.; a glue-pot, 2s.; several small “sash tools,” as brushes for paste and glue, 6d. and 8d.; backing-hammer, 2s. 6d.; pair Lancashire wing compasses, 3s. 6d.; 9in. carpenter’s square, 3s. 6d.; knocking-down iron, 2s. 6d.; bookbinder’s rule, 4s. 6d.; scratcher-up, 1s.; oilstone hone, 2s.; shoemaker’s knife for cutting out, 8d.; French knife for paring leather, 2s.; pair band-nippers for setting bands nicely square, 3s. 6d.; pair trindles, 2s. 6d.; steel scraper for edges, 1s.; beech ” backing-boards,” per pair, according to size, from 4d. for 18mo to 2s. for imperial folio; beech “cutting-boards,” per pair, according to size, from 2d. for 18mo to Is. 2d. for folio; agate or bloodstone burnisher, from 4s. Gd.; pressing-tins, from 9d. each; pallet knife, 1s. 3d.; packet bookbinder’s needles, Is. The foregoing tools and machines can be obtained of the undernamed firms in London: Mr. Ullmer, Cross-street, Farringdon-road; Messrs. Harrild, Farringdon st.; Messrs. J. M. Powell & Son, 33A, Ludgate Hill; Messrs. Hughes and Kimber, West Harding-street, Fetter-lane, E.G.; and most printers’ brokers. Having briefly enumerated the tools requisite for ” forwarding ” a book, let us now advert to those which appertain to the ” finishing ” department. In trade technical parlance, “forwarding” comprehends all the operations up to and including getting the book covered with leather or cloth; and ” finishing ” is the affixing the gilt or other ornaments, and lettering the title on the back or sides. When space can be spared, the finishing is best carried on, not in the forwarding shop, but in a separate room, which should be well lighted. Here everything should be kept as clean and free from dust as possible, in order that the work in hand shall stand no chance of getting soiled. The necessary tools and appliances for finishing are neither numerous nor expensive, and the amateur would do wall to obtain those named in the following pages.

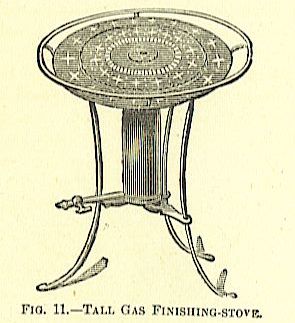

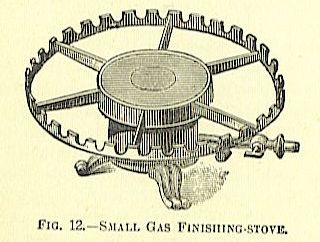

A small gas stove for healing the tools and letters, as illustrated at Figs. 11 or 12. The tall one, which stands on the floor on tripod legs (Fig. 11), costs about £2 10s.; the small one, shown at Fig. 12, which stands on the bench, costs 16s.

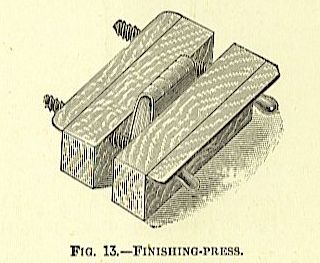

Both stoves are connected with the gas by an elastic tube. A stout bench, for finishing-press, &c., to stand on, is useful Some bookbinders do all their finishing at the ordinary laying, press; but the use of a finishing-press, which can be moved about on a shop bench, is much more convenient. The cost of bench would depend upon carpenter’s charges in vicinity; but a strong large kitchen table without leaves makes a very good substitute. A useful sized finishing-press, such as is illustrated at Fig. 13, costs about 12s. 6d.

It consists of a couple of small but solid beech cheeks, connected by a wooden screw at each end; the right end of each screw is turned up to a handle for the right hand, for in screwing up the book about to be finished in this press the hands only are used, a press-pin not being required. Larger sizes can be had. The screws should be occasionally lubricated with blacklead and soft soap.

