It is intended that the foregoing shall show the progress which is being made towards a higher average wage, and without doubt, the next few years will see still more advancement. But until the unskilled labor in the bindery, which is as a rule young men and girls, becomes trained, and during which time it is assumed they live at home, the real minimum wage must be kept below $9.00 per week.

Employers have awakened to the fact that by protecting their employees’ health, and paying them the maximum wage for the class of work performed, they are gaining the best results. In some states, particularly in New York, cuspidors are provided and regularly cleansed, thus removing to a certain extent, the spread of tuberculosis which it has been known was prevalent in binding plants. In one instance at least, female employees are being provided with gowns and caps to protect their clothes and hair from the dust which floats around especially in the sheet department. Machinery is being better protected against accident and more attention is given to avoiding the operation of machines by unskilled labor where danger exists.

The old dingy factories in the cities, and even in the suburban sections, are passing, and the new cement-steel buildings, made as nearly fireproof as possible and with ample lighting facilities, are taking their places. It is known that the wearing of glasses, which was forced upon employees in these old style buildings, is gradually diminishing- -another evidence of progress.

Never was there so much evidence of co-operation on the part of employer and employee; never so great progress in safeguarding the employees’ health and interests; in a word, never has there been such development in the betterment of the plants, as a whole, throughout the country. This in turn has influenced business and today the plant that is paying particular attention to these details is reaping the benefit, and will be found to be the plant which is steadily forging ahead.

A marked change has taken place in the methods of securing and handling work. Not so many months ago, a binder worked from hand to mouth. There were the busy seasons and the quiet seasons; the good was taken with the bad. This has changed materially in the past year. Publishers formerly worked on the old “rule of thumb” methods. Little attention was given to the actual specifications under which their books were produced. So long as a book had an attractive type page, was printed on pleasing paper, bound with some semblance of attractiveness, held together long enough to satisfy the customer, and yielded a profit to the publishers, it was satisfactory. All this has changed. Today the publisher, that is, the wide-awake publisher, is following much the same plan as the up-to-date binder in standardizing, in demanding certain grades of material, and insisting that his books be bound along lines which have been found to be productive of the best results.

The American Library Association has done wonderful work in this line, and its committee on binding, with Mr. A. L. Bailey of Wilmington, Del., as chairman, is to be particularly commended. It has influenced several of the publishers to adopt specifications which investigations and severe tests have determined to be the best, and it has been productive of excellent results. These specifications will be mentioned later.

Much has been done to bring to a basis of uniformity, the various books put out all over the country with regard to size, make-up and general specifications for the different characters of work represented. Much attention has been given in the heavier bindings to the government specifications for buckrams, as well as for other cloths and leathers. The foremost publishing houses of today are reducing their publication list to standard units, or series, and instead of a conglomerate mass of perhaps 2,000 titles, all of varying sizes, they are now grouped into series as fast as they are republished, thus making for uniformity of records, reduction in cost of manufacture, and elimination of errors between printer, binder and publisher.

The majority of publishers formerly took no interest in the processes of binding, but simply asked for bids on so many pages, in such a cloth, and so much stamping. The lowest bidder secured the contract. No attention was given to impositions, grain of papers, and when a shortage occurred between the printer and binder, it was an occasion for general contention. It is gratifying to state that today the conditions have changed. The publishers of consequence are now employing men in their manufacturing departments familiar with the actual productive processes, and are standardizing not only their titles, but each individual process of a series.

All binders are familiar with the difficulty encountered in increasing a binding price when the sheets sent them by the printer are not imposed for machine folding, or if imposed for machine folding have incorrect guide edges, omitted point holes or slit points. It was the publisher’s contention that the binder should have notified the printer, and the printer’s contention that the publisher should have notified him, or vice versa. Today, in many instances, the binder is requested, at the time of submitting a quotation, to specify the required imposition, or if he is keenly alive to his position as a binder, he states in submitting his estimate the imposition desired. Printers, as a rule, cannot understand why a binder does not have in his plant machines which will fold every conceivable kind of an imposition, from the time of Caxton down. By stating definitely the imposition which is required, the binder protects himself and incidentally protects the publisher and eliminates the printer from assuming responsibility. In this way shortages are oftentimes prevented. Publishers today are allowing definite percentages for spoilage in the pressroom and bindery; printers, as a rule, are giving more attention to the delivery of full count quantities to the binder, and the binders, are paying strict attention to the delivery of the full count of good signatures from folding machines, and the make-up of full editions of gathered books in every instance. This results in an element of satisfaction which formerly was often lacking. On reviewing the situation, we find that the publishers are paying strict attention to the details of binding their books. The binder who formerly made out his order to bind “the same as before” with the addition of the number of copies, the order number, and the publisher, is in the background. The up-to-date binder has an established order system, which gives him the complete specifications for every job he handles, and with the aid of the publisher who is standardizing his titles and assembling them in groups, this is simplified.

