The Barons

The Twenty-five Barons Appointed to Enforce the Magna Carta

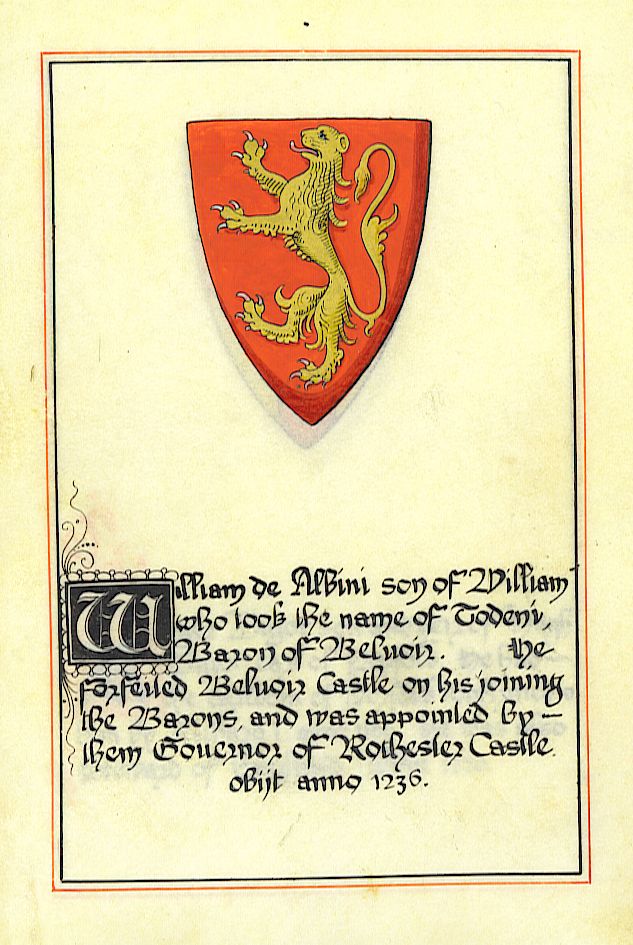

William d’Aubigny, Lord of Belvoir Castle.

William d’Aubigny or D’Aubeney, Lord of Belvoir (died 1 May 1236) was a prominent member of the baronial rebellions against King John of England. William was the son of William d’Aubigny (Brito). William’s ancestor Robert d’Albini de Todeni came to England in 1066 with William the Conqueror After the Battle of Hastings, Robert was given many properties, possibly as many as eighty, among them was one in Leicestershire, where he built Belvoir Castle. This was his family’s home for many generations. William stayed neutral at the beginning of the troubles of King John’s reign, only joining the rebels after the early success in taking London in 1215. He was one of the twenty-five sureties or guarantors of the Magna Carta. In the war that followed the signing of the charter, he held Rochester Castle for the barons, and was imprisoned (and nearly hanged) after John captured it. He became a loyalist on the accession of Henry III, and was a commander at the Second Battle of Lincoln in 1217. He died on 1 May 1236, at Offington, Leicestershire, and was buried at Newstead Abbey and “his heart under the wall, opposite the alter at Belvoir Castle”. He was succeeded by his son, another William d’Aubigny, who died in 1247 and left only daughters. One of them was Isabel, a co-heiress, who married Robert de Ros, 1st Baron de Ros (c. 1212-1301), thus adding the Aubigny co-guarantor of the Magna Carta to the pedigree of George Washington, 1st president of the USA.

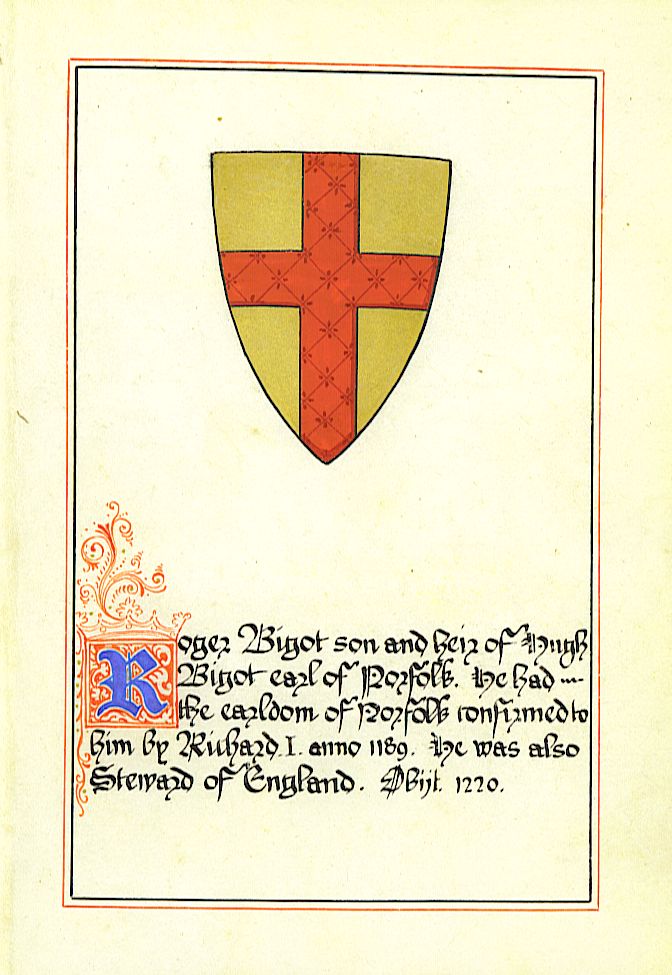

Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Roger Bigot (died 1107) was a Norman knight who came to England in the Norman Conquest. He held great power in East Anglia, and five of his descendants were Earl of Norfolk. He was also known as Roger Bigod, but as a witness to the Charter of Liberties of Henry I of England he appears as Roger Bigot.

Roger came from a fairly obscure family of poor knights in Normandy. Robert le Bigot, certainly a relation of Roger’s, possibly his father, acquired an important position in the household of William, Duke of Normandy (later William I of England), due, the story goes, to his disclosure to the duke of a plot by the duke’s cousin William Werlenc. Both Roger and Robert may have fought at the Battle of Hastings, and afterwards they were rewarded with a substantial estate in East Anglia. The Domesday Book lists Roger as holding six lordships in Essex, 117 in Suffolk and 187 in Norfolk. Bigot’s base was in Thetford, Norfolk where he founded a priory later donated to the great monastery at Cluny. In 1101 he further consolidated his power when Henry I granted him licence to build a castle at Framlingham, which became the family seat of power until their downfall in 1307. Another of his castles was Bungay Castle, also in Suffolk. Both these were improved by successive generations. In 1069 he, along with Robert Malet and Ralph de Gael (the then Earl of Norfolk), defeated Sweyn Estrithson (Sweyn II) of Denmark near Ipswich. After Ralph de Gael’s fall in 1074, Roger was appointed Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, and acquired many of the dispossessed earl’s estates. For this reason he is sometimes counted as Earl of Norfolk, but he probably was never actually created earl. He acquired further estates through his influence in local law courts. In the Rebellion of 1088 he joined other Anglo-Norman barons against William II, who, it was hoped, was to be deposed in favour of Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy. He seems to have lost his lands after the rebellion had failed, but got them back again. In 1100, Robert Bigot was one of the King’s witnesses recorded on the Charter of Liberties, an important precursor to the Magna Carta of 1215. In 1101 there was another attempt to bring in Robert of Normandy by unseating Henry I, but this time Roger Bigot stayed loyal to Henry. He died on 9 September 1107 and is buried in Norwich. Upon his death there was a dispute between the Bishop of Norwich, Herbet Losinga, and the monks at Thetford Priory, founded by Bigot. The monks claimed that Roger’s body, along with those of his family and successors, was due to them as part of the foundation charter of the priory (as was common practice at the time). The issue was apparently resolved when the Bishop of Norwich stole the body in the middle of the night and dragged it back to Norwich. For some time he was thought to have two wives, Adelaide/Adeliza and Alice de Tosny. It is now believed these were the same woman, Adeliza(Alice) de Tosny(Toeni,Toeny). She was the sister and coheiress of William de Tosny, Lord of Belvoir. He was succeeded by his eldest son, William Bigot, and, after he drowned in the sinking of the White Ship, by his second son, Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, who later became Earl of Norfolk. He also had 3 daughters: Gunnor, who married Robert, Lord of Rayleigh; Cecily, who married William d’Aubigny “Brito”; and Maud, who married William d’Aubigny “Pincerna”, and was mother to William d’Aubigny, 1st Earl of Arundel.