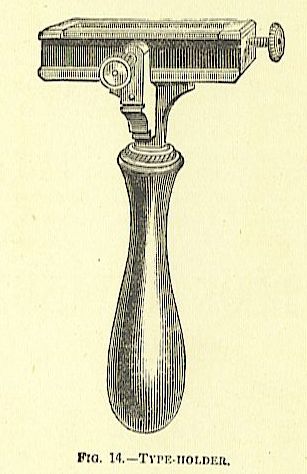

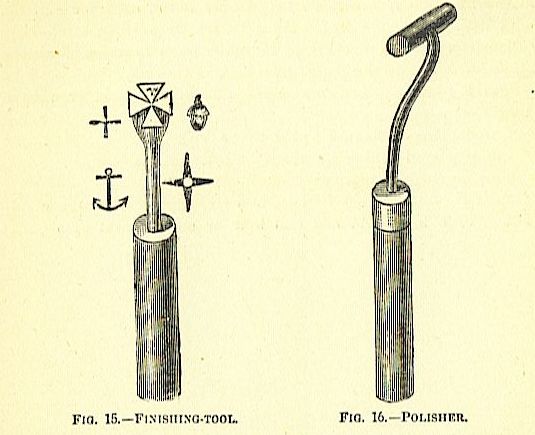

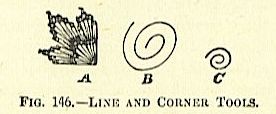

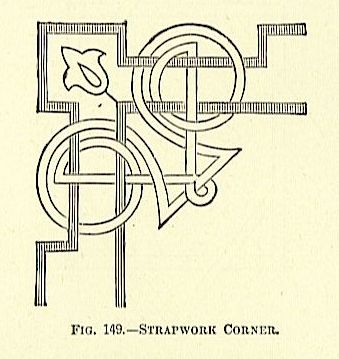

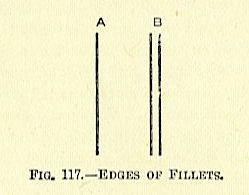

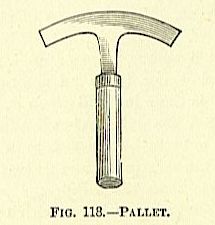

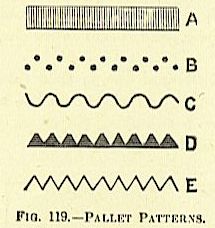

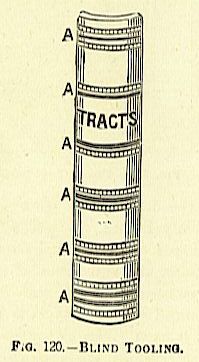

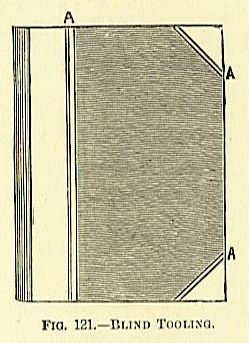

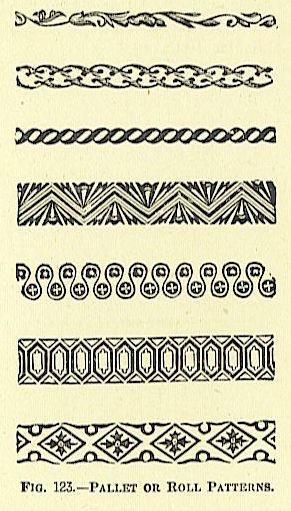

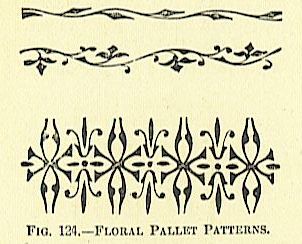

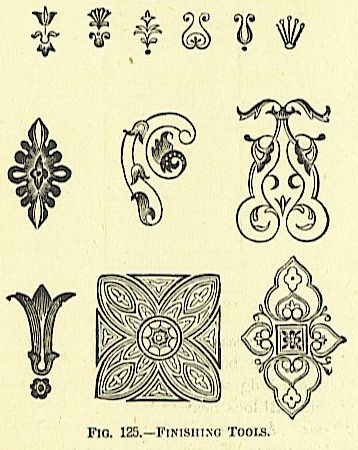

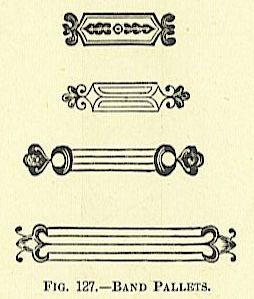

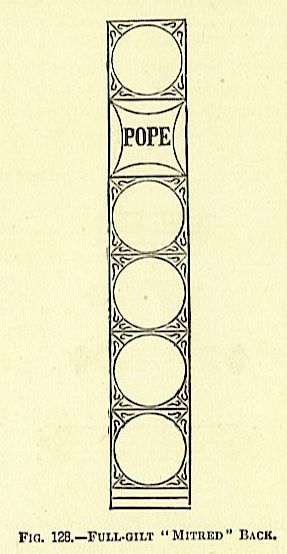

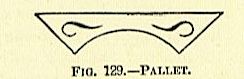

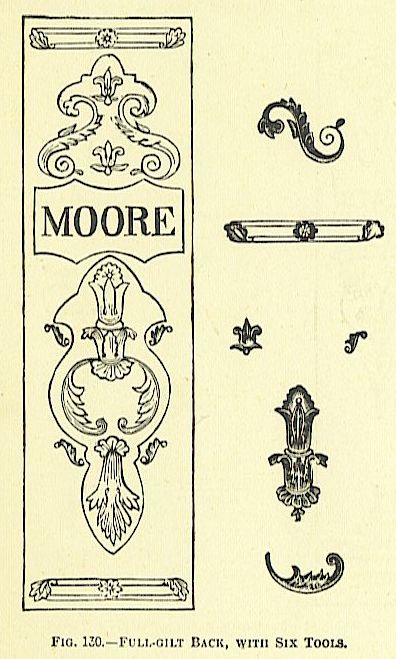

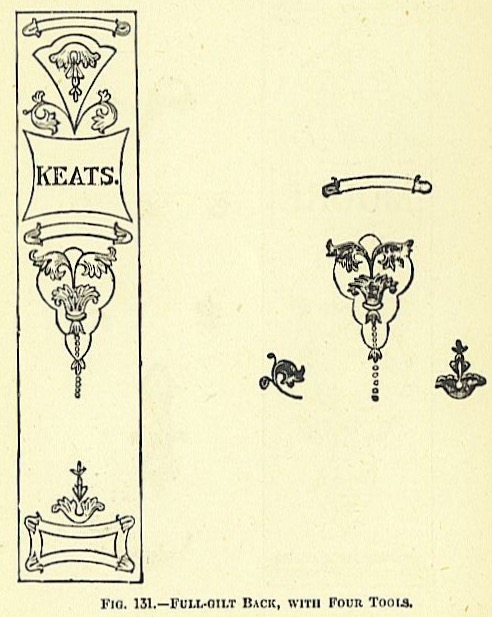

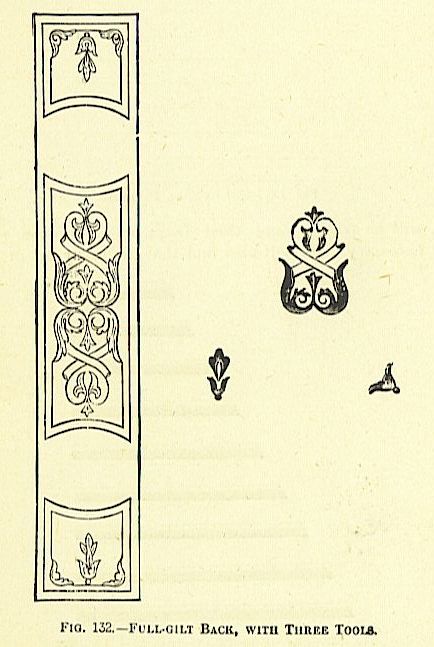

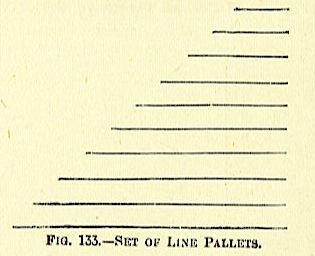

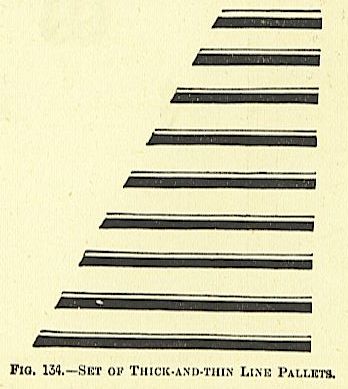

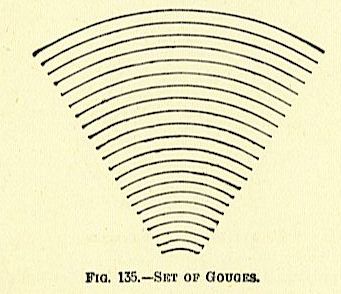

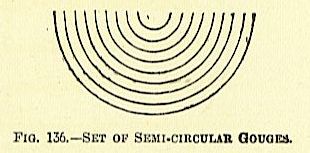

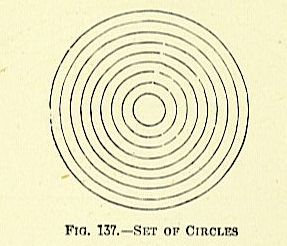

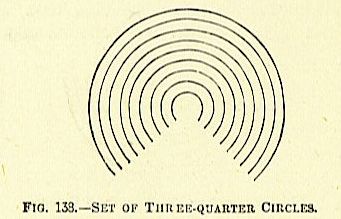

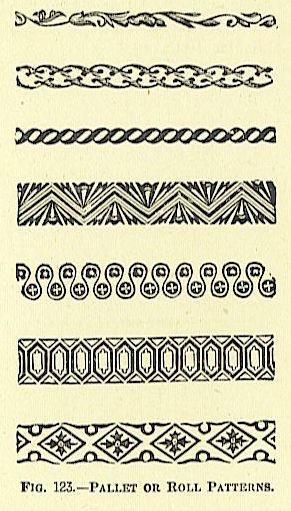

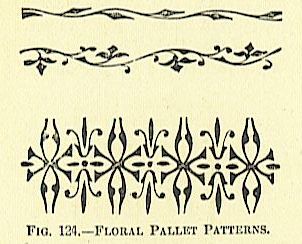

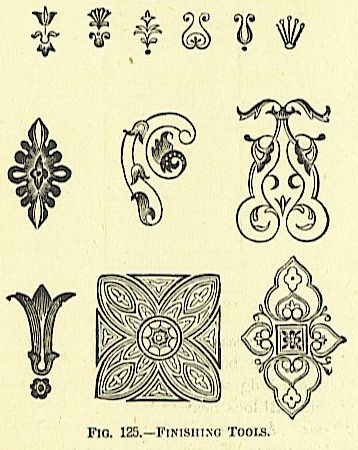

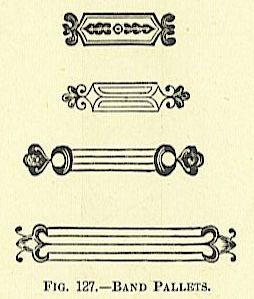

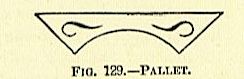

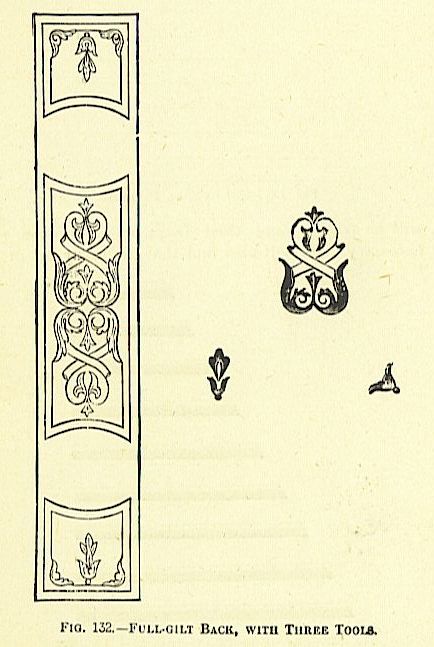

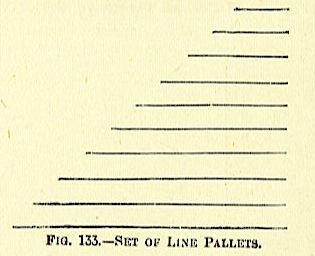

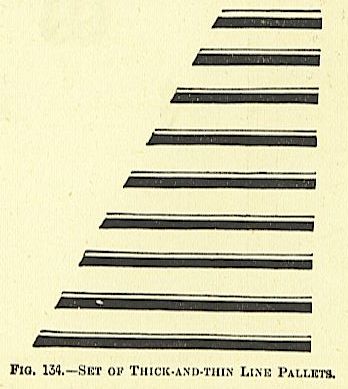

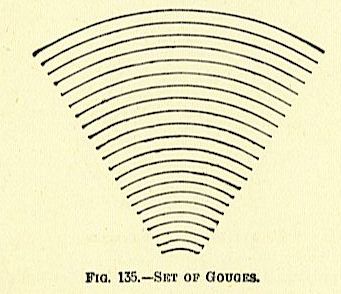

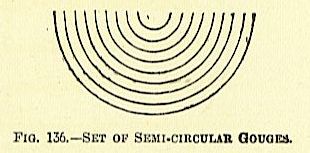

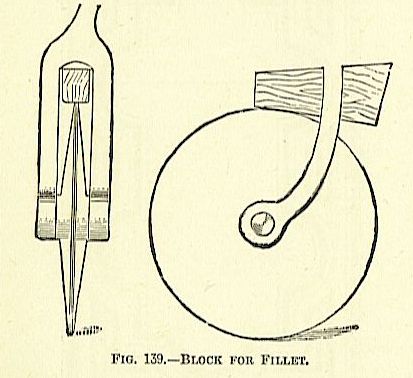

A single line, a two line, and a three line fillet are also required by the bookbinder. These tools are small brass wheels, the peripheries of which have been turned up to one, two, or three fine lines. Their use will be explained when we come to the department of ” Finishing.” It is sufficient here to say that when heated, rolled on gold leaf, and applied to the back or sides of the book, they leave a gilded impression of one, two, or three lines respectively. Other kinds, either of plain line patterns or those which have their periphery, or rim, engraved with floral and other patterns, can be had, and the purchaser can consult his wants and means in adding to the three described above. The line fillets cost about 5s. each. More elaborate patterns run up to 10s. and 12s., or even more, according to intricacy of pattern. Pallets are very useful, and a few should be obtained. These are small brass tools, about 4in. or 5in. long, and have line and ornamental patterns cut on their curved edge. They are worked across the back of the book, either with gold or without. (The latter process is termed “blind tooling.”) The binder should also have several alphabets of letters and figures and a brass case. Formerly the letters used in bookbinding were cut individually on the end of a small piece of brass, which was provided with a wooden handle, as shown in Fig. 15. Great dexterity was needed to properly “letter” the title of a book with these separate letters, and this undoubtedly led the bookbinder to use brass type, which he ” sets up,” as a printer might do, in the case shown in Fig. 14. These brass types are now sold in complete ” founts,” or sets of sufficient alphabets and figures for any ordinary works. The amateur can get price lists and specimens of the cast brass type of Messrs. Ullmer, Harrild, Powell, or any other dealer. The price runs from 12s. per 100 letters upwards for types. Separate handled letters run from about 10s. to 30s. per set of one alphabet and ten figures. In the specimens given the smallest size is suitable for 12mo and crown 8vo (these terms will be duly explained) volumes; the next size larger, for demy 8vo; and the largest for folio.

BOOKBINDING BOOKBINDING BOOKBINDING

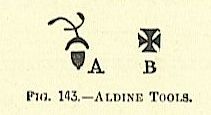

These three alphabets should be nearly sufficient for an amateur. Some binders employ ordinary printing type (of type metal, which is principally composed of lead); but this, although cheap, is so easily melted that we cannot recommend it to the amateur. The “cases” or “type holders” (Fig. 14) are 10s. 6d. or 12s. 6d. each. We may mention that many of the best binders, both in London and the provinces, do not adopt this plan, although decidedly the easier, but prefer to use the separate handled letters, under the impression that this expedites the work. An alphabet of these, suitable in size for the work in hand, is ranged round the top of the gas stove (Fig. 12), the handles resting in the recesses; and the finisher catches up each letter from its place as he requires it, brightens its face, presses it on its place on the back of the book, and replaces it on the stove. It need scarcely be said that it requires a very keen eye and steady hand to ” work” a line of small separate letters straight across the curved back of a large volume. In order to do this more certainly, some binders lay a small piece of sewing silk across the gold in a straight line, as a guide in working the separate letters. A selection of various separate ” tools,” of small pieces of brass (handled), on the ends of which are cut different ornamental devices–as Maltese and other crosses, acorns, anchors, &c. –used in finishing, will also be found useful. The price ranges from 2s. upwards, according to size and intricacy of design (Fig. 15).

