Materials and Stitches

By S. T. Prideaux

I PROPOSE to describe the materials and stitchery used for the old embroidered bindings as well as the designs that decorated them, and show finally what should be the necessary conditions of an application of needlework to the binding of to-day.

The groundwork of the covers was always velvet, satin, or silk. mostly the two first. and of these time has proved velvet to be decidedly the best and most suitable material, and silk the least durable of the three. Nothing is known of the history of velvet, whence it came, or what people made the fortunate discovery of its manufacture. It probably originated, as well as satin, in China; but the earliest places where it was made in Europe are all we know for a certainty, and these were the south of Spain and Lucca. The name “velluto” most decidedly indicates that Italy was the market through which it reached us from the East. It was no doubt fully in use after the middle of the fourteenth century, but is not mentioned in the earliest inventory of church vestments extant that of Exeter Cathedral, 1277, though unmistakably alluded to for the first time in the later one of 1327.

Satin was not known in England either until the fourteenth century. The earlier church inventories have no mention of it, but it is named among the rich bequests made by Bishop Grandison to his cathedral at Exeter in 1340, and the later wardrobe accounts have frequent mention of it.

Chaucer, who died in 1400, mentions it in his ” Man of Lawes Tale”, ” In Surrie whilom dwelt a compagnie Of chapmen rich, and thereto sad and trewe, That wide where senten hir spicerie, Clothes of gold, and satins rich of hewe.’

The Countess of Wilton speaks of Fitchet’s Rhetoric, 1471, as being the earliest embroidered binding extant, and this is to be seen in the library of the British Museum, bound in crimson satin with a coat of arms. Velvet and satin,then, constituted the actual covers of the books. The materials used for their enrichment were floss silks of many colours ; gold and silver threads of various thicknesses, the thinner being called “passing;” and ” purl,” a

material imported from Italy and Germany in the sixteenth century, and henceforth much in vogue. To these may be added spangles, the invention of which has been attributed to the Saracens, and “plate.” This consisted of narrow strips of gold or silver metal beaten thin and stitched on to the work by threads of silk which pass across them, and lizzarding. Spangles are not very often found on book-covers, pearls being much more prevalent in the fifteenth

century, but “plate” was very frequently used, especially as the art gut more debased and striking effects were aimed at without much trouble.

Gold thread was produced by twining long narrow strips of gold or gilt silver round a line of silk or flax, and is probably almost, though not quite, as old a process as that of working up the pure metal itself into a hair-like thread to be either woven into the raw material or embroidered on it. Probably the oldest church vestments were embroidered with this gold wire, though in later times the gold thread mostly took its place. It is possible that the reputation of

Attalus II., King of Pergamus, as an inventor of gold tissues may have arisen from his patronage of thread of gold, for the gold flat plate or wire was certainly in use before his time. It is a fact that in the thirteenth century ladies used to spin the gold thread needed for their own embroidery, for the process which they followed is set forth as one of the items among the other costs for that magnificent frontal wrought 1271 A.D, for the high altar at Westminster Abbey. The bill is to be seen in the Chancellor’s account for the year fifty-six of Henry III. But it was also imported, and the gold threads that still preserve their brilliancy were surely Oriental, and probably came over in the bales of Eastern

merchants. It had various names from the places where it was made, these indicating also its quality. Thus may be seen ” a vestment embroidered with eagles of gold of Cyprus;” and again, “a cope of unwatered camlet laid with strokes of Venis gold,” but in what the difference consisted I do not know, though experts have many theories on the subject.

The first wire drawing machine was invented at Nuremberg in the fourteenth century, but was not introduced in England until 200 years later. “Purl” was a coiled wire cut into lengths threaded on silk and sewn down generally over packthread in the raised portions of the design to give a slight relief. The same word is met with under the form of ” purfling,” and its derivation is from ” pour filer,” to thread on. It was sometimes manufactured with a coloured silk twisted round the metal, though not concealing it, giving a very rich effect. The small corkscrew-like rings made by this coiled wire are very effective, catching the light in a sparkling way, as may be seen in the illustrations. This material is now made in four different varieties, rough and smooth, check and wire check purl. A further kind called bullion is also to be had of gold and silver wire makers. The art was soon discovered of making all these materials an inferior way; in such cases the work has perished, so far as its artistic value is concerned, but in the best days of needlework only the finest of everything was used. In the history of embroidery, accordingly, it is found that much of it has been lost from two contrary causes. What was made of the best material was often melted down for its intrinsic value, and what was decorated with adulterated metal has not stood the test of time. In these days,

when there is no longer anything to fear from the melting-pot, there is no doubt that the metal threads and purl used should be only of the best.