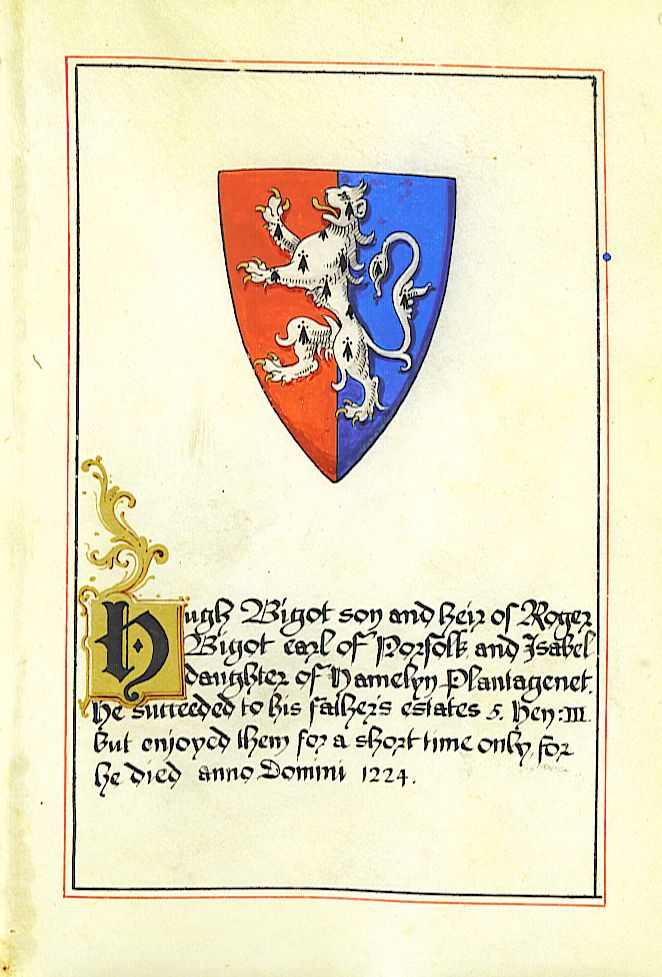

Hugh Bigod, Heir to the Earldoms of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk (1095 – 1177) was born in Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire, England. He was the second son of Roger Bigod (also known as Roger Bigot) (d. 1107), Sheriff of Norfolk, who founded the Bigod name in England. Hugh Bigod became a controversial figure in history, known for his frequent switching of loyalties and hasty reactions towards measures of authority.

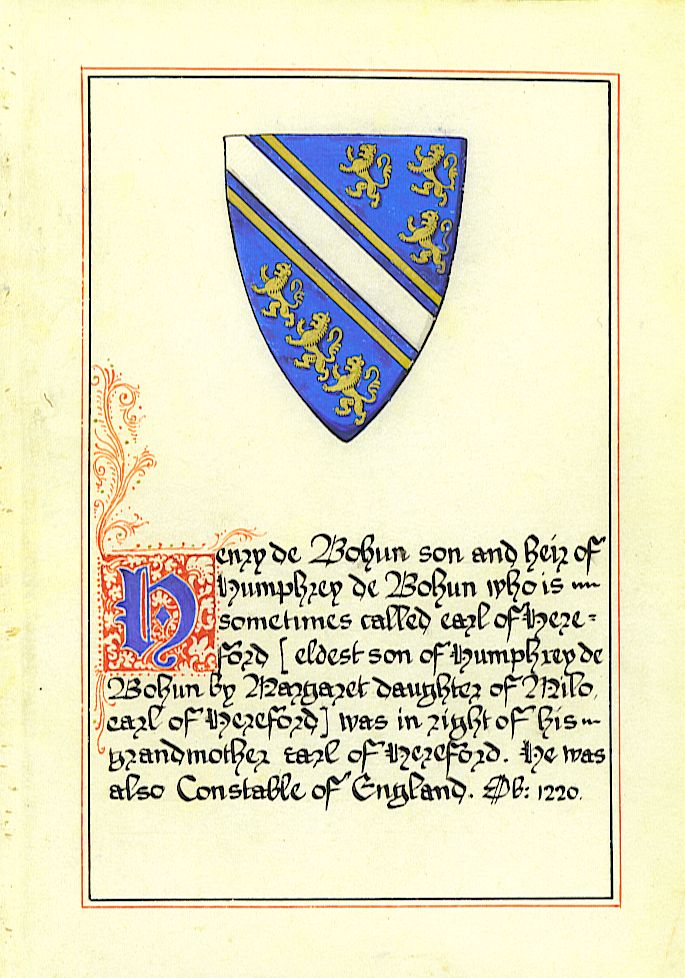

Henry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford.

Henry de Bohun, 1st Earl of Hereford (1176 -1220) was an English Norman nobleman. He was Earl of Hereford and Hereditary Constable of England from 1199 to 1220.

He was the son of Humphrey de Bohun and Princess Margaret, daughter of Henry of Scotland, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, a son of David I of Scotland. His paternal grandmother was Margaret, daughter of Miles de Gloucester, 1st Earl of Hereford and Constable of England. Bohun’s half-sister was Constance, Duchess of Brittany.

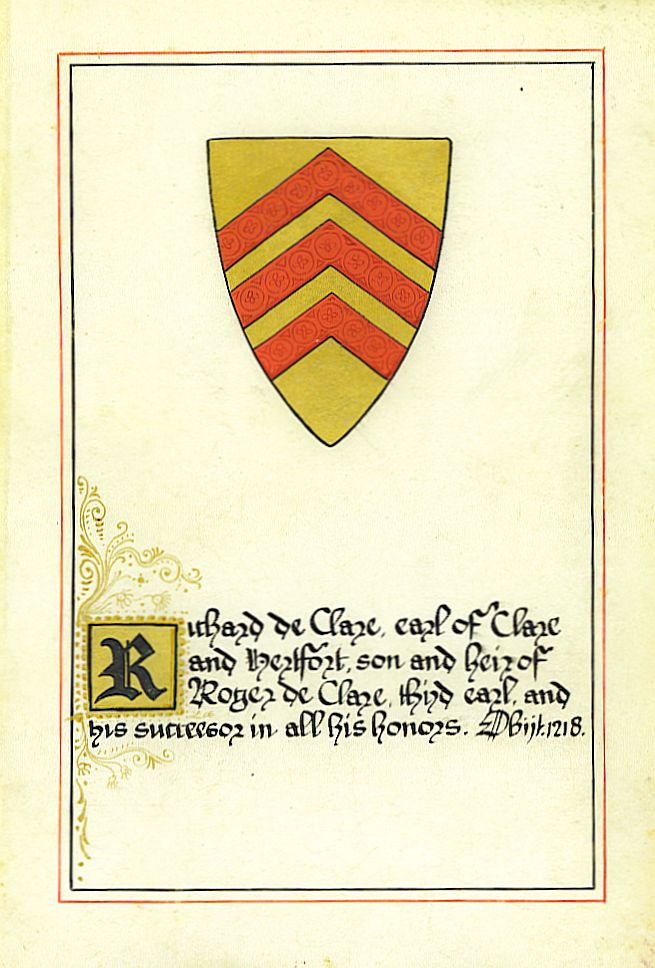

Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford.

Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Hertford (August 4, 1222 – July 15, 1262) was son of Gilbert de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford and Isabel Marshall, daughter of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke and Isabel de Clare, the 17-year-old daughter of Strongbow. A year after he became of age, he was in an expedition against the Welsh. Through his mother he inherited a fifth part of the Marshall estates, including Kilkenny and other lordships in Ireland. In 1232 Richard was secretly married to Margaret (Megotta) de Burgh, daughter of Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent and Margaret of Scotland. Both bride and groom were aged about ten. Megotta died in November 1237. Before she had even died, the earl of Lincoln offered 5,000 marks to King Henry to secure Richard for his own daughter. This offer was accepted, and Richard was married secondly, on or before 25 January 1238, to Maud de Lacy, daughter of the Surety John de Lacy and Margaret Quincy. He joined in the Barons’ letter to the Pope in 1246 against the exactions of the Curia in England. He was among those in opposition to the King’s half-brothers, who in 1247 visited England, where they were very unpopular, but afterwards he was reconciled to them. On April 1248, he had letters of protection for going over seas on a pilgrimage. At Christmas 1248, he kept his Court with great splendor on the Welsh border. In the next year he went on a pilgrimage to St. Edmund at Pontigny, returning in June. In 1252 he observed Easter at Tewkesbury, and then went across the seas to restore the honor of his brother William, who had been badly worsted in a tournament and had lost all his arms and horses. The Earl is said to have succeeded in recovering all, and to have returned home with great credit, and in September he was present at the Round Table tournament at Walden. In August 1252/3 the King crossed over to Gascony with his army, and to his great indignation the Earl refused to accompany him and went to Ireland instead. In August 1255 he and John Maunsel were sent to Edinburgh by the King to find out the truth regarding reports which had reached the King that his son-in-law, Alexander, King of Scotland, was being coerced by Robert de Roos and John Baliol. If possible, they were to bring the young King and Queen to him. The Earl and his companion, pretending to be the two of Roos’s knights, obtained entry to Edinburgh Castle, and gradually introduced their attendants, so that they had a force sufficient for their defense. They gained access to the Scottish Queen, who made her complaints to them that she and her husband had been kept apart. They threatened Roos with dire punishments, so that he promised to go to the King. Meanwhile the Scottish magnates, indignant at their castle of Edinburgh’s being in English hands, proposed to besiege it, but they desisted when they found they would be besieging their King and Queen. The King of Scotland apparently traveled South with the Earl, for on 24 September they were with King Henry III at Newminster, Northumberland. In July 1258 he fell ill, being poisoned with his brother William, as it was supposed, by his steward, Walter de Scotenay. He recovered but his brother died. Richard died at John de Griol’s manor of Asbenfield in Waltham, near Canterbury, 15 July 1262, it being rumored that he had been poisoned at the table of Piers of Savoy. On the following Monday he was carried to Canterbury where a mass for the dead was sung, after which his body was taken to the canon’s church at Tonbridge and interred in the choir. Thence it was taken to Tewkesbury Abbey and buried 28 July 1262, with great solemnity in the presence of two bishops and eight abbots in the presbytery at his father’s right hand.