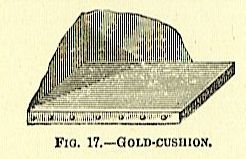

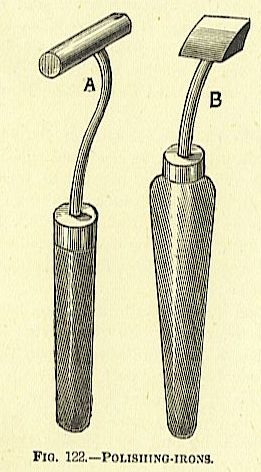

Amongst the minor but necessary tools and appliances are the following: A polishing-iron (Fig. 16). Used to give increased smoothness or gloss to calf books. Price 10s. Pressing-tins and boards for the final pressing. Gold-cushion. A piece of fin. board, covered first with a couple of thicknesses of flannel or cloth, and then with calf leather, with the “flesh” (rough inside) side uppermost, and with a piece of vellum sticking up from one end and part of one side as a guard (Fig. 17).

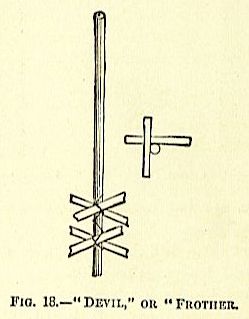

This can be made by the binder. If purchased it will cost 2s. 6d. Gold-knife. A small, straight-edged knife, used for cutting and lifting the gold leaf. Price Is. 6d. or 2s. Gilder’s tip. A few fibres of sable, fixed between a couple of cards. Used for lifting gold leaf. Costs 6d. Three small sponges, about the size of a peach, or rather larger. Small piece of flannel to oil books with. Small glazed pipkin in which to boil size, Is. Two or three gallipots. ” Devil,” or ” frother.”

This is a slight piece of tough wood, about 10in. long. At one end four or more pieces of a quill,cut about 3in. long and split, are tied tightly to the wood at right angles, as shown at Fig. 18. This is used to froth up the ” glaire,” as will be explained in a subsequent section. The little wire ” egg-whiskers,” sold at American Novelty Stores in London, answer excellently. Gold-rag. A piece of coarse canvas, well greased, for clearing off the gold first.

MATERIALS.

THE materials brought into requisition in the binding of books are not very numerous, and the following may be taken as being all that will be required by the amateur, or even the professional bookbinder; unless the latter be in a very large way of business, when crocodile skin and other novel coverings are sometimes called for:

Morocco and Calf.

These leathers can be had in different colours, from about 7s. per skin upwards. Calf is a smooth leather, morocco one with a raised grain. One is the skin of the animal whose name it bears, the other that of the Oriental goat. Either is excellent leather for good books, although morocco is just now, perhaps, the favourite. At Messrs. Eadie’s, Great Queen-street, Long Acre, either may be bought in half and quarter skins, or even enough for the back and corners of a single volume of course, at slightly enhanced prices over the whole skin relatively.

Persian.

We have said that morocco (Turkish understood) is the skin of the goat. Persian is also the skin of a small Eastern goat, but the leather is much harder and inferior to the Turkish. It is good leather, however, and very suitable to second-class work, and is only 3s. 6d. per skin. It may be had in various ” grains ” or surface patterns, but not in many hues only, perhaps, plum-coloured and dark green. The “hard grain” Persian is the best.

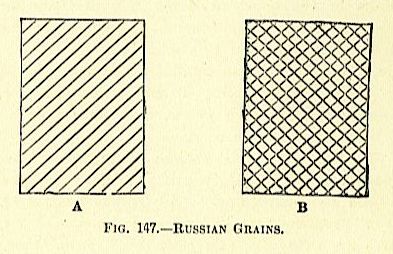

Russia.

This is a strong, brown, smooth leather, only used in ” stationery binding” i.e., for ledgers, pocket books, &c. It is occasionally used in bookbinding, and is a good leather, but very thick, and needs careful paring. It can be bought in skins or small pieces, but is expensive. It is celebrated for its pleasant odour, due to the empyreumatic oil of the Russian birch bark employed in tanning it. Hogskin.-This should never be used, as it engenders mildew and mould in other bindings placed near it.

Roan.

This is a stout sheepskin, tanned with, a smooth shiny surface and a straight grain. It is a common leather, but much used for half-bound books of no great value; about 4s. per skin. Skiver.-This is the “grain” or outside portion of a sheepskin, split from the “flesh” or inside of the skin (of which the so-called ” chamois” leather is made). Skiver is very thin, and will tear almost as readily as good paper. In appearance it is much like roan, but is only suited to very common work.

Vellum.

This is made from calfskin by a peculiar process. It is a tough but intractable material, much used in the Middle Ages, but rarely now, and then generally for ancient theological books. It resembles stout parchment. The skins are small, and cost from 5s. to 7s. 6d. or 10s., according to size. … , Velvet and Silk. These materials are occasionally used by bookbinders, but we should not recommend them to the amateur. Prices vary, and cannot well be quoted.

Bookbinder’s Cloth.