For many years, the binder has constantly complained that the publisher and printer paid little or no attention to the grain of papers. It seemed almost as though they were not familiar with the fact that it was advisable, and in coated papers imperative, that the grain of the paper run parallel with the backbone of the book. Papers can be obtained with the proper grain, and if publishers in the future will pay more attention to this detail, and binders insist that they pay attention to it, the possibility of producing good books will be increased. i

The matter of shortages between the printer and binder has always been viewed by the publisher as a necessary evil. It is interesting to note that considerable progress has been made in the past few months toward a more hearty co-operation on this point. Printers should view the honest binder not with suspicion, and the idea that he is desirous of spoiling as many sheets as possible, but with a more open-minded view that the more copies he produces the more he gets, and he, even more than the printer, is disgusted with a shortage. It can almost be said that co-operation is replacing unfair competition, although competition in the various lines continues keen. There are still instances where unprincipled binders are governing their quotations by the condition of their plant, but as these binders get into modern ways, they are gradually understanding that a uniform basis of figuring shows up better on the balance than a fluctuating schedule dependent upon whether their plant is running to its fullest capacity or not.

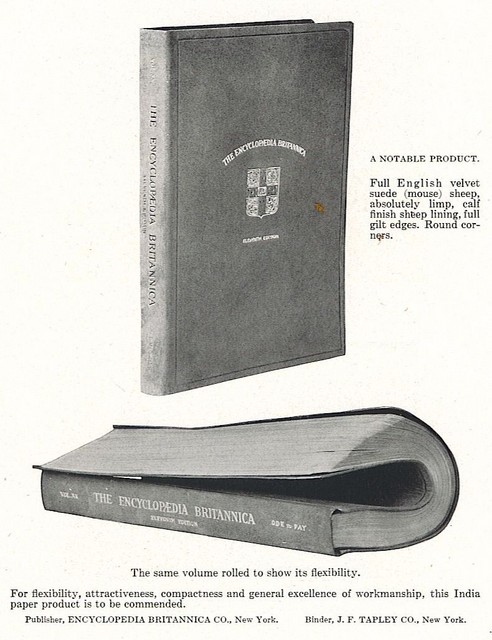

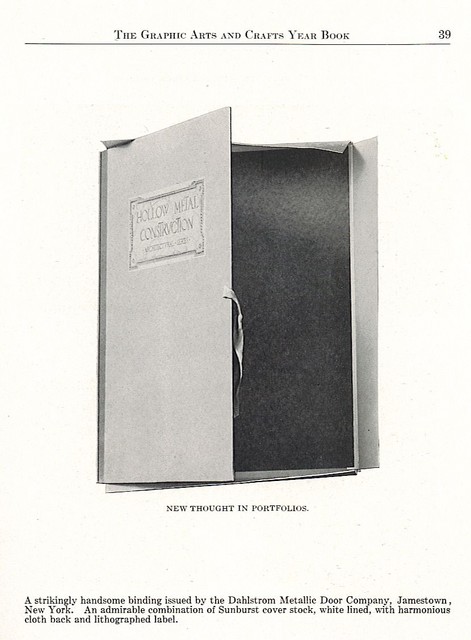

Among the larger houses more attention is given to the credit standing of their customers. In many houses the credit man has become an important factor, and where many chances were taken heretofore, bad accounts are now being reduced by the assistance of the trade mercantile agencies, and the information secured by the active salesmen, who have now become an important element in the business. It is hoped that the binders will be even more particular in the coming year, refusing credit to those of unstable standing financially, insisting particularly upon uniform terms of payment, and a uniform basis upon which business is handled. A particularly fine attempt along this line has been made by the J. F. Tapley Company of New York, who send out a letter with each estimate, known as their “terms and condition letter/’ In this they state in part that they reserve the right to fold, plate and gather all unordered sheets sent to them, and the customer is to reimburse them at the expiration of one year for such labor and material as they have used on the same. They also state that all completed work is to be charged when finished, and shall be taken off their hands within a period not exceeding six months, except under special agreement. An important feature is their statement that all sheets, plates arid other material entering into the make-up of a book, shall be delivered f. o. b. their bindery, and in turn they will deliver the completed product, unless otherwise stated, in bulk within a certain radius from their plant. They care for another item which has hitherto been one of discussion, that of furnishing dies for the stamping of covers. They distinctly state that these are to be furnished by the customer. In addition to this is a statement concerning agreements being contingent upon strikes, fires, accidents, etc., and that they assume no insurance on their customers’ goods beyond the value of their labor and material until charged. They state particularly that the terms are to be net cash on the 10th of the month for all goods delivered during the previous month; that quotations are made contingent upon credit being satisfactory, and that the giving of credit and acceptance of notes does not affect their lien, which shall attach to all completed and uncompleted work, should that which has been delivered or held in stock not be paid for. A universal custom among binders of submitting such a statement with their quotations, would be conducive to more prescribed lines in the handling of customers’ accounts, and to a general condition of satisfaction and understanding which has not hitherto existed.