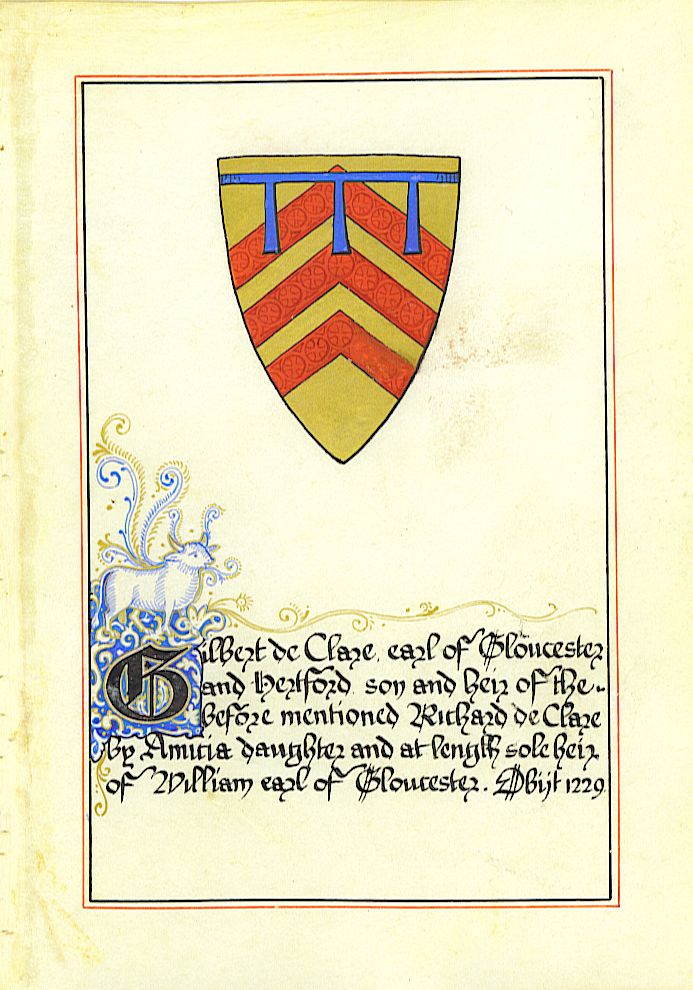

Gilbert de Clare, heir to the earldom of Hertford.

Gilbert de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford (1180 – October 25, 1230) was the son of Richard de Clare, 4th Earl of Hertford, from whom he inherited the Clare estates, from his mother, Amice Fitz William, the estates of Gloucester and the honour of St. Hilary, and from Rohese, an ancestor, the moiety of the Giffard estates. In June 1202, he was entrusted with the lands of Harfleur and Montrevillers. In 1215 Gilbert and his father were two of the barons made Magna Carta sureties and championed Louis “le Dauphin” of France in the First Barons’ War, fighting at Lincoln under the baronial banner. He was taken prisoner in 1217 by William Marshal, whose daughter Isabel he later married. In 1223 he accompanied his brother-in-law, Earl Marshal, in an expedition into Wales. In 1225 he was present at the confirmation of the Magna Carta by Henry III. In 1228 he led an army against the Welsh, capturing Morgan Gam, who was released the next year. He then joined in an expedition to Brittany, but died on his way back to Penrose in that duchy. His body was conveyed home by way of Plymouth and Cranborne to Tewkesbury. His widow Isabel later married Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cornwall & King of the Romans.

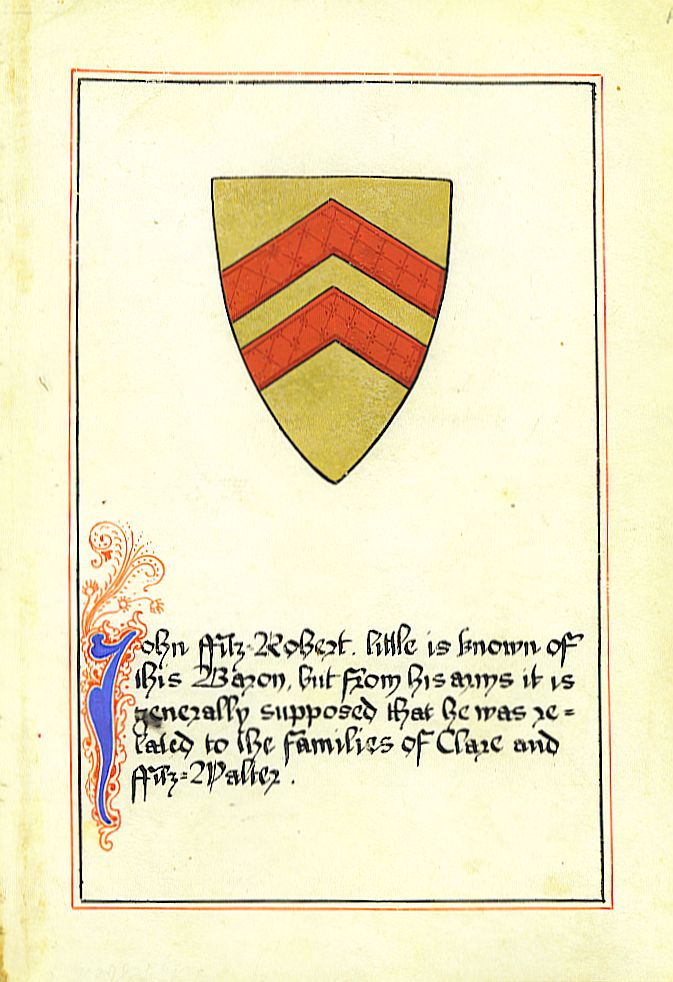

John FitzRobert, Lord of Warkworth Castle.

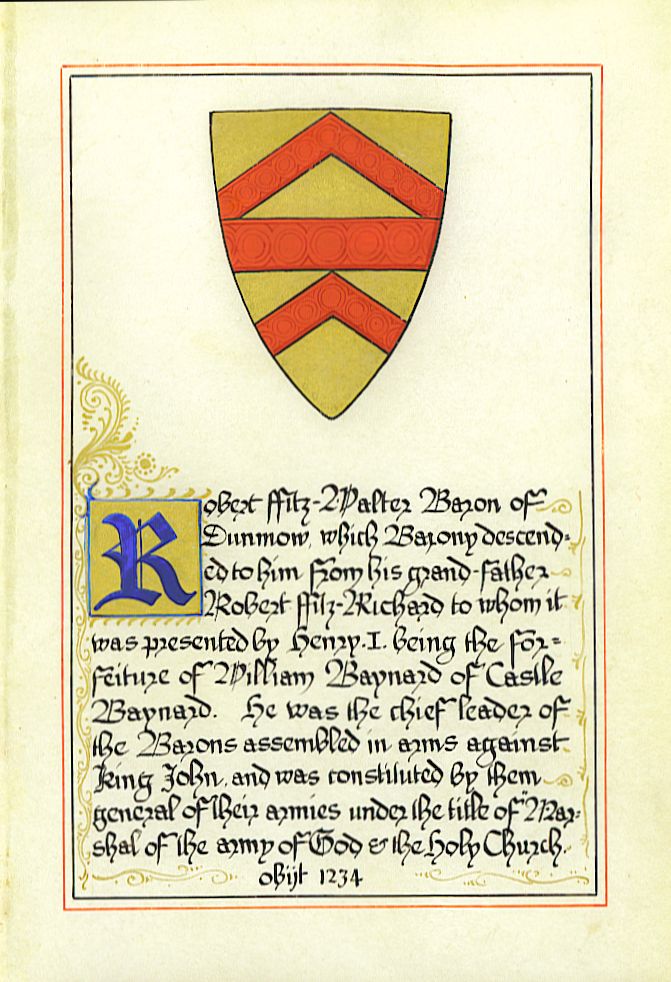

Robert Fitzwalter, Lord of Dunmow Castle.