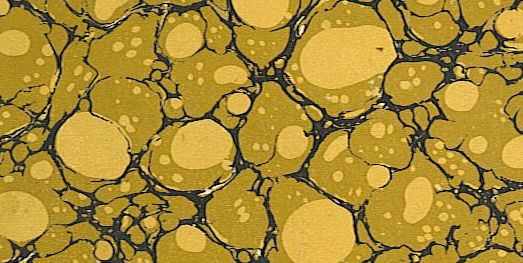

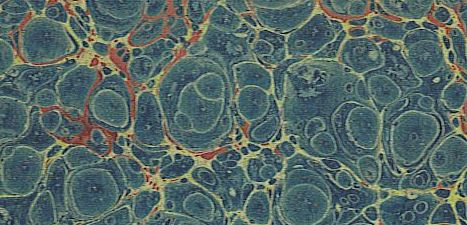

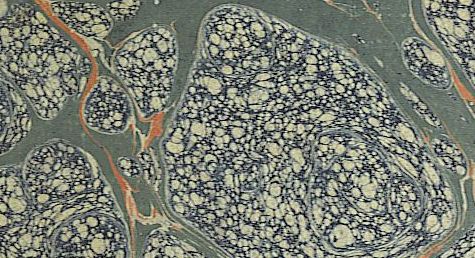

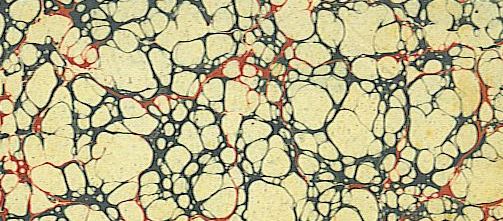

This is a textile fabric of about 30in. width usually, and sold in pieces of about 36yds., or can be bought for about Is. per yard; certain special colours, such as vermilion, scarlet, magenta, and mauve being dearei’, and some common colours, as purple, &c., cheaper. Cloth can be had in a large range of colours, and of ” grain,” which is a small surface pattern, produced by passing the fabric through engraved rollers. Some grains, such as morocco, are old; others, such as pin-head, new. Cloth is much used to cover the sides of half-bound books. Marble Paper.-This is used for end-papers and book sides. In such cases the edges are marbled to match. Coloured papers, of various tints, such as the brown Cobb so called from a bookbinder of that name are used for end-papers. Marbled paper, 2s. 6d. or 3s. per quire; Cobb and coloured paper, 7d. and 9d. per quire. Millboard is a hard board made from old rope. It is of different thicknesses, from “tip,” which is not much thicker than brown paper, to boards 1/4in. thick – more used by portmanteau makers. It costs about 44s. per cwt., good quality, but commoner kinds are cheaper. Strawboard is a common imitation of, and substitute for, millboard. It is very brittle, and only suited for common work. About 20s. per cwt. Headbands, ready-made, per yard, according to size and quality.

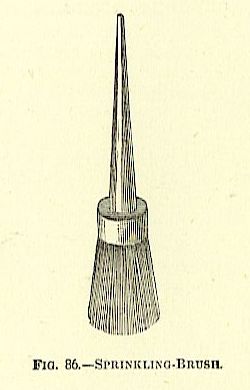

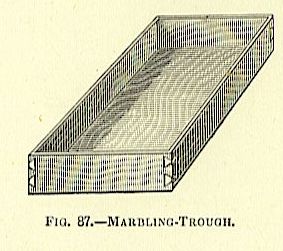

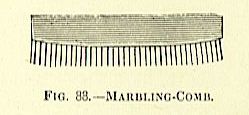

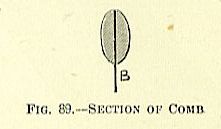

Stout Brown Paper for lining up the back of book. Glue, of good quality, 9d. or lOd. per Ib.; cheaper by the cwt. Paste, thick and thin. Gold Leaf, in books of twenty-five leaves, about 5s. per 100 leaves. Gold leaf varies in colour, some being ” deep,” or of a reddish hue, while ” lemon” gold has a silvery lustre. Deep gold is preferred by most binders. Parchment Shavings or Chippings, for size, may be bought by the pound, of account-book makers, &c. Glaire is the beaten-up whites of eggs. Bole Armenian, for making sprinkle for edges. Other materials for sprinkling and marbling colours are used, but if the binder intend to attempt the marbling of his edges himself, he will also require a marble slab and muller, a marbling trough, and sundry “combs;” also “flea-seed,” or gum traga-canth, and colours, as lake, indigo, orange, yellow, white, Chinese blue, black, green, and vermilion. These he can buy dry of any colourman, but his best plan will be to procure them in small jars (pounds), ready ground and prepared, of Mr. Corfield, dealer in bookbinders’ materials, St. Bride’s-street, London, E.G. Though we shall, in its proper place, give a detailed account of the operation of marbling, we would dissuade the small binder from attempting the process. It is both dirty and difficult, and a man needs to be in constant practice to insure success. If he cannot be satisfied with gilt edges for valuable books, and sprinkled edges for common ones, he had better keep the books by him until he can send them to one of the London marblers, who, for Id. or lid. per volume, will marble them as they should be, and return them promptly. Either the Mr. Corfield just mentioned, or Messrs. Eadie, of Great Queen-street, Long Acre, can be depended upon for this pur-pose. Either of these two old-established firms will also supply the binder with all or any of the materials which we have enumerated, with the exception that Mr. Corfield does not keep leathers. Messrs. Eadie do, and will even cut sufficient for a single volume (to match), either in morocco or call’. Most of the dealers in bookbinders’ machines and tools also keep materials.

Folding

FOLDING

WE now come to the first step in the actual process of Bookbinding, viz., that of folding or re-folding; the first term applying to new work, the second to re-bound books. In new work, the binder receives the sheets of the book from the printer flat, and not folded, and his first duty is to fold them so as to bring the pages into order, with proper margins of plain paper all round.

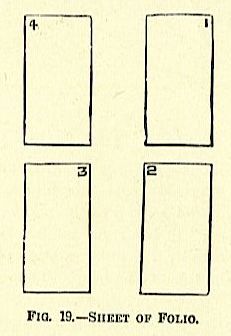

The manner of doing this will depend upon the number of pages in each sheet, and the manner in which the printer arranges (technically, ” imposes”) them. In the first place, if we take a sheet of white paper, of any size, and desire to have it occupied by four large pages. the printer will so arrange them that when the sheet is printed there will be the impression of two pages on each side of the sheet, as at Fig. 19 (this shows both sides of pages). Thus, one side will bear pages 1 and 4, and the other pages 2 and 3. This size is termed ” folio,” from the Latin word folium, a. leaf, and consists of two leaves only. Yery many of the ancient books were folio, as the size was convenient to the printer. This sheet only requires folding up the back, in such sort that pages 2 and 3 fall accurately on each other. To do this, a clean millboard is laid on the work-bench, and a pile of first sheets (or, as a binder would say, of ” section B”) is laid upon it with the inner pages upwai’ds, and the ” head ” on top of the pages farthest from the folder, page 2 being to his or her left hand, and page 3 to the right.

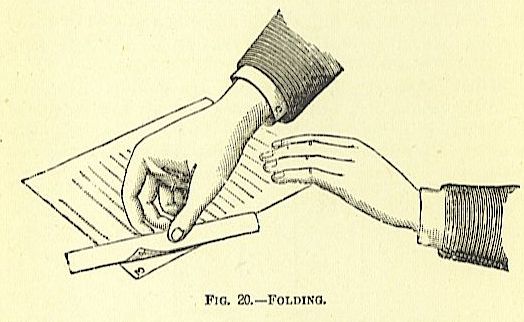

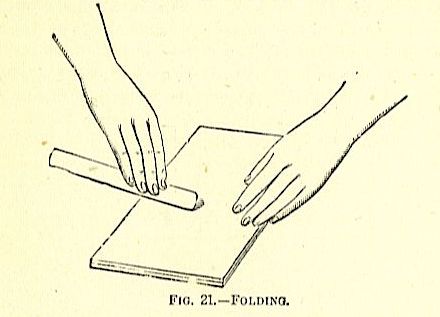

The folder holds a bone ” folding-stick ” in his right hand. He slightly “fans” out the heap of sheets by a circular motion of his folding-stick or thumb nail on the top of the heap. This permits the respective sheets to be seized expeditiously. The folder now, with his right hand, turns the right-hand portion of the top sheet (pages 1 and 4) over on to the left (pages 2 and 3), slightly doubling over the head of the page where the head-line and page figure are (as at Fig. 20), bending it a little over the folding-stick. He then advances the folding-stick and paper with his right hand until he sees that he has got the head-line and page figure of page 3 exactly on, and over, those of page 2. When this is achieved, he gives the folding-stick a rapid sweep clown the centre of the doubled-over part (page 4), from head to tail, .

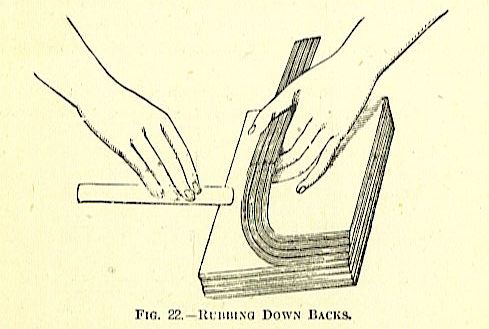

as at Fig. 21, and the sheet is folded. The sheet is now cut into halves, and doubled again up the back. It is then placed on the left, and a second sheet proceeded with. When all are finished, it is well to put the thumb of the left hand at the bottom of the back of the heap, and let the sections pass down severally, meanwhile working the edge of the folder along the back, as shown at Fig. 22. .

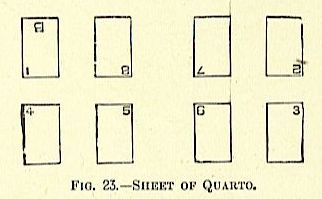

This presses the back fold close and tight, The next size to “folio” is the “quarto,” from the Latin word quartus, meaning ” four.” In this case, the printers put eight pages in a sheet, four on each side (as shown at Fig. 23).