I pass on now to consider the way in which these materials were used, and the kind of stitchery most effective for the purpose of book-covers. The finer kinds of metal thread, called “passing” and ” tambour,” were either worked through the material or sewn on to it with silk of the same colour. Sometimes they were sewn on flat and sometimes raised over thread or even cord if the relief was to be high, but silk embroidery was never thus raised. They were mostly used double, the lines being laid down side by side and only the ends passed through from the back. Occasionally, too, they were sewn down with a bright red silk that added lustre. This kind of work, in which the gold thread is stitched on the surface by threads coming from the back of the material, is called “couching,” or ” laid ” work, and the ancient modes of couching were very numerous, zigzags, wave patterns, and all kinds of diapers being produced by the position and arrangement of the stitches that control the gold thread. This use of very fine passing is not often found on book-covers, but there is one in the MSS. Department of the British Museum which, though much worn, is an interesting specimen of this class of work. It is a Latin psalter of the commencement of the fourteenth century, which belonged subsequently to Anne, daughter of Sir Simon de Felbrigge, a nun in the convent of Brusyard, in Suffolk, to which she bequeathed it, and where the figures were probably wrought. Only the panels now remain. Let into the sides and patched with leather, these represent on the upper side an Annunciation, and on the lower a Crucifixion. The figures are of the finest workmanship, and stand out on a ground wrought with a gold thread caught down in a wave-like pattern. Different sizes of twist gold were employed for scroll work or for outlining leaves and flowers, or bordering the raised parts of the design in which purl was used.

The kinds of stitches used in the gold and silk embroideries are comprised in classical and mediaeval authors under six heads, four of which are to be met with on book-covers. First of all is that termed Opus Phrygium, or Orphreys, as it was called in the Middle Ages, which includes all passing and metal thread work above described. It was so named in the beginning because the Phrygians had attained to the utmost perfection in the art when conquered by

the Romans, who imagined them to have invented it, being unaware of the success of the Chinese in tissue ornament likewise. The Romans imported and domesticated the art, and afterward applied the name to all work in gold.

Opus Pulvmarium, or cushion work, includes all stitches regulated by the thread of the material, such as mosaic, cross and tent stitches, as well as chain stitches.all, in fact, except the flat ones. It is considered to have been so alled because the stitches, being firmly set, were found most suitable to shrines and cushions. Under the name of Berlin work it has become wholly debased, but what its effect can be may be seen in a little volume of Psalms in the British Museum, covered in canvas worked all over in tent stitch.

Opus Plumarium, or feather work, embraces all flat stitches.of which the distinguishing mark is that they pass and overlap each other.such as those known as ” satin,” ” stem,” ” twist,” and ” long and short” stitches. This class has more of inspiration in it than any other, as the design may grow with the freedom of stitches that are not counted but wrought at the will of the worker. The origin of the word is obscure. Pliny ; mentions the Plumarii as craftsmen in the art of acu pingere, or painting with the needle, and it is probable from the feather patterns found in Egyptian art that first feathers themselves and later the imitation of them were used in the adornment of textile fabrics. Feather application was therefore most likely the first motive of the word, which was aftewards extended to the stitches which conveyed a similar effect.

All these three classes are to be found exemplified either alone or in combination upon book-covers. I give the remaining three for the sake of completeness. They are : Opus Consutum, cut or applique work, and of this there is one example on a binding in the British Museum.the only one I have so far come across. It is here reproduced on account of its quaintness and as being a unique specimen. The Opus Araucum or Filatorium, net or lace work, and the Opus Pectineum, tapestry or combed work, are naturally not represented on book-covers.

It is almost certain that the application of embroidery to binding was essentially an English art, and nearly all the examples in our national collections are of home workmanship. The Bibliotheque Nationale has two on view in the rinted Books Department, and two in that of the MSS. Department, which are of native work; there may be more, but according to the rules of the library it is impossible to make any researches from the point of view of a particular art,

as one must know the title of the book before one can get access to it. Both those in the first department are folios.one bound for Louis XIV. in blue satin has his arms wrought in gold, silver, and silk, and those of France, and Navarre in the corners; the other, bound for Louis XV. in crimson velvet with gold embroidery, has a water-colour portrait of the king on the front side, and the arms of France on the other.

Les Gestes de Blanche de Castille,” Queen of France, in the MSS. Department, dedicated to Louise de Savoie, one of the many French ladies who had a famous and well-bound library, is covered in black silk, the stitchery representing a hunting scene as well as the presentation of the book to Louise. The most interesting one of the four is a small collection of prayers of the end of the fifteenth century. Inside the boards are portraits.probably of the possessors, the book itself being covered in an embroidery in very fine cross-stitch representing the Crucifixion with the Virgin, St. John, and the angels.