Lord Robert Fitzwalter (died 9 December 1235), leader of the baronial opposition against King John of England, belonged to the official aristocracy created by Henry I and Henry II. He was one of the twenty-five Magna Charta Sureties. He was the third Lord of Dunmow Castle, Essex. He was son to Walter Fitz Robert of Woodham Walter and his second wife Maud de Lucy, daughter of Richard de Lucy of Diss. Contents

He served John in the Norman wars, and was taken prisoner by Philip II of France, and forced to pay a heavy ransom. He was implicated in the baronial conspiracy of 1212. According to his own statement the king had attempted to seduce his eldest daughter; but Robert’s account of his grievances varied from time to time. The truth seems to be that he was irritated by the suspicion with which John regarded the new baronage. Fitzwalter escaped a trial by fleeing to France. He was outlawed, but returned under a special amnesty after John’s reconciliation with Pope Innocent III. He continued, however, to take the lead in the baronial agitation against the king, and upon the outbreak of hostilities was elected marshal of the army of God and Holy Church (1215). It was due to his influence in London that his party obtained the support of the city and used it as their base of operations. The famous clause of Magna Carta prohibiting sentences of exile except as the result of a lawful trial refers more particularly to his case. He was one of the twenty-five appointed to enforce the promises of Magna Carta and his aggressive attitude was one of the causes which contributed to the recrudescence of civil war (1215). His incompetent leadership made it necessary for the rebels to invoke the help of France. He was one of the envoys who invited Louis to the Kingdom of England, and was the first of the barons to do homage when the prince entered London. Though slighted by the French as a traitor to his natural lord, he served Louis with fidelity until captured at the Battle of Lincoln on 20 May 1217. Released on the conclusion of peace, Fitzwalter joined the Fifth Crusade (1217 – 1221), but returned at an early date to make his peace with the regency. The remainder of his career was uneventful; he died peacefully in 1235.

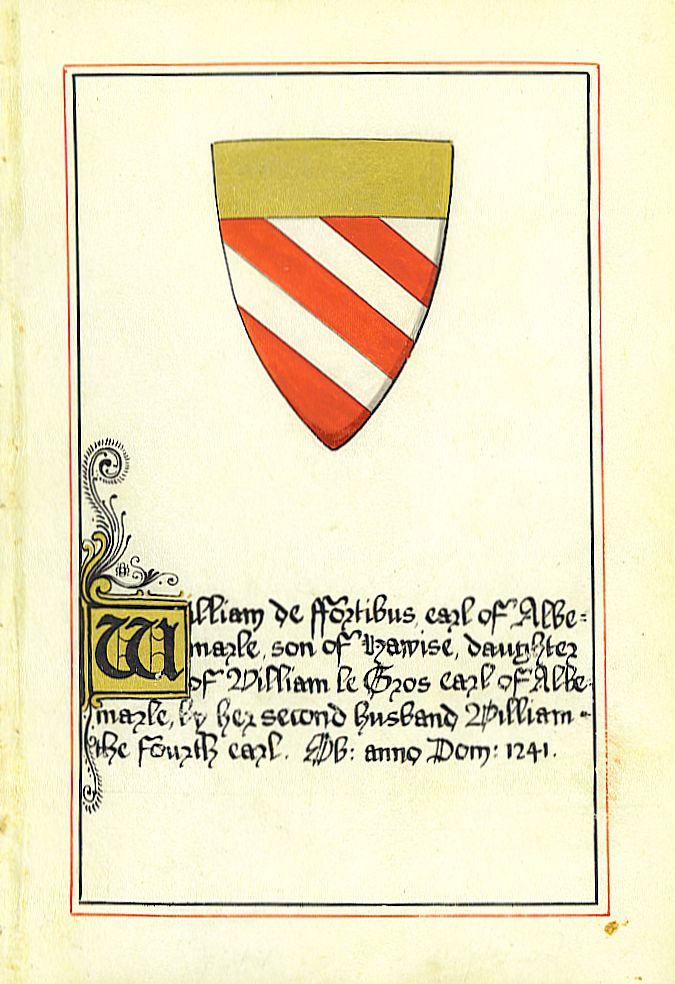

William de Fortibus, Earl of Albemarle.

William de Forz, 3rd Earl of Albemarle (died March 26, 1242) was an English nobleman. He is described by William Stubbs as “a feudal adventurer of the worst type”. He was the son of William de Forz (died 1195), and Hawisa, 2nd Countess of Albemarle, a daughter of William le Gros, 1st Earl of Albemarle. His father was a minor noble from the village of Fors in Poitou; the toponymic is variously rendered as de Fors, de Forz, or de Fortibus. Soon after 1213, he was established by King John in the territories of the Countship of Albemarle, and in 1215 the whole of his mother’s estates were formally confirmed to him. The Earldom of Albemarle which he inherited from his mother included a large estate in Yorkshire, notably the wapentake of Holderness and the castle of Skipsea, and the honor of Craven, as well as property in Lincolnshire and elsewhere. It had also included the county of Aumale, but this had recently been lost to the French, along with the rest of Normandy. De Forz was the first earl of Albemarle to see his earldom as wholly English. He was actively engaged in the struggles of the Norman barons against both John and Henry III. He was generally loyal to King John during the baronial revolt, though he did eventually join the barons after the people of London joined them and the king’s cause looked hopeless. He was one of the 25 executors of the Magna Carta, but amongst them was probably the least hostile to the king. The barons made de Forz constable of Scarborough Castle, but when soon after fighting began between the barons and the king, he went over to John’s side, the only executor to do so. He fought for the king until the French capture of Winchester in June 1216, when again the king’s cause looked hopeless. He then stayed on the barons side until their cause fell apart. He sided with John, then subsequently changing sides as often as it suited his policy. After John’s death, he supported the new king Henry III, fighting in the siege of Montsorrel and at the Battle of Lincoln. His real object was to revive the independent power of the feudal barons, and he co-operated to this end with Falkes de Breauté and other foreign adventurers established in the country by John. This brought him into conflict with the great justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, who was effectively regent. In 1219 he was declared a rebel and excommunicated for attending a forbidden tournament. In 1220 matters were brought to a crisis by his refusal to surrender the two royal castles of Rockingham and Sauvey of which he had been made constable in 1216. Henry III marched against them in person, the garrisons fled, and they fell without a blow. In the following year, however, Albemarle, in face of further efforts to reduce his power, rose in revolt. He was now again excommunicated by the legate Pandulph at a solemn council held in St Paul’s, and the whole force of the kingdom was set in motion against him, a special scutage—the scutagium de Bihan—being voted for this purpose by the Great Council. The capture of his Castle of Bytham broke his power; he sought sanctuary and, at Pandulph’s intercession, was pardoned on condition of going for six years to the Holy Land. He remained in England, however, and in 1223 was once more in revolt with Falkes de Breauté, the Earl of Chester and other turbulent spirits. A reconciliation was once more patched up; but it was not until the fall of Falkes de Breauté that Albemarle finally settled down as an English noble. He eventually gave in when the cause was lost in 1224, and was thenceforth loyal to Henry III. In 1225 he witnessed Henry’s third re-issue of the Great Charter; in 1227 he went as, ambassador, to Antwerp; and in 1230 he accompanied Henry on his expedition to Brittany. In 1241 he set out for the Holy Land, but died at sea, on his way there, on March 26 1242.

William Hardel, Mayor of the City of London.

William de Huntingfield, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk.

William of Huntingfield (c.1165-1220/1) was an English sheriff in Norfolk and Suffolk and landowner, and one the Magna Carta sureties. He held Dover Castle from 1204 and in the First Barons’ War, and was an active rebel against John of England. He married Isabel Fitz Roger, daughter of William Fitz Roger. He subsequently supported the French invasion of England, and took part in the Fifth Crusade, where he died

John de Lacy, Lord of Pontefract Castle.