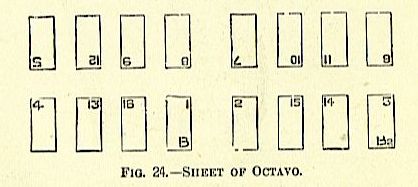

This, of course, necessitates an extra fold. After the sheet is folded as in folio, it is turned with the fold away from the operator, and the right – hand side is brought over the left. Thus, pages 3 and 6 are brought down on pages 2 and 7, and the fii-st fold made. The partly-folded sheet is then turned to the second position, and page 5 is brought accurately upon page 4, and the second fold made. The quarto is also an old-fashioned shape, but still lingers amongst us for certain books, principally family Bibles, dictionaries, atlases, and encyclopaedias. The next size is the “octavo,” from the Latin word for ” eight,” of sixteen pages to the sheet, eight on each side .

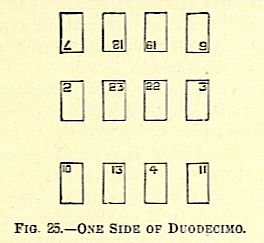

(Fig. 24). If the octavo were folded again, it would give small square pages of thirty-two to the sheet, called ” 16mo,” but this is such an awkward shape that it is very seldom used. Still another fold gives a “32mo.” This is not infrequently met with for very small books. The next legitimate size to 8vo (or octavo) is ” duodecimo,” or ” 12mo,” with twenty-four pages to the sheet (Fig. 25). It will be seen that the principle of dividing the sheet is different from that before noticed. Here the third part of the sheet, with eight pages, is so arranged that it has to be folded down upon the other part of the sheet before the main fold of the sheet is made.

Let us now describe the folding. In folding the 8vo, the sheets are laid upon the bench, with the signature (which will be seen at the bottom of the first page) turned to the top of the table at the corner nearest to the left hand of the folder, and presents pages 2, 15, 14, 3, below, and above, with their heads reversed, pages 7, 10, 11, 6, reading from left to right. The sheet is then taken with the left hand by the angle to the right and creased with the folding-stick in the right hand, in the direction of the two point-holes made in the printing, taking care, by shading to the light, that the figures of the pages fall exactly one on another, which will be 3 upon 2, and 6 upon 7, and thereby presenting uppermost pages 4 and 13, aim above 5 and 12. The top part of the sheet is then brought down, with the left hand, upon the lower pages, 5 and 12, falling upon 4 and 13, directed properly, and again folded. The sheet then presents pages 8 and 9, which are then folded evenly, 9 upon 8, forming the third fold, finishing the sheet. In folding the 12mo (Fig. 25), the signatures, when placed before the folder, should be at the top at his left hand, and towards the table, the sheet presenting pages 2, 7, 11, 23,18, 14, 22, 19, 15, 3, 6, 10. On the right, pages 11, 14, 15, 10, are separated from the others by a large space, indicating that they should be cut off. The folder detaches this part with the folding-stick, and, bringing page 11 upon 10, makes a fold, and 13 upon 12, which will be uppermost, finishes the folding of what is termed the “inset,” which bears the signature of the sheet it has been separated from, with the addition of a figure or asterisk, as A 5 or A*. The remaining eight pages are folded in the same way as the 8vo, and, when done, the inset is placed in the centre of them, taking care that the headlines of both range correctly.

Books are sometimes printed in what are called ” half-sheets,” but they are folded the same, after being cut up. The next size (still diminishing) is octodecimo, or 18mo, with thirty-six pages to the sheet. There are a few books (principally Prayer-boots and devotional manuals) which are still smaller (48mo and less), but these do not come much in the way of the ordinary bookbinder. It must be understood that each of the preceding denominations and sizes applies to all sized sheets of paper, and hence the total number of book sizes is greatly enlarged. For example, demy (a sheet of which measures 21 1/4in. by 19 1/4in.) may be termed the usual or standard size of paper. Demy 8vo measures about 9 1/2in. by 5 1/2in., and is a very usual size for modern books.

All the reviews, and most of the magazines, are of this size. But there are also larger 8vos. Thus, the Leisure Hour, of the Tract Society, is an imperial 8vo, and much larger; Chambers’s Journal is a super-royal 8vo, aud also larger; while All ihe fear Round is a royal 8vo, only a trifle larger superficially than the demy Svo. The most important of the smaller-sized sheets is “post” or “crown.” The 8vo of this paper is much used, both in this country and abroad, for popular handbooks. “Crown” (or “post”) Svo is 4 1/4in. by 7in. per page, is a very popular and useful size, and is much used for novels and the generality of cheap French works.

Supposing the book to be bound is a volume consisting of monthly parts, you first see that they are in correct order, then take the wrappers off; next, go through them again, cut the thread that holds each part together, pull off the advertisement pages, take off the plates (illustrations), if any, and lay them, face downwards, in a pile in the order in which you remove them; and, lastly, pull all the ” sections” (sheets) of which the part is made up, apart, and lay them down in order, face downwards, proceeding thus through all the parts. The title-page and contents will usually be found at the end of the last part, and these must be placed at the beginning, before section B. When folding, you turn the pile of separated sections, with the title-page upward, and place them on your left hand. You then take up the first section (the title-page), and having cleaned off any glue which may have adhered to the back, by rubbing the edge of the folding-stick up and down it, from head to tail, a few times as it lies on the millboard, next, with the same tool, unturn any dog-eared corners, giving them afterwards a pinch with the thumb and forefinger of the right hand to make them retain their proper position; and, lastly, observe whether the sheet has been rightly folded, so that the lines of the title run straight across the page; if not, you alter their position and give the back a fresh crease with the folder. You then put this sheet down, face downward, 011 your left hand, and, taking up section B, proceed to treat it in a similar manner. If the section is thick and has been badly folded, you will often find it necessary to divide it into portions of four leaves each, and fold them separately, afterwards re-inserting them in each other, taking care that all the head-lines and pages fall upon each other, which can be seen by holding the opened section up to the light.

It will not unfrequently be found that when the head-line* are thus got to agree, the margin of plain paper above them is much more to some pairs of leaves than others.

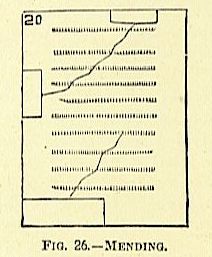

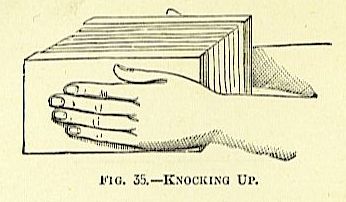

This must be obviated, or when the book is “knocked up” all the edges will come to correspond, and then the head-lines will get ” out of register” (or correspondence) again. When you have got the head-lines right, therefore, and discover any pairs of leaves that have less margin than they should have, the middle of the back of the pairs of leaves inside these should be touched with, a pasty finger, so that the tiny portion of paste left on it will hold the short pairs of leaves down, with the head-lines in the right place. Half the surplus head margin on the other pages should then be cut off with a pair of scissors. When the whole of the sections have been re-folded, turn the pile (which will be rather higgledy-piggledy) again in a pilo at your right hand, with the title-page upwards, and, taking from the top a parcel of about twenty sections, proceed to ” knock-up ” these, i.e., to tap their heads (top edges) and backs upon the millboard, until they are all quite level. “When this is done, lay the parcel on the left, face downwards, serve the next twenty sections in a similar way, and so on, till the whole volume is perfectly level at the head and back, when it may be put aside on a shelf for rolling or beating, which must not be attempted until any paste used is quite dry. If any of the leaves of the book are torn, they may be mended by pasting small pieces of plain white printing paper (such as is used for the end papers) across the margin (on each side of the page) where the tear crosses it, as shown at Fig. 26.

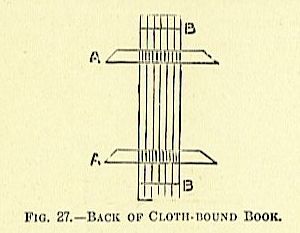

Some very dexterous menders can scrape away each of the edges of the tear with a sharp penknife, so that they resemble ?what carpenters call a ” scarf,” and cement them together with paste, so that no paper slips are required; but this skill is very rare, and only needed for valuable works. One of the menders employed by the celebrated Roger Payne was famoua for her dexterity at this work, and commanded high prices. Lastly, we come to the re-folding of books which have been previously bound. If these are cloth boarded, the two boards are first turned back, and held tightly in the left hand. The sections of the book are’now held in the right, and, by a sudden jerk, are forcibly torn away from the boards. It will now be found that the back of the book is covered by a piece of canvas and brown paper. This being pulled off, the back of the book will be exposed, as at Fig. 27. With a sharp knife, the tapes upon which the book is sewn (A, A), and the ” kettle,” or catch stitch, which secures the sewing (B, B), are now cut out, when the sections can be easily pulled apart. The glue is then cleared off, the thread taken out of the middle of each section, and any folding that may be required is effected. “With ” bound” books (those in leather) the procedure is nearly the same.