The folding and gathering of entire editions, which originated with this company, has met with universal approval and is now being adopted throughout the country in the most progressive plants. It is the logical solution of the storage and quick handling problems.

The sales departments in many binderies have been brought to a high standard of efficiency. In many cases it was formerly the custom to make a quotation and then forget it. If the order came in it was accepted; if not heard from, it probably did not come up again until the next year. Today, the plant keenly alive to the situation has its sales manager, its salesmen and its sales organization, which provides for a complete cataloging of publishers, printers and individuals who publish, or are liable to publish books. A constant circularization is made, likewise an attempt to make as many calls by the regular salesmen as are deemed necessary for the amount of business handled. i

The organization of the bindery in conjunction with the handling of the details incident to binding with the publishers, has undergone radical changes in the past few months. The binder is striving to please the publisher in ways never before thought of. In many instances, the binder is the publisher’s manufacturing assistant, in the sense that he enables him to standardize, and by units assemble his productions into a uniform series. The thoroughly-organized plant is now able to live up to its promises, and repudiate that old farce known as a “binder’s promise/’

It can safely be said that should the binders who have not already realized the advantages of reorganizing, fall in line with this advance movement, which is truly progressive, the contentions between the binder, printer and publisher would be materially lessened, thereby making the work of each, and particularly the binder, much less a mass of detail and more particularly a work of pleasure.

The binder aiming to keep abreast of the times in machinery, equipment and organization, has found his time well taken up, if during the past year, he has attempted to familiarize himself with all of the new processes and new machines which have been introduced. Many machines which have been undergoing the period of experimentation and perfection, have developed into units to be considered. There have been several machines placed upon the market for which unusual savings in cost of operation and output has been claimed, but until those machines have demonstrated over a period of time, that they can fulfill all of the claims made for them, they cannot be considered items of interest to the practical binder. j

Looking for a moment at the subject of folding machines, we find that several new developments have made been. With the introduction of the larger-sized reference books printed on India paper, it became necessary to evolve a machine, the delicate mechanism of which would be capable of handling the India paper sheets in large sizes with a minimum of spoilage, and with an accuracy of register which would be acceptable. This machine had also to make the fourth fold, thereby delivering a single 32 and in such a manner that the air, which was pocketed in the folds, would be expelled and the signature be delivered flat without bulkiness. Taking the regular 32-page jobber machine as a basis, Chambers Brothers Company of Philadelphia, have produced a machine which to the author’s intimate knowledge accomplishes the desired results.

In quadruple machines many new developments have appeared, chief among which has been the arrangement of perforators for the signatures, thus enabling a binder to fold much heavier sheets on the quad than was formerly possible. With the adaption of the machines to deliver either four 16’s separately, two inserted 32’s, or an inserted 32 and two 16’s separately, quadruple machine-folding is rapidly coming into its own and binders are realizing more than ever before that wherever the stock will permit, it is more economical to use the quadruple imposition, particularly where the slit points are available, giving an opportunity to overcome varying guide edges without resorting to hand folding.

Double-16 machines of the drop roll type have been improved to the extent of handling sheets to deliver in two 16’s, an inserted 32, and can even be equipped with an attachment in the Dexter type, for turning out two sections of 32 pages, provided the paper is riot too heavy.

The Chambers’ type has been improved to what is known as a quadruple 16 on the drop roll basis with an inserting feature. This machine is an adaption of the quadruple principle combined with the drop-roll unit idea. It will deliver four separate 16’s, can be adjusted to insert and deliver two 32-page sections, inserting before the third folds are made, or can be adjusted so that one-half of it inserts, delivering one 32, with the other half operating for the delivery of two separate 16’s. This has been found to be a valuable feature for getting out a single 16 on some books where it is desired to run the front matter and the index matter last, and thus enables the arranging of a 16 for the front of the book with a 16 for the back.

Another unique feature is the running of two or more upon a sheet, folding as a regular 16 or 32, and after gathering and sewing, cut into units. In pamphlet binding sheet can be handled to final trimming before cutting apart.

In the magazine line, the quadruple folder now takes a flat sheet, cuts it into four sections, calipers, registers, and folds one long fold through the four sheets, and after folding cuts the sheets apart again, the sections being delivered independently into separate boxes. This particular machine is known as the Dexter Open-Edge Magazine Folder, and by its operations eliminates trimming and waste paper.