John de Lacy (c. 1192 – 1240) was the 1st Earl of Lincoln, of the fifth creation. He was the eldest son and heir of Roger de Lacy and his wife, Maud or Matilda de Clere (not of the de Clare family). In 1221 he married Margaret de Lacy, daughter of Robert de Quincy and niece of Ranulph de Blondeville through her mother Hawise. Through this marriage John was in 1232 allowed to succeeded de Blondeville as earl of Lincoln. He was one of twenty-five barons charged with overseeing the observance of Magna Carta in 1215. He was hereditary constable of Chester and,in the 15th year of King John, undertook the payment of 7,000 marks to the crown, in the space of four years, for livery of the lands of his inheritance, and to be discharged of all his father’s debts due to the exchequer, further obligating himself by oath, that in case he should ever swerve from his allegiance, and adhere to the king’s enemies, all of his possessions should devolve upon the crown, promising also, that he would not marry without the king’s license. By this agreement it was arranged that the king should retain the castles of Pontefract and Dunnington, still in his own hands; and that he, the said John, should allow 40 pounds per year, for the custody of those fortresses. But the next year he had Dunnington restored to him, upon hostages. About this period he joined the baronial standard, and was one of the celebrated twenty-five barons, one of the Sureties, appointed to enforce the observance of the Magna Charta. But the next year, he obtained letters of safe conduct to come to the king to make his peace, and he had similar letters, upon the accession of Henry III., in the second year of which monarch’s reign, he went with divers other noblemen into the Holy Land. John de Lacy (Lacie), 7th Baron of Halton Castle, and hereditary constable of Chester, was one of the earliest who took up arms at the time of the Magna Charta, and was appointed to see that the new statutes were properly carried into effect and observed in the counties of York and Nottingham. He was excommunicated by the Pope. Upon the accession of King Henry III. he joined a party of noblemen and made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and did good service at the siege of Damietta. In 1232 he was made Earl of Lincoln and in 1240, governor of Chester and Beeston Castles. He died July 22, 1240, and was buried at the Cisterian Abbey of Stanlaw, in co. Chester. The monk Matthew Paris, records: “On the 22nd day of July, in the year 1240, which was St. Magdalen’s Day, John, Earl of Lincoln, after suffering from a long illness went the way of all flesh.” He married Alice, daughter of Gilbert de Aquila, but by her had no issue. She died in 1215 and, after his marked gallantry at the siege of Damietta, he married (2) Margaret Quincy only daughter and heir of Robert de Quincy, Earl of Winchester, by Hawyse, 4th sister and co-heir of Ranulph de Mechines, Earl of Chester and Lincoln , which Ranulph, by a formal charter under his seal, granted the Earldom of Lincoln, that is, so much as he could grant thereof, to the said Hawyse, “to the end that she might be countess, and that her heirs might also enjoy the earldom;” which grant was confirmed by the king, and at the especial request of the countess, this John de Lacy, constable of Chester, was created by charter, dated Northampton, November 23, 1232, Earl of Lincoln, with remainder to the heirs of his body, by his wife, the above-mentioned Margaret. In the contest which occurred during the same year, between the king and Richard Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, Earl Marshal, Matthew Paris states that the Earl of Lincoln was brought over to the king’s party, with John le Scot, Earl of Chester, by Peter de Rupibus, Bishop of Winchester, for a bribe of 1,000 marks. In 1237, his lordship was one of those appointed to prohibit Oto, the pope’s prelate, from establishing anything derogatory to the king’s crown and dignity, in the council of prelates then assembled; and the same year he had a grant of the sheriffalty of Cheshire, being likewise constituted Governor of the castle of Chester. The earl died in 1240, leaving Margaret, his wife, surviving, who remarried William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke.

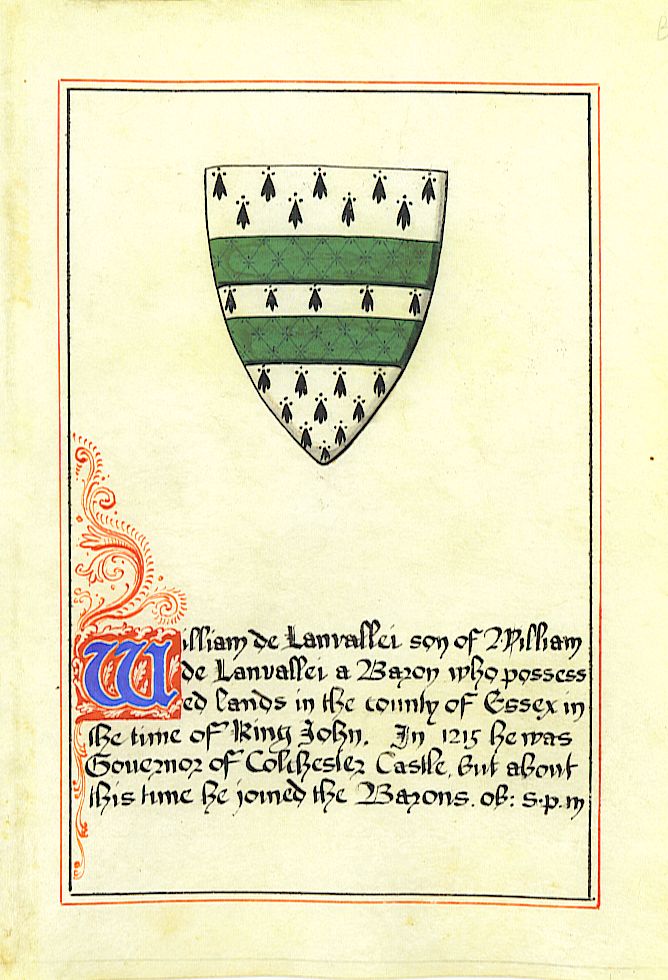

William de Lanvallei, Lord of Standway Castle.

William Malet, Sheriff of Somerset and Dorset.

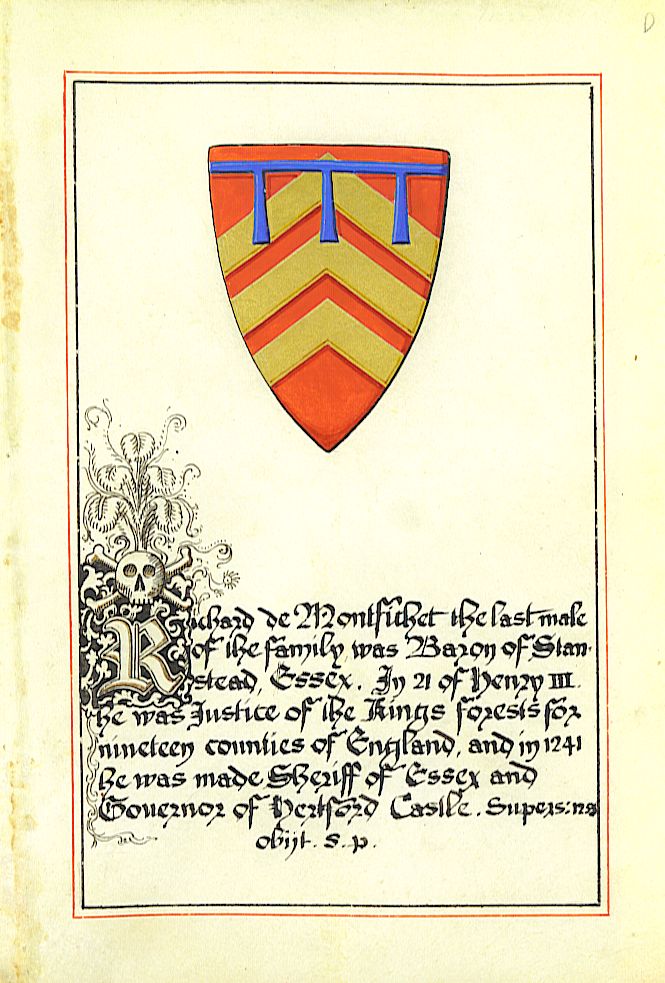

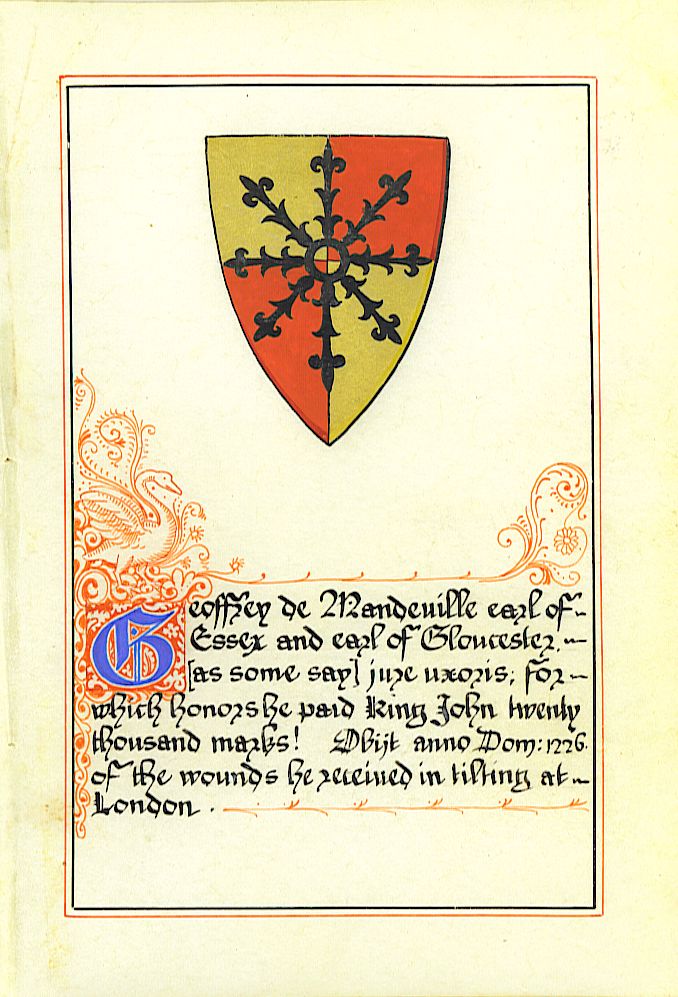

Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester.