The boards are first removed, by cutting through the cords which secure them to the back. The leather and paper are then scraped off the back, the cords and kettle stitches cut out, and the sections pulled apart. Some old “tight back “books, sewn upon raised bands, may present trouble from the tenacity with which the lining of paper and the leather adheres. If very refractory, it will be well to plaster the whole back over with thin paste, leave it to soak for an hour or two, lightly screw up the book in the laying press by its fore edge, and then scrape off the softened leather and paper with a blunt knife. The back may then be rubbed clean and dry with a handful of shavings, the cords cut out, the sections taken apart while damp, and the other operations proceeded with as before.

PLACING PLATES, BEATING AND PRESSING BOOKS.

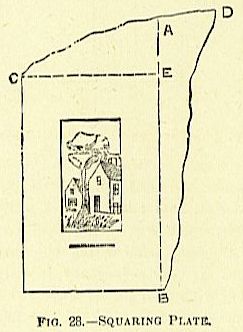

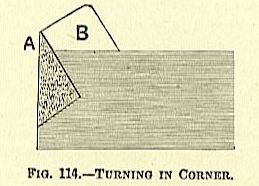

WHEN the books arc folded or refolded, as the case may be, the next step is to place the plates (if any) in their proper positions. To aid the binder, there is always a printed list of plates, attached to the contents. Guided by this, the binder finds the place, and, having ” squared ” the first plate, dips his forefinger in some thick paste, and pastes the back of the plate for about an eighth of an inch in, and then puts it in its place and rubs it down with the back of his finger. The ” squaring” consists in seeing that the margin of the plate at the back and head is uniform in quantity along the plate, or otherwise it would be out of the straight when the book is cut.

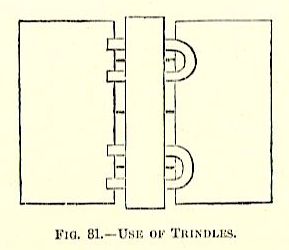

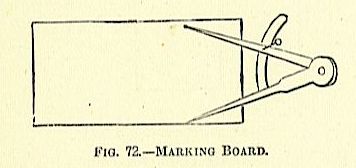

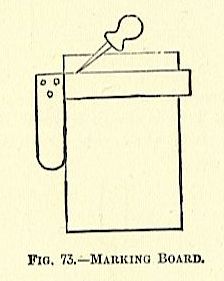

For instance, let Fig. 28 represent a plate printed on a piece of paper, of which the edges are represented by the black lines. It is obvious that, if it were pasted and fixed by the edge, B, D, it would be out of the square. Consequently, the binder cuts off the superfluous portion at the back along the dotted line B, A, and then makes another cut, at right angles with this, at the head, along the line E, C. This is generally done by eye with a pair of long-bladed scissors or shears, but sometimes the binder places the plate on a smooth cutting-board, and, placing a thin straight-edged board, called a ” trindle,” along the line he wishes to cut, draws a keen knife along the edge of the trindle, and then, trims the head in the same manner.

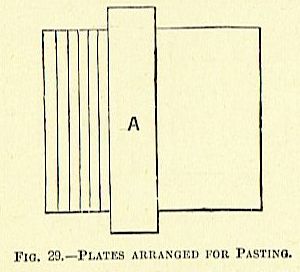

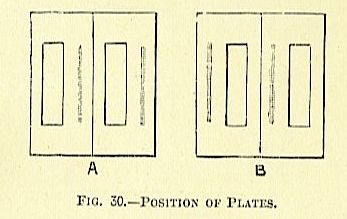

If the plates are numerous, he will sometimes, instead of pasting each separately as he squares it, square a number, and then lay them down on a board one over the other, leaving about an eighth of an inch of the back of each uncovered, as at Fig. 29, then place a board, A, over the top one, and, holding this down firmly with the fingers of his left hand, draw the paste-brush over all the exposed edges. It must be borne in mind that the plate must always be pasted at a back (behind the side of the printing) edge; also that plates printed the long way of the paper must always be so fixed that the ” inscription” line or title of the plate must be on the right hand of the page, as at A (Fig. 30), never reversed, as at B (in same figure).

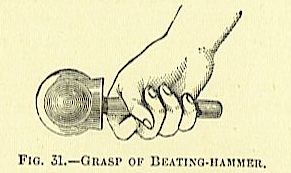

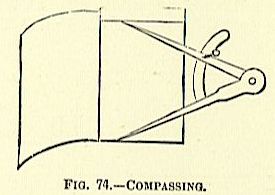

This is done in order that when the book is inspected the reader shall not have to reverse it in looking at such plates, and is de rigueur. In books consisting wholly of plates on plate paper, it is far best to square them with the boards, and, if folios, it is well to mark off the margin accurately with the compasses before cutting. Maps or doubled plates should be “mounted” by pasting a slip of stout cartridge paper up the fold, leaving about half an inch of the paper to paste to. Maps or plates should never be folded in several folds to get them in. This is a clumsy expedient, and, after the book has been used a little, the folds are sure to get out of order, and the fore edge of the maps, &c., to protrude, causing the book to ” gape ” and look most unsightly. When all pasted places are dry and hard, the books are ready for ” beating ” or ” rolling.” Beating the book with a heavy hammer is of great antiquity. In one of the quaint sketches which the Dutch designer, Jost Amman, has left us of contemporary trades, is one of a bookbinder at the operation of beating. Unlike the modern, who always stands at the stone, the operator is comfortably seated on a cushioned stool. Unlike, too, the bookbinder of the present day, his ancient prototype grasps his hammer as a smith might do, and, raising it above his head, brings it down with the full force of his muscular arm. We gave an illustration of the hammer in a previous chapter.

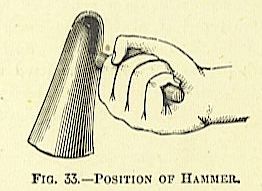

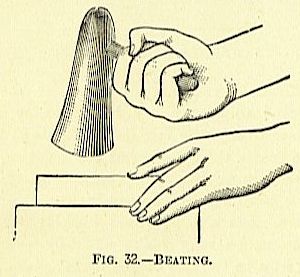

Let us now speak of the manner of holding it. As the hammer rests on the stone, the binder grasps its short handle firmly with his right hand in such a manner that his knuckles point to the stone, and his nails are upwards, the outer side of his forefinger resting against the inside of the head of the hammer (Fig. 31, as seen from above). The hand is then swung over from the wrist, so that the operator can see the face of the hammer (Figs. 32 and 33).

This peculiar action, with the back of the hand downwards, insures that the face of the hammer always descends perfectly flat, which is essential, or the paper would be cut or bruised.

The learner should practise on a packet of waste paper, and must not be disheartened if, at his first essays, the paper be full of hills and holes, and perhaps with half a dozen long sharp cuts through it, where he has permitted the edge of the hammer to fall first. As he acquires dexterity and his wrist gains strength, he will soon get the ” hang” of it and find iteasy enough. The book or paper is held by one corner with, the left hand, and moved about so that all its surface is successively brought under the action of the hammer. The operation is shown in side view at Fig. 32. The number of sections taken to a “beating” must be left to the discretion of the operator. If it is a re-bound book, care should be taken that the projection at the back of the section, where the former ” joint” has been, should be well levelled. Perhaps it will be safest for the tyro to go over this with the backing hammer. The number of strokes necessary for each ” beating ” must be left to the judgment of the workman. The work looks very laborious, but is really not so when the knack is acquired, for we can well remember that in our apprentice days we have often stood at the beating-stone for three or four hours at a stretch. A piece of plain waste paper or part cover should be placed oa each side of the beating, to preserve the first and last section from actual contact with the stone or the hammer. Before commencing to beat a book, the operator should refer to the date at the foot of the title-page, to ascertain when it was printed.

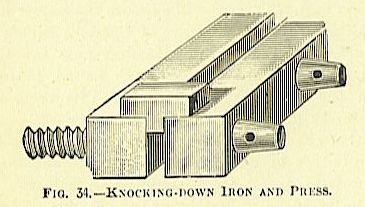

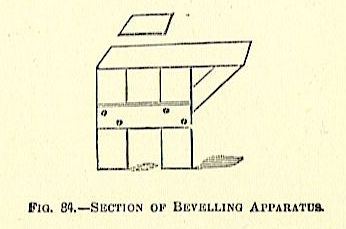

This is necessary, because, if recently-printed books are exposed to very heavy beating, they will probably “set-off”; that is to say, the ink lines will be partly impressed on the opposite pages, thus rendering the printing more or less illegible, and much impairing the appearance of the book. New books should be beaten very cautiously. If the amateur has not provided himself with a beating-hammer and stone, he may make shift by screwing up the knocking-down iron in the end of the laying press, as at Fig. 34, and beating his books thereon with the “backing hammer.”

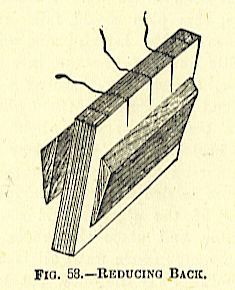

This is, of course, only a very inferior makeshift; still, the work may be done so. In all tolerably large establishments the rolling-machine has superseded the beating-hammer for many years past. Of this machine we have given an illustration. It consists essentially of two large smooth-surfaced iron cylinders, between which the books are passed; it is provided with an apparatus by which the rollers or cylinders can be brought together or set further apart; it does its work well and quickly. The operator sets the rollers at what he considers a suitable distance asunder, then takes a number of sections and places them between a pair of tin platea of corresponding size, and puts them to the rollers, while an assistant turns the handle.