The Dexter double-deck folder for periodical work, made in either two 16’s or a 32-page folder, built in one frame one above the other, both automatically fed, has been brought to a high standard of efficiency. One of these machines when coupled with an insetting, cutting and stitching machine, gives a combination for periodical work that it is hard to surpass. i

There have been many new jobbing machines designed for the small book or pamphlet work, and prominent among these are the latest types produced by Cleveland, Hall and Anderson. These have been given considerable attention during the past year, and it can be said, they are now at their best.

Passing through the bindery in retrospect, we find an imported pasting machine which has been found useful in some lines of insert work, but for general book work has not been found economical. Little or no change has been made in the gathering machines, sewing machines and smashers in the past year.

In trimming machines we find a new idea known as the Rowe Continuous Book Trimmer put out by T. W. & C. B. Sheridan Company. Working on a horizontal continuous feed principle with rotating knives, an enormous capacity is obtained.

In stamping presses new ideas have appeared, principal among them being the increase in the strength of the arms, particularly on the combination embossing and inking presses, and in a new press being put out by Sheridan, the travelling bed principle is predominant. This also has a triple toggle construction for which is claimed an absolute uniformity of pressure.

A machine which will interest; the large binder handling considerable foil, leaf or gold stamping, is the Drexler Cover-Cleaning Machine. This, operating with a brush on a sweep arm, removes surplus leaf from the covers and deposits the refuse in a container. When working with genuine gold leaf it has a saving device of merit. i

The use of large quantities of genuine gold leaf year after year in bookbinding, resulted in investigations for the use of roll gold on covers. Working in conjunction with the Tapley Company of New York, the American Roll Gold Company of Providence, R. I., has evolved gold-laying machines which actually roll the gold in varying widths suited to the requirements of the lettering, with a minimum of waste, and with a reduction in labor of about 40%. Exhibits of the work of the gold-laying machine will be found throughout this article. j

While it could hardly be said that the removable binder’s press originated during the past year, its adoption has become more uniform and the binder with from fifty to one hundred standing presses is hard to find. The majority have sold out their standing presses with the exception of half a dozen, and are using the knock-down removable press, which requires little or no space when not in use, is as rigid as the standing press after the books have been built in, and has the added transporting feature.

With the most modern ideas in machinery has come the problem of disposing of equipment which is used only part of the time, but which is absolutely essential when needed. The unit idea as applied to machines has solved this problem. In many plants floor space is limited. A machine may be needed for three months of the year, or for perhaps two weeks of a month.

Mr. A. C. Wessmann, President of the J. F. Tapley Company of New York, has developed an idea which will interest all binders. Every machine which can be so handled is mounted on a platform made as small as will accommodate the machine and its equipment. The illustration (page 16) of a Smythe book-sewing machine, with feed table, cutting table and individual motor attached, will serve as an example of this principle. The machine can be rolled on to the elevator and stored away in the storage floor until needed. If space is limited, the machine can be set anywhere and connected with the lighting circuit, as an individual motor operates on a voltage which coincides with the lighting circuit.

The Tapley Company has applied this principle not only to sewing machines, but to punching machines, small folders, stitchers, round cornering machines, cover benders, and it has been found that by removing from the factory floor every machine that is not in operation, or that is not required for work for several days, considerable saving in time can be made in the handling of the products passing through the manufacturing floor at that time.1

It is interesting to know that the old-time binderies with their lines of shafting and belts, are now a thing of the past. The up-to-date plant has every machine equipped with its individual motor; a diffused lighting system installed for work on tables and floor, with direct lighting for machines and at other points where the light is required at a particular operation. i

With the standardizing of materials, tools and equipment, and the building up of one continuous unit idea in the bindery, has come the possibility of scientific planning of work. One of the results of scientific management as applied to the bindery, has been the routing of work. In other words, every order passing through the bindery is scheduled before the order leaves the office to be handled by certain employees, on certain machines, at certain times, and to be delivered upon certain dates. The contention often arises that this is impossible, that delays will occur. With a well-organized planning department, and with routing foremen familiar with equipment and methods, little or no delay or mix-up occurs, and far less chance of error is possible,,

With scientific management has come scientific planning of the plant from one end to the other. One can start at one end of the plant today and walking almost in a straight line from floor to floor, can follow the progress of a book from the unpacking of the sheets to the packing of the completed books for shipment. The old truth, that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, is again proven. From cutting machine to folder, from folder to pasting table, from pasting table to gathering machine, from gathering machine “to collator, on to the sewing machine, smasher, and then to the trimming, each group is in a straight line and arranged conveniently to each other.