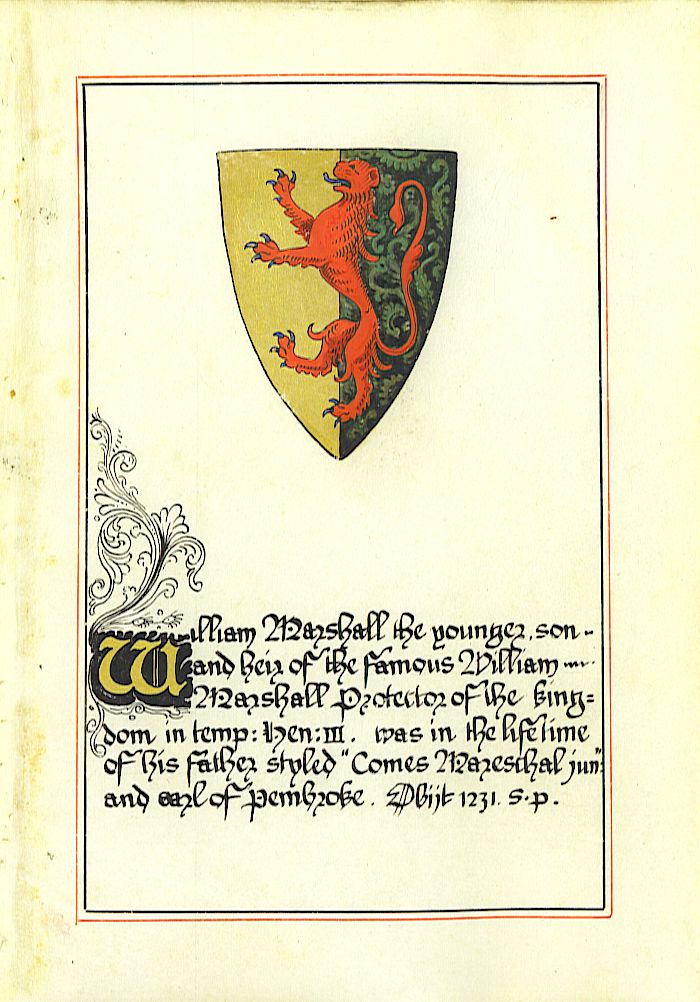

William Marshall Jr, heir to the earldom of Pembroke.

William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1190 – April 6, 1231) was a medieval English nobleman, and the son of the famous William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke.

William was born in Normandy probably during the winter of 1190/91. From 1205 to 1212, he was at the court of King John as a guarantee of his father’s behaviour. William married Alice de Bethune, daughter of his father’s friend Baldwin de Bethune, in September 1214. The marriage ended before 1215 when Alice was murdered while heavily pregnant with William’s Son,who died as well. During the baronial rebellion of 1215, William was on the side of the rebels while his father was fighting for the king. When Louis of France took Worcester castle in 1216, however, the younger William was warned by his father to withdraw, which he did just before Ranulph de Blondeville, 4th Earl of Chester retook the castle. In March 1217, he was absolved from excommunication and rejoined the royal cause. At the Battle of Lincoln he was fighting with his father.

At his father’s death in 1219 he succeeded the elder William as both Earl of Pembroke and as Lord Marshal of England. These two powerful titles, combined with his father’s legendary status, could not help but make William one of the most prominent and powerful nobles in England. In 1224, William married Eleanor of England, youngest daughter of King John and Isabella of Angouleme, thereby strengthening the family’s connection with the Plantagenets. In 1223, William crossed over from his Irish lands to campaign against Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, who had attacked his holding of Pembroke. He was successful, but his actions were seen as too independent by the young Henry III’s regents. In 1226 he was ordered to surrender the custody of the royal castles of Cardigan and Carmarthen, that he had captured from Llywelyn, to the crown. The same year, Hugh de Lacy began attacking William’s and the King’s lands in Ireland. William was appointed justiciar of Ireland, and managed to subdue Hugh. William accompanied the king to Brittany in 1230, and assumed control of the forces when the king returned to England. Then, in February 1231, William also returned to England. Here he arranged the marriage of his sister Isabel, widow of Gilbert de Clare, to Richard, Earl of Cornwall, brother to King Henry III. William died in April of the same year. Matthew Paris claims that Hubert de Burgh, justiciar of England, was later accused of poisoning William, but there are no other sources to support this.

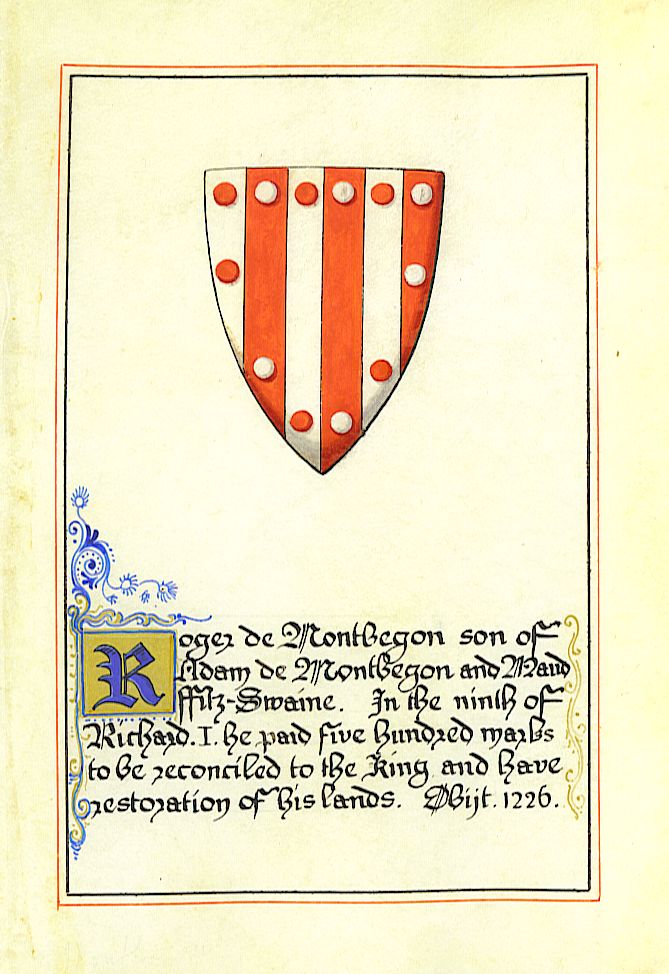

Roger de Montbegon, Lord of Hornby Castle, Lancashire.

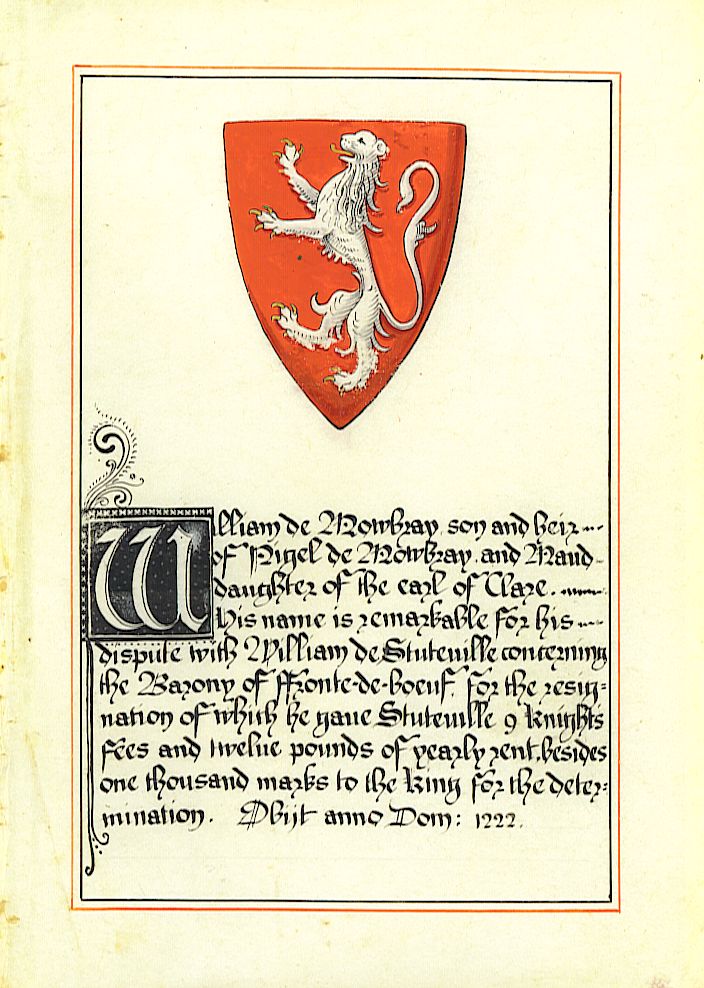

William de Mowbray, Lord of Axholme Castle.