The plates and sections are caught by the rollers and drawn between them, and are received by the assistant as they emerge at the other side. Precautions against ” setting-off ” are as necessary with the rolling-machine as with the beating-hammer. We may here remark that of late years a new kind of book illustration has come into vogue which needs special precautions. We allude to the “chromo” plates, such as those issued with the Leisure Hour, Sunday at Home, &c. The coloured inks and oil colours used in printing these are very slow in drying. This is especially the case with the dark brown used in the shadows (probably asphaltum), which seems as if it would never dry; and if such a plate were inserted in its place before the book were beaten or rolled, it would be found to have adhered to the opposite page so tenaciously that it would be impossible to separate them. These plates must, therefore, never be ” placed ” until the book has been through these operations; but this is not all. They will even ” stick ” from the other ordinary pressure the book will have to go through. It is, therefore, necessary that, after each plate is placed, the binder put a piece of waste paper in front of it, to guard against sticking; though, in all probability, when the book is bound, he will not be able to get even this waste paper off without the use of moisture, which is objectionable. Perhaps, proper-sized pieces of the ordinary oiled tracing paper would answer better, although we have not personally made the experiment.

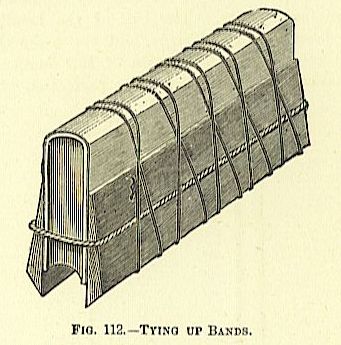

The whole of the ” batch ” of books which the binder has undertaken to ” forward ” together being now beaten or rolled, it is next usual to put them in the standing press and leave them there at least a night, to render them still more compact and level. “We have given an illustration of the common screw standing-press, and also of the Athol and Boomer presses. The manner of ” blocking up ” is similar in all. The binder is provided with a number of pressing-boards of all the various sizes, and he begins by dividing each volume into several parcels, and putting in the largest first. Thus we will suppose the binder has several volumes of the Graphic (folio), two of Cassell’s Bibles (4to), and twenty Quarterly Reviews (8vo). He first puts the Graphic in the folio boards, a board between each parcel, taking care to” place it in the centre, then cautiously lifts them on to the bed of the press and takes care they occupy the centre of it. This may be effected by measuring the distance from the ends of the boards to each cheek of the press, and making this uniform on both sides; then, standing outside the left-hand cheek of the press, he judges by eye if the pile of boards and books occupies a central position as aligned against the inside of the other cheek. This should be done very carefully. The binder now divides the Bibles into parcels and places them between a suitable number of quarto boards, then lifts these on to the folios already in the press, taking care that they stand in the centre of the uppermost folio board. Next the reviews are placed between octavo boards, and lifted in with similar precautions.

Now, upon the top octavo board is put an octavo pressing block, which is a piece of deal or pine, about Sin. thick, planed level and square. Then, while the blocker upholds the pile of books and boards steady and upright, an assistant lowers the “platen” or “follower” of the press by turning the screw. When he can cause it to revolve no longer, he takes out the wooden peg, and, putting in the shorter iron press-pin, pulla down as long as he can from right to left. When this pin will actuate the screw no longer, the long pin is substituted, and one man pulls while the other pushes, till all is done that their united strength can achieve, when the shorter pin is placed in one of the screw holes in such a manner that one extremity rests against the right-hand cheek.

This is done to prevent the screw from receding during the night, and consequently relaxing the pressure, which a well-oiled iron screw will not infrequently do. The binder should examine the pile of books with his eye frequently as the “pulling down” goes on, not only from the front, but also from the sides?indeed, most from the latter; for, if he has not blocked up the press truly perpendicularly, he may find his pile bend or bulge, and, as the pressure increases, presently shoot out pell-mell, either behind or before the press. It is not advisable that there should be too great disparity in the sizes of the books put into the press at one time. If it begins with folios, it is better to end with octavos, and reserve the smaller sizes for another blocking up, or even, if there are only two or three, screw them firmly up in the laying-press.

Sewing

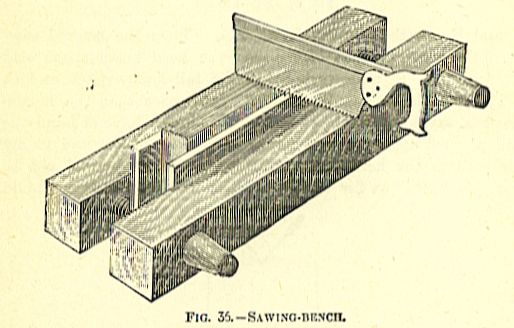

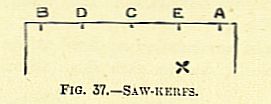

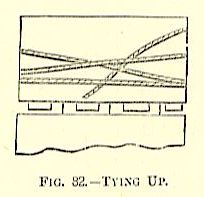

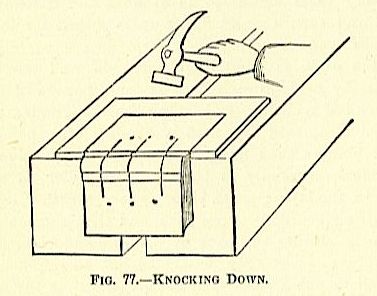

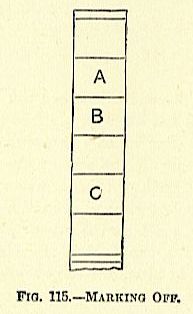

THE press-load of books should be left in the standing-press all night, and the next morning they will be ready for sewing. The press is unscrewed by pulling the press-pin round the contrary way, viz., from left to right, and the boards and books lifted out. The various portions of the books are then taken from between the boards and laid together in proper order, so as to form volumes. The next operation is to saw the backs for sewing. If the reader will examine an ancient book, say, one bound 100 or 150 years ago, he will find the cords (” bands,” they are called) upon which it is sewn project from the back. In process of time, however, this appearance of the bands came to be considered objectionable, and the adoption of the ” open back,” in place of the “tight back,” rendered them inconvenient, and “kerfs,” or channels were cut with a saw in the back of the book, to permit the bands to sink in. A ” tenon” saw is used for this purpose. It should be kept sharpened and properly set. Several books of the same size are laid together, say, four octavos (Quarterly Review], with their backs and heads together (level), and an octavo pressing-board is placed at each side of the parcel.

They are then lifted in both outspread hands, as at Fig. 35, and brought down forcibly on the right-hand cheek of the laying-press. This is done several times to both the back and the head until all the sections are beaten up level at both places. This is termed ” knocking-up.” It may here be well to remind the reader that the four edges of a book or a leaf are termed: The top, ” the head ” ; the front, the ” fore-edge “; the bottom, the ” tail” ; the other edge being, of course, the ” back.” When the books are knocked up level at the head and back, set the two boards, one on each side, about 1in. from the back, lower the fore-edges into the laying-press, and screw up with the hands.

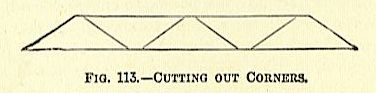

Stand at the side of the tub, so that you face the side of the press, and, taking the tenon saw in the right hand, make a cut (or ” kerf,” as the carpenters call it) across the back, about an inch from the head (as at Fig. 36). This is to receive the top “kettle-stitch” (or ” catch-stitch”), so will not require to be very deep, about the sixteenth of an inch, or rather more if you are going to sew the book with large thread. Next, make a corresponding kerf at about 1 1/2in. from the tail of the book. Then, supposing the book is an 8vo, with eight leaves to the section, measure with the end of the saw (as at X, Fig. 37) to find the centre between the two kettle – stitches. When found, make a saw-cut there. With a book of 8vo size, it is usual to sew ” two on” with good sized threads, so that three cords will be required; consequently, the distance between each of the kettle-stitches and the last cut made must be judged by eye, and another saw-kerf made between them.

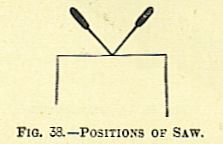

This process is shown at Fig. 37, where A and B are the two kettle-stitches. Then the central saw-kerf, 0, is made; then D, between the head kettle-stitch and C; and, last, E, midway between the tail kettle-stitch and 0. The three latter saw-kerfs should be deeper than the kettle-stitches, say, about 1/2in. It is a good plan to have at hand the ball of cord upon which the volume is to be sewn, and to lay the cord in the kerf. The form of the latter should not be a simple “cut,” as for the kettle-stitches; but the kerf should POSITIONS OF SAW be wider at the bottom. This is effected by slanting the saw first to one side and then to the other as the sawing goes on, as at Fig. 38. By this means the bottom of the kerf is enlarged; it must not be too big, however.

