ART BOOK BINDING IN AMERICA.

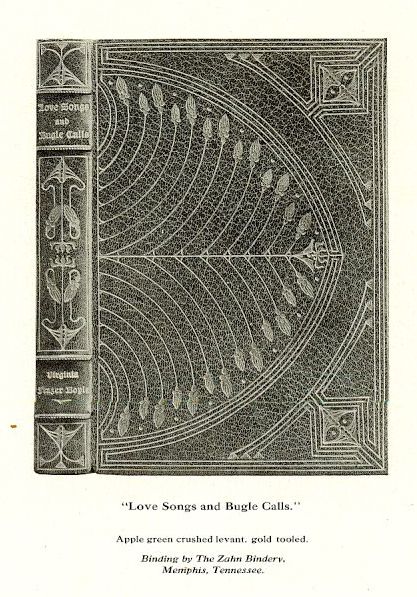

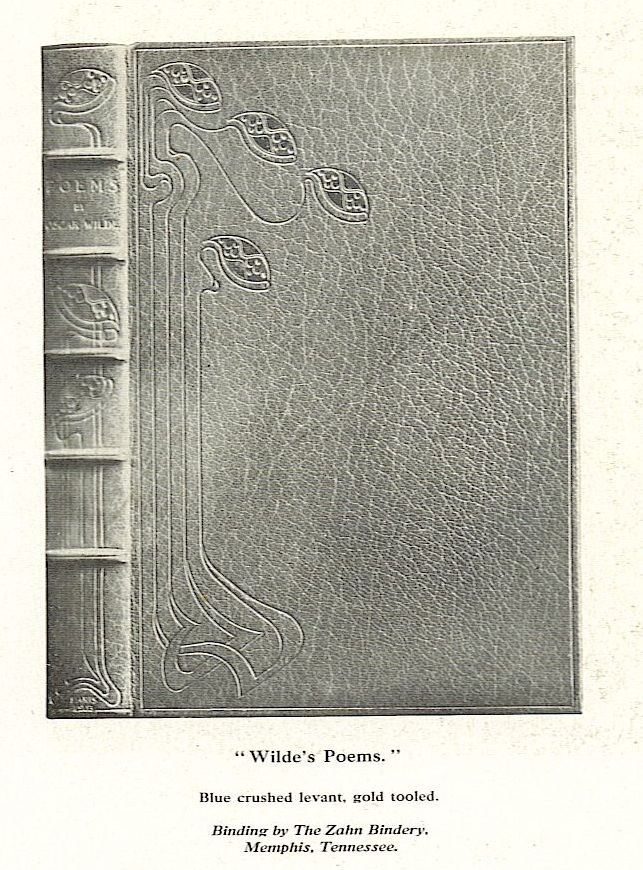

OTTO ZAHN, Memphis, Tennessee

HERE was a time, not very far distant, when anything artistic was entirely disassociated with anything American. The people of this country were too busy with material and industrial development to pay much attention to artistic creations. We had no great historians to rank with Hurne, Macaulay, Grote, Sismondi and Guizot. We had few poets and virtually no novelists. American art was insignificant, and even to this day America can boast no great native composer. But a great many men have in the last quarter of a century made large fortunes in this country ; and with the accumulation of wealth has grown a leisure class. Naturally our millionaires have cultivated a sense of the beautiful, and have become patrons of art. Their homes are palaces, their walls are adorned with the finest paintings in the world, and their libraries would probably rank well with those of the patrons of art and literature in Europe.

There has been a notable development in the art of bookbinding in this country in the last two decades, and people are beginning to realize that there is just as much reason for having handsomely bound books as there is for having beautiful bric-a-brac. The Japanese craftsman who labors patiently and tirelessly over an exquisite piece of cloisonne work which will ornament a mantel piece or a parlor is no more justified than the bookbinder who places in beautiful and enduring form a masterpiece of literature that in its artistic embodiment is not only an ornament but an inspiration and a solace to the book lover.

The last two decades have witnessed a remarkable revolution in the field of book work. Not only has the book itself been improved, both in material and in workmanship, but the artistic idea has been developed correspondingly in all the stages of the book’s production.

Paper, typography, illustration, illumination, and last, but not least, binding, have alike been advanced to a standard of excellence and artistic merit, not attained since the great wave of the Renaissance swept broadcast over the world, carrying inspiration to the artist and artisan of every land.

The tiresome uniformity of the factory product of the seventies and the early eighties with its earmarks of cheapness and general ugliness, has been materially improved upon by the liberal injection of artistic ideas. The handiwork of the individual has come to its honor again—men and women of ideas and imagination have lent their magic influence to the elevation of handicraft. Where two or three decades ago only one or two earnest workers in this country were enthusiastically contending for art in bookbinding, there are now scores of men and women alike successful in the development of this art, in which a few of them have attained a degree of perfection second to none of the great masters of the craft in Europe.