In France, however, embroidery was more frequently used as a mere envelope for a book of devotion, richly tooled when the owner was in mourning, and desirous that nothing gay should disturb the sombre note of her apparel. Such a one Monsieur Gruel lately discovered sewn on a binding still fresh in appearance, and dating from the seventeenth century.

Some of the old books treating of the art of needlework are very valuable ; of others, indeed, only the titles are known. It is rather a curious fact that the English specimens are all after Elizabeth’s reign, when embroidery had ceased to be a necessary part of education. Their disappearance may perhaps be accounted for by their having been cut to pieces, and used by women to work over or transfer to samplers. Mr. Donee, in his illustrations to Shakspere, has a list of some of these books. There is one which, from the dress of a lady and gentleman in one of the patterns, appears to have been originally published in the reign of James I. It appears that the work went through twelve editions, and yet a copy is now scarcely to be met with, it is entitled “The needle’s excellency, a new booke, wherein are divers admirable workes. wrought with the needle. Newly invented, and cut in copper, for the pleasure and profit of the industrious. Printed tor James Boler, 1648.”

Beneath this title is a neat engraving of three ladies in a flower garden, under the names of “Wisdom”, ” Industrie”, and ” Follie.” Prefixed to the patterns are sundry poems in commendation of the needle, describing the characters of ladies who have been eminent for their skill in needlework, among whom are Queen Elizabeth and the Countess of Pembroke.

If the art of embroidery in its application to binding is ever to come into fashion again, some lessons may be learned from its similar employment in past times. And at the, outset it may be said that it is only applicable within certain limits. Books chosen for decoration by needlework should be such as are not meant to be stood np in a bookcase, but rather intended to lie on a, table or be kept in a case. It follows, one would think, that the work should appear only on the upper side of the book, unless it is of so flat a nature as not to interfere with its recumbent position. It is true that nearly all the old embroidered covers were worked on both sides, but most of them are much more worn on the under side, the appearance of the whole being thus greatly marred by the discrepancy between the freshness of the two sides. If the design is not in relief at all, being worked in silk and without metal thread or purl, it can appear satisfactorily on both sides. Another condition is that the material should be velvet rather than silk or satin, as being much, more durable, not only in its texture, but also in the colours in which it is generally made. A great many of the, old embroidered books that have survived are worked on silk or satin of very delicate colours, and with silks equally delicate in hue, giving artistically the most charming results. But the conditions of modern life, with its smoky towns and constant struggle with dirt, render such materials quite unsuitable to these times, while a, good rich-coloured velvet has an immense, amount of wear in it, and is more dirt-resisting than many a delicate-coloured calf or morocco.

Velvet, then, being the most suitable covering, a further limitation is brought about in the materials with which it should be worked, there is no doubt that gold and silver passing of the best kind, in conjunction with purl, looks best on velvet, and that silks are more suited to the ground with which they naturally correspond. On velvet only is it worth while expending the time and trouble of an embroidered design. There is a book in the British Museum bound in purple velvet, and worked with silver purl and passing which is an example of the style of work I think most adapted for revival, and which is reproduced here chiefly on account of its suitability.

There is another to he seen in one of the show-cases of the museum entitled ” Orationes Dominicae Explicatio,” bound for Queen Elizabeth in 1583, which in material, colour, and design is the most perfect example of this style of work. It was pictured in THE WOMAN’S WORLD for November, 1888, and I strongly recommend It as the ideal to be aimed at. Bound in dark green velvet, the sides are completely filled by a well-balanced design of comparative simplicity, worked with coachings of gold twist, the roses and leaves being treated with purl on a slightly raised foundation. A final condition of the success of this work, but the most important of all, is that the design should be simple and appropriate.

I may roughly class the embroidered bindings that are within reach as materials for study under four heads.Those with heraldic arms blazoned on velvet; those with scroll work in couchings of twist and metal threads mixed with purl, having either velvet or satin as groundwork ; those wrought with silks on silk or satin; and those covered entirely with fine tapestry stitch in silk on a linen or canvas ground, no part of which appears. In comparing these different classes one is impressed by the fact that the simplest in design are both the most effective and the most pleasing. Here and there may be seen one that is both complicated and successful, but not often.certainly so rarely that in reviving the art complication of design would be avoided rather than the reverse. The two first classes are the most attractive and suitable for models; there is always a distinction about coats of arms, and set on a line coloured velvet with a simple, border of gold twist they are both simple and effective.