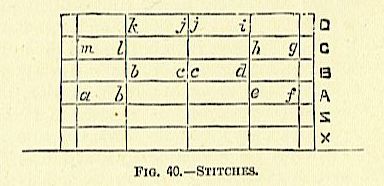

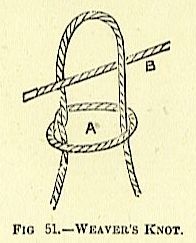

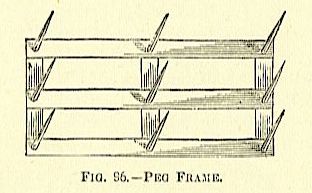

The size of the cord used for the hands depends upon that of the book; generally the warehouseman where you deal will sell you the usual size. The number of bands and saw-cuts depends upon the number of leaves to the section, as a rule. After the book is sawed, and before sewing, it should be “collated,” in order to verify that the sections are still in proper order. This is effected by holding the volume in the left hand by the angle of the back and head, the tail of the book being upwards; the whole of the sections held by the right hand are permitted to escape from the restraint of the right thumb, one by one, and to fall upon the left hand, the eye attending to the signature of each section as it falls over, and seeing that the sections follow in order, as ” Title, B, c, D,” &c. In order to get a nice round back to the book, when backing, there must be a certain amount of thread in the back, so as to spread it out sufficiently. On the other hand, if you get too much thread in the back, the book becomes unmanageable. As a general rule, small books (18mo and 12mo), with twelve or more leaves to the section, are sawed for two bands, and sewed all the length of each section with fine thread. Octavo, of whatever sized sheets, may be sawed for three cords, and sewed two sheets on, as follows: The first section (title – page) is laid on the bed of the sewing-press (which was illustrated at page 16, Fig. 9), with its back to the cords; the saw-marks are brought to the cords, and the cords are moved to the proper place, so that the latter enter them; the press is screwed up, so that the cords are tight. The needle (threaded) is now introduced in the tail kettle-stitch saw-cut, and brought out at the saw-cut D (Fig. 37); there it passes around the band (cord), and re-enters the section again at D, but on the other side of the band. It then passes along, inside the section, to kerf C (Fig. 37), where it emerges, and is re-inserted in the same saw-kerf, after having gone round the band; and so on, passing round each cord, until the needle finally emerges at the head kettle-stitch kerf, A (Fig. 37). The next section is then laid on, and the needle passed into the head kettle-stitch, A, and the same process of sewing round the cords repeated, only in reverse order, viz., from head to tail, instead of from tail to head. “When the thread comes out at the tail kettle-stitch of the second section, it is tied to the end of the needleful which is still projecting from the tail kettle-stitch kerf of the firat section sewed. It must be understood that the thread is not drawn entirely through or out.

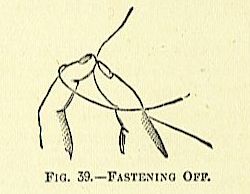

The usual way of making this knot is to throw the thread attached to the needle over and around the forefinger and thumb of the left hand, and then, with the finger and thumb, take hold of the end of thread which projects from the tail stitch of the previous section, gradually pulling the top of thread across the fingers, tight, with the right hand. (Fig. 39 gives some idea of the position.) This is the first kettle (catch) stitch, and these two sections have been sewn ” through,” i.e., they have thread all through their length.

Now we will begin to sew “two on.” We will place a third section on those just sewn, as A, Fig. 40, and, passing the needle in at the kettle-stitch a, let it emerge at the band kerf b. The fourth section, B, is now laid on, and the needle, having gone round the band, enters this at b, being on the other side of the cord to that at which it emerged at b from section A. The needle now passes to c, round the cord, and from c to d, along the middle of the inside of section B, coming out at d. Here it goes round the cord, and is then pushed into section A again at e, passing from e to f along the middle of the section, and coming out at f, where another kettle-stitch is made.

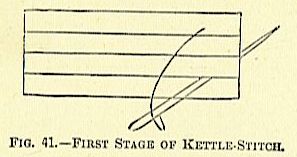

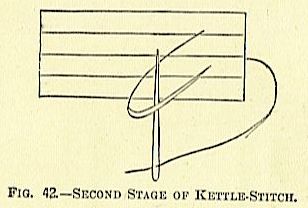

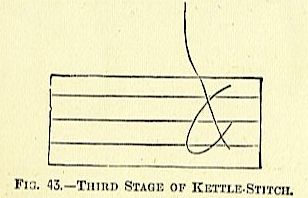

This is effected by passing the needle in between the two previously-connected sections from the back inwards, as at Fig. 41, so that it can come out between the section at the head, as shown. The needle is then passed upwards through the loop there made as at Fig. 42, and then drawn gradually up, as at Fig. 43, until it draws into a tight knot, which slips into the kerf of the kettle – stitch, so that it is below the surface of the back.

The previous process is then repeated (sewing towards the tail) with the next sections, C and D, the kettle-stitch being passed under the sheet last secured; and so on. In larger books, with still thinner sections (say four leaves to the section), it will be necessary to lay on more than two sheets in sewing, and, therefore, they must be sawed for more bands.

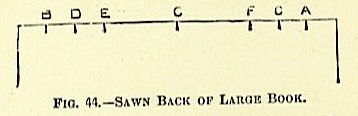

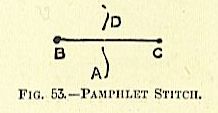

Thus, a, quarto, of four leaves to the section, should be sewed on five bands. In sawing this, the kerfs should be arranged at about the proportional distances of Fig. 44. sewing, three sections are laid on, thus: First section sewn from B (kettle-stitch) to D; second section from D to E, third section from E, around 0 to F.

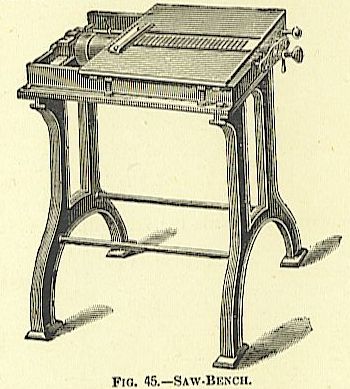

As this stitch has no hold at either end, it is made longer; then, going back to first section, it is sewn from F to G, and then the second one from Gr to A, the kettle-stitch securing the whole. In all cases, the first two and the last two sections of every volume should be sewn all the way along, as shown at Fig. 40. In large establishments it is common now to supersede the manual use of the tenon saw by the bookbinder’s saw-bench (Fig. 45).

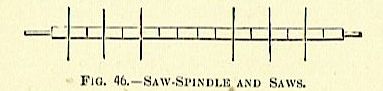

This machine, which is worked either by the foot or by steam power, is very useful. The saws (of which seven are supplied with the machine) are circular and small. They are arranged on the saw spindle by placing collars between them, so as to separate the saws as desired (Fig. 45). The washers will give a change for every quarter of an inch. Of course, this is only for new work. The top edges of the saws project through the slots in the plate, and the pile of books, well knocked up, is gradually drawn across the plate, on which, of course, the backs rest. Price from £18 upwards.

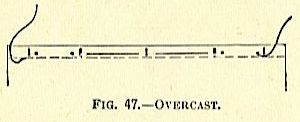

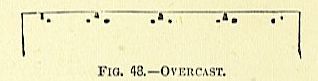

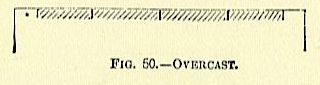

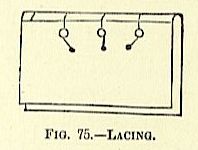

When the first section of a book has a steel engraving pasted to it, or is otherwise composed of separate leaves pasted together, it cannot be sewn all along the middle of the section. It is, therefore, ” overcast,” by making a small hole through it on each side of each kerf (Fig. 47), and passing the needle and thread through up and down, and around the various cords and bands, so that when it is sewn the stitches on the top side lie as in Fig. 47.

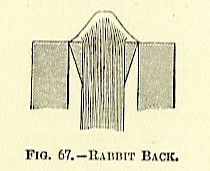

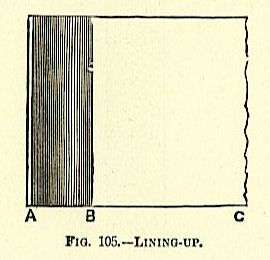

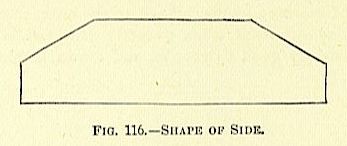

Before the next section is laid down a small piece of thick paste is taken on the end of the forefinger, and the section and stitches are well pasted up to the dotted line (Fig. 47). The next section is then laid on, and this should be well pressed down on to the pasted section with the edge of the folder. In all sewing every few sections should be pressed down with the folder, especially at each side of the cords. When sewing two or more on, the folding-stick is also used to keep the middle of the lower section. When you lay the first section, A, on, and sew from a to 6 (Fig. 40), leave the folding-stick there, projecting from the end. Then section B is sewed on. Now, in order to take the second stitch in section A, from e to f (Fig. 40), all that is necessary is to find the folder, and then the middle of section A is known directly.