Mowbray , the name of an Anglo-Norman baronial house, derived from Montbray (Manche) in Normandy south of St Lo. The heraldic badge of the house was a mulberry tree. It was founded at the Conquest by Geoffrey de Montbray, bishop of Coutances. His brother’s son Robert de Montbray, who rebelled with him against William Rufus on the Conqueror’s death, was made, after their reconciliation, earl of Northumbria, as his uncle’s heir but was forfeited and imprisoned for life on rebelling again in 1095. Roger d’Aubigny (of Aubigny in the Cotentin) had two sons, Nigel and William, who were ardent supporters of Henry I. They were rewarded by him with great estates in England. William was made king’s butler, and was father of William d’Aubigny (de Albini), first earl of Arundel; Nigel was rewarded with the escheated fief of Robert de Montbray in Normandy and a number of lands in England. Nigel married, by dispensation, the wife of Robert de Montbray, the imprisoned earl, but afterwards divorced her, and by another wife was father of a son Roger, who took the name of Mowbray. Roger, a great lord with a hundred knight’s fees, was captured with King Stephen at the battle of Lincoln, joined the rebellion against Henry II (1173), founded abbeys, and went on crusade. His grandson William, a leader in the rising against King John, was one of the 25 barons of the Great Charter, as was his brother Roger, and was captured fighting against Henry III at the rout of Lincoln (1217). William’s grandson Roger (1266-1298), who was summoned to parliament by Edward I, was father of John (1286-1322), a warrior and warden of the Scottish March, who, joining in Thomas of Lancaster’s revolt, was captured at Boroughbridge and hanged. His wife, a Braose heiress, added Gower in South Wales and the Bramber lordship in Sussex to the great possessions of his house. Their son John de Mowbray, 3rd Baron Mowbray (d. 1361) was father, by Joan of Lancaster, a daughter of Henry Plantagenet, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, of John, Lord Mowbray (c. 1328-1368), whose fortunate alliance with the heiress of John de Segrave, 4th Baron Segrave, by the heiress of Edward I’s son Thomas, earl of Norfolk and marshal of England, crowned the fortunes of his race. In addition to a vast accession to their lands, the earldom of Nottingham and the marshalship of England were bestowed on them by Richard II, and the dukedom of Norfolk followed. The 1st duke left two sons, of whom Thomas the elder was only recognized as earl marshal. Beheaded for joining in Scrope’s conspiracy against Henry IV (1405), he was succeeded by his brother John, who was restored to the dukedom of Norfolk in 1424. His son John, the third duke, was father of John, 4th and last duke, who was created earl of Warrenne and Surrey in his father’s lifetime (1451). At his death (14l8) his vast inheritance devolved on his only child Anne, who was married as an infant to Edward IV’s younger son Richard (created duke of Norfolk and earl of Nottingham and Warrenne), but died in 1481. The next heirs of the Mowbrays were then the Howards and the Berkeleys, representing the two daughters of the first duke. Between them were divided the estates of the house, the Mowbray dukedom of Norfolk and earldom of Surrey being also revived for the Howards (1483), and the earldom of Nottingham (1483) and earl marshalship (1485) for the Berkeleys. Both families assumed the baronies of Mowbray and Segrave, but Henry Howard was summoned in his father’s lifetime (1640) as Lord Mowbray, which was deemed a recognition of the Howards’ right; their co-heirs, from 1777, were the Lords Stourton and the Lords Petre, and in 1878 Lord Stourton was summoned as Lord Mowbray and Segrave. The former dignity is claimed as the premier barony, though De Ros ranks before it. Lord Stourton’s son claimed, but unsuccessfully, in 1901-1906 the earldom of Norfolk (1312), also through the Mowbrays. Of the Mowbray estates the castle and lordship of Bramber is still vested in the dukes of Norfolk.

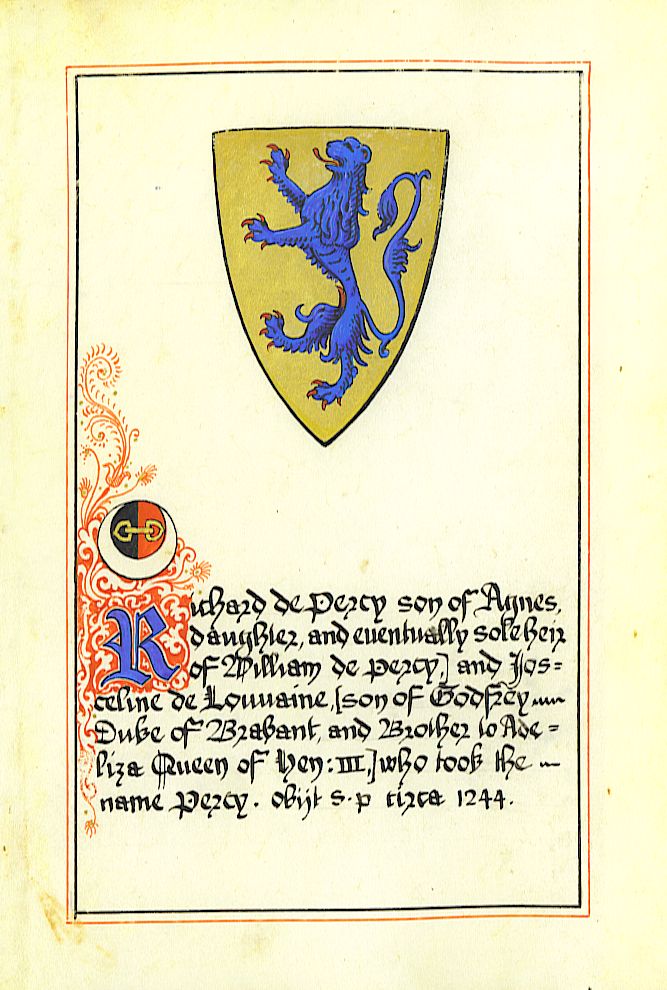

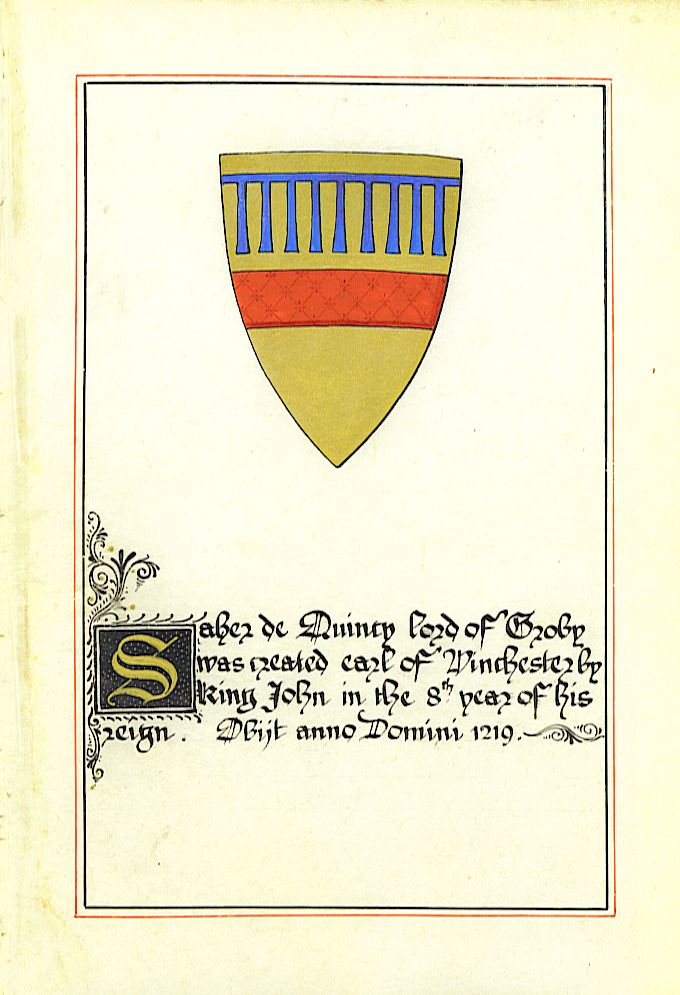

Saire/Saher de Quincy, Earl of Winchester.