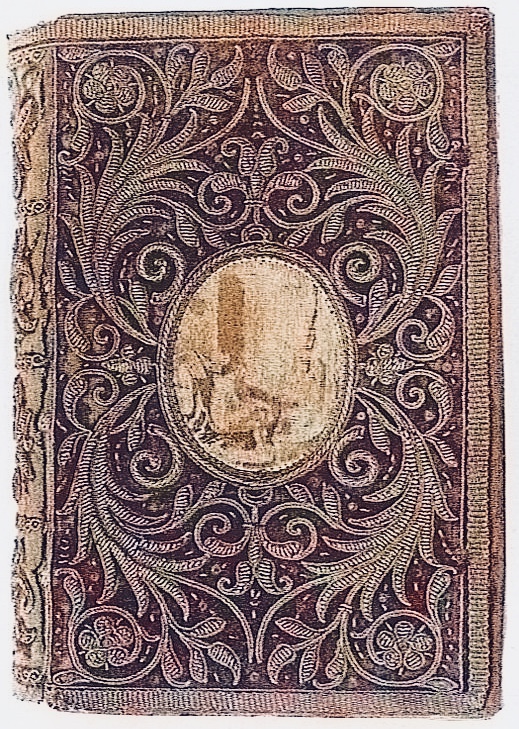

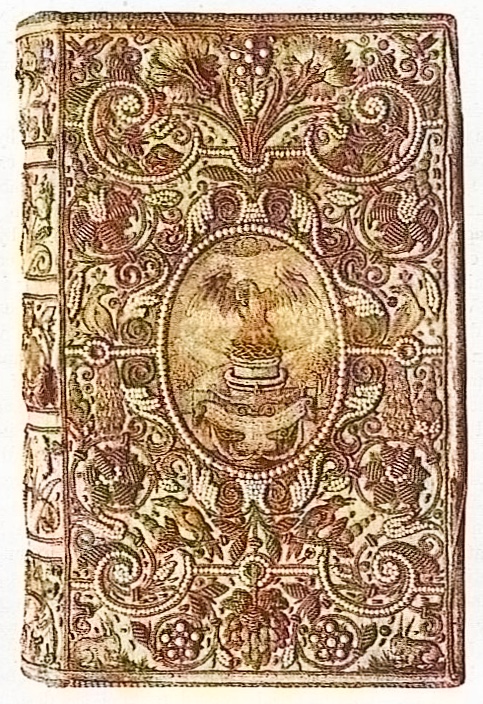

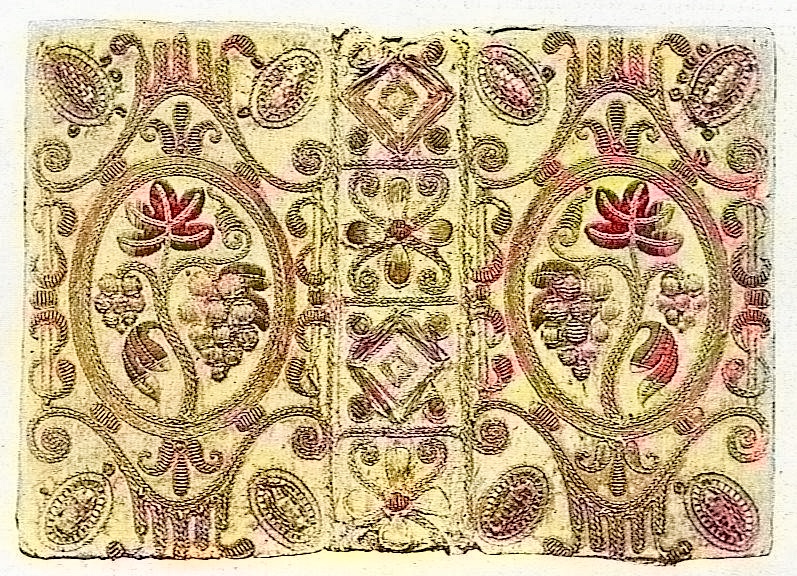

The three first illustrations given are from the South Kensington “Museum. The first is that of a white satin cover, richly embroidered hi seed pearls and coloured silks which have not lost their brilliancy, the whole being in a remarkable state of preservation. The second shows a blue velvet cover worked with silver purl, the back of which is also given as having an extremely original design. The third gives a design in gold purl on a maroon coloured velvet. The last is from the British Museum, a white satin cover with a graceful design of grapes and vine leaves, set in a Renaissance frame of silver twist and thread. In the beginning of this century a French binder called Lesne wrote an elaborate poem in favour of his craft, which, like similar poems with a purpose, is not of any great merit as literature. But it contains some good things, and, among others, two lines which should become the motto of every craftsman:

” Un art n’est qu’un metier dans une main vulgaire; Un metier est un art quand on le sait bien faire,”