Interest in art and handicraft has been revived by numerous exhibitions, schools, lectures, proper publications and associations of art workers all over the land. The smouldering flames of those aspiring to do things have been fanned into a new flame by a few master-minds who were alike capable of planning and conceiving beautifid books and bindings and skilled in executing them.

The moneyed influences, without which there can be no development of anything, and which formerly confined their investments to buildings, beautiful grounds, stylish gowns, fast horses and perhaps paintings, threw their mighty weight in the balance and for each single book lover who formerly imported his fine bindings from Europe or France, there are now a dozen of them who patronize home industry and thus foster the domestic growth of the art articleic.

I could say much about the art of bookbinding in Europe, but in this article it is desirable to confine myself to its development in this country. As one who was in at the birth of this craft in the United States, I can speak with pardonable pride and an intimate knowledge of the advance made here in the last twenty years. It has not been an easy conflict. Those of us who have been engaged in it have had to create an interest in artistic bookbinding and have had to persuade book lovers that it was not necessary to send abroad to have their precious volumes becomingly bound. We recognize the fact that we have been assisted in realizing our ambitions by the eternal feminine. The astute Frenchman who said “Cherchez la femme” in every important; case, really enunciated a principle as broad as human life. Even in the development of the art articleic in America, there has been the proverbial woman in the case. Indeed, the thorough establishment of the art in this country is due to the tireless efforts of the women. Naturally they love things beautiful, oftentimes at the expense of things useful. American women of means and culture were the first to patronize the art of bookbinding. Their enthusiastic encouragement has enabled the artistic bookbinder to succeed, and their fancy for exquisite books can no more be dismissed as a fad than their penchant for dainty china, or fine paintings, or Pompeian vases. They realize that the pleasure of reading is greatly enhanced by having a book that is well printed on good paper and bound in a form that is agreeable to the eye and pleasant to the touch. Even the best of literature—Shakespeare or Goethe or Moliere himself—suffers from cheap paper, poor type and uncouth binding.

But women have not only served the art articleic by acting as patrons of it, they have embarked practically in its development. They have a natural aptitude for the technical side of the art. They have patience and enthusiasm united with originality and the result has been that the women bookbinders have rendered incalculable service in expanding the art in this country. With their customary quickness they have mastered the details at the same time that they have avoided the temptations to be merely imitators. The mimetic gift is possessed by many of the savage peoples. But it is the creative gift that tells in the great unending struggle for advancement. Women have the mimetic quality which enables them to do with marked success the work that requires an infinite capacity for taking pains; but they have also the imagination that leads them into “green fields and pastures new.” They are not timid and shrinking in any work vitalized by the imagination. They are ready to dare much, and consequently they excel in the originality of their designs, even where they fall short of the best standards. The women bookbinders of America are as a rule women of catholic culture; and they have succeeded. Many of them have made a competency by engaging in the active work of bookbinding while others have derived a competency from teaching. Many indeed have made enough to enable them to study in Europe and perfect themselves in their calling. To the gentler sex we owe much for the encouragement and the development of the art articleic.

France has always led in bookbinding; and American bookbinders have been somewhat handicapped in the race with those who have inherited the traditions and the art impulse of centuries instead of decades. In Europe, on account of the cheap labor, the bookbinders have had an advantage over those of this country. Even the customs duties imposed by this country on foreign importations have not been sufficient to wipe out the difference in the cost created by the difference in the remuneration of foreign and American labor. But in spite of the cheapness of the foreign product, the art of bookbinding has been steadily advancing in America and now it occupies a position from which it cannot be dislodged. This is due no doubt to the high quality of the work done in this country. The bookbinders of America have nothing to ask from those of any other country, and there are enough intelligent wealthy men in this country to know that American work is all right, and to patronize it in preference to the foreign product which may be cheaper without being better.

There is a well known New York club which is engaged in binding works of the best style for its members. In order to have high-class work it imported its finisher from France. Indeed, many of our best craftsmen have come from abroad, and have become citizens of the United States because they realize that this country is the finest field for their endeavor and their skill will prove more remunerative here.

America is now getting time to become an artistic nation. Nowhere in the world are foreign artists more appreciated than in this country. This intense love of art is giving an impulse to the creative artist. Many European craftsmen who come to this country are soon transformed into American citizens. In course of time they will help to leaven the inartistic mass. The art of bookbinding in this country is now on a sound foundation, but it has made only a beginning. The development of the future is apt to exceed all our expectations, and the dominant note is originality, the quality without which no art can ever attain any prominence.

Art and originality indeed go hand in hand in bookbinding. The mere mimetic gift counts for but little, as it requires no more mental quality to imitate others than it does to copy the map of a city.

Having been in close touch with the development of bookbinding in this country from the beginning, I think I can safely say that the promise of the art articleic will be more than realized. Much has been done; but the best is yet to come.