Saer de Quincy, 1st Earl of Winchester (1155 – 1219-11-03) was one of the leaders of the baronial rebellion against King John of England, and a major figure in both Scotland and England in the decades around the turn of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Saer de Quincy’s immediate background was in the Scottish kingdom: his father was a knight in the service of king William the Lion, and his mother was the heiress of the lordship of Leuchars in Fife (see below). His rise to prominence in England came through his marriage to Margaret, the younger sister of Robert de Beaumont, 4th Earl of Leicester: but it is probably no coincidence that her other brother was the de Quincys’ powerful Fife neighbour, Roger de Beaumont, Bishop of St Andrews. In 1204, Earl Robert died, leaving Margaret as co-heiress of the vast earldom along with her elder sister. The estate was split in half, and after the final division was ratified in 1207, de Quincy was made Earl of Winchester. Following his marriage, de Quincy became a prominent military and diplomatic figure in England. There is no evidence of any close alliance with King John, however, and his rise to importance was probably due to his newly-acquired magnate status and the family connections that underpinned it. One man with whom he does seem to have developed a close personal relationship is his cousin, Robert Fitzwalter. They are first found together in 1203, as co-commanders of the garrison at the major fortress of Vaudreuil in Normandy; they were responsible for surrendering the castle without a fight to Philip II of France, fatally weakening the English position in northern France, but although popular opinion seems to have blamed them for the capitulation, a royal writ is extant stating that the castle was surrendered at King John’s command, and both Saer and Fitzwalter had to endure personal humiliation and heavy ransoms at the hands of the French. In Scotland, he was perhaps more successful. In 1211-12, the Earl of Winchester commanded an imposing retinue of a hundred knights and a hundred serjeants in William the Lion’s campaign against the Mac William rebels, a force which some historians have suggested may have been the mercenary force from Brabant lent to the campaign by John. In 1215, when the baronial rebellion broke out, Robert Fitzwalter became the military commander, and the Earl of Winchester joined him, acting as one of the chief negotiators with John; both cousins were among the 25 guarantors of the Magna Carta. De Quincy fought against John in the troubles that followed the signing of the Charter, and, again with Fitzwalter, travelled to France to invite Prince Louis of France to take the English throne. He and Fitzwalter were subsequently among the most committed and prominent supporters of Louis’ candidature for the kingship, against both John and the infant Henry III. When military defeat cleared the way for Henry III to take the throne, de Quincy went on crusade, perhaps in fulfillment of an earlier vow, and in 1219 he left to join the Fifth Crusade, then besieging Damietta. While in the east, he fell sick and died. He was buried in Acre, the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, rather than in Egypt, and his heart was brought back and interred at Garendon Abbey near Loughborough, a house endowed by his wife’s family.

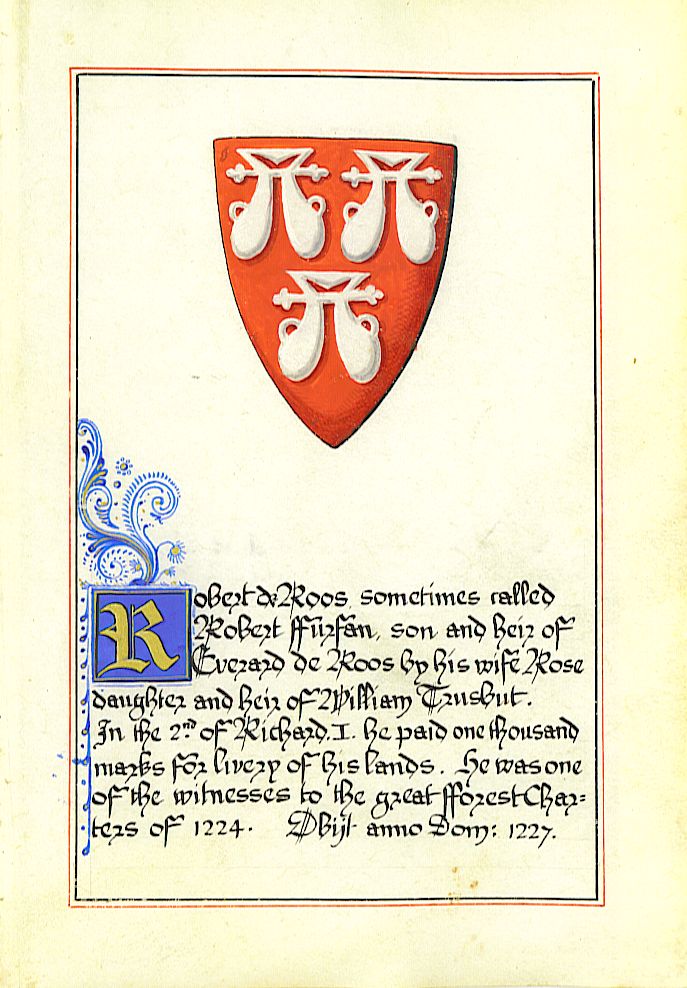

Robert de Roos, Lord of Hamlake Castle.

Sir Robert de Ros or Roos of Fursan (1177 – 11 December 1226) was the fourth baron by tenure of Hamlake manor (later associated with the barony of de Ros). He was the son of Everard de Ros and Rose Trusbut. In 1191, aged fourteen, he paid a thousand marks fine for livery of his lands to King Richard I of England. Also that year, he married Isabel, sister (or possibly daughter) of William the Lion, King of Scots (Isabella not to be confused with William I’s daughter Isabella who married Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk). In 1197, while serving King Richard in Normandy, he was arrested for an unspecified offence, and was committed to the custody of Hugh de Chaumont, but Chaumont entrusted his prisoner to William de Spiney, who allowed him to escape from the castle of Bonville. King Richard thereupon hanged Spiney and collected a fine of twelve hundred marks from Ros’ guardian as the price of his continued freedom. When King John came to the throne, he gave Ros the barony of his great-grandmother’s father, Walter d’Espec. Soon afterwards he was deputed one of those to escort William the Lion, his brother-in-law, into England, to swear fealty to King John. Some years later, Robert de Ros assumed the habit of a monk, whereupon the custody of all his lands and Castle Werke, in Northumberland, were committed to Philip d’Ulcote, but he soon returned and about a year later he was High Sheriff of County Cumberland. When the struggle of the barons for a constitutional government began, de Ros at first sided with King John, and thus obtained some valuable grants from the crown, and was made governor of Carlisle; but he subsequently went over to the barons and became one of the celebrated twenty-five “Sureties” appointed to enforce the observance of Magna Carta, the county of Northumberland being placed under his supervision. He gave his allegiance to King Henry III and, in 1217-18, his manors were restored to him. Although he was witness to the second Great Charter and the Forest Charter, of 1224, he seems to have remained in royal favour.

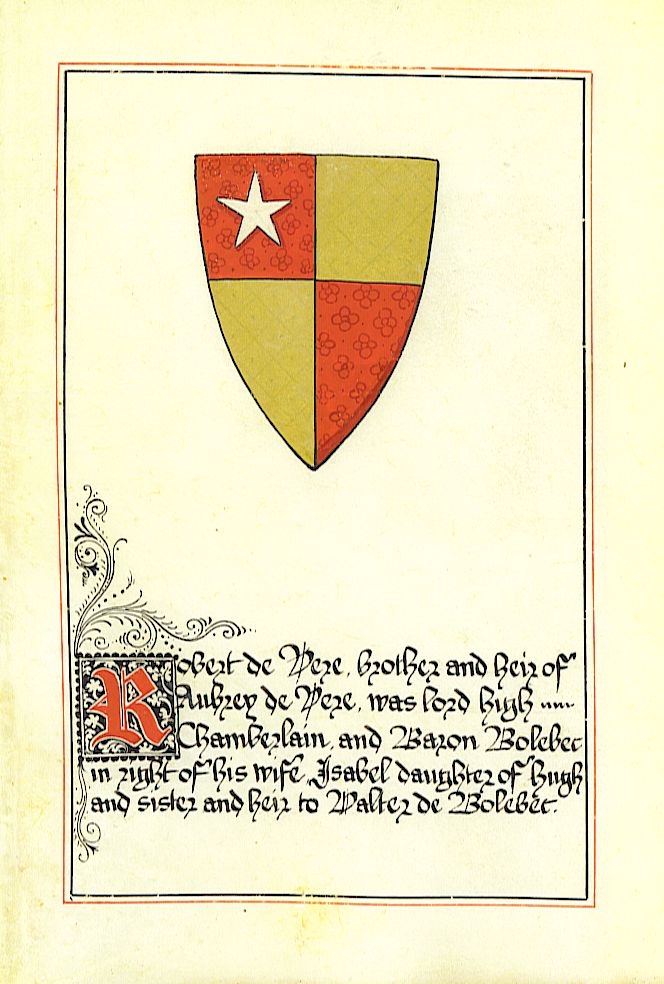

Robert de Vere, heir to the earldom of Oxford.

Robert de Vere (died 1221) was the second surviving son of Aubrey de Vere III, first earl of Oxford, and Agnes of Essex. Almost nothing of his life is known until he married in 1207 the widow Isabel de Bolebec, the aunt and co-heiress of his deceased sister-in-law. The couple had one child, a son, Hugh, later 4th earl of Oxford. When Robert’s brother Aubrey de Vere IV, 2nd earl of Oxford died in Oct. 1214, Robert succeeded to his brother’s title, estates, castles, and hereditary office of master chamberlain of England (later Lord Great Chamberlain). He swiftly joined the disaffected barons in opposition to King John; many among the rebels were his kinsmen. He was elected one of the twenty-five barons who were to ensure the king’s adherence to the terms of Magna Carta, and as such was excommunicated by Pope Innocent III in 1215. King John besieged and took Castle Hedingham, Essex, from Robert in March 1216 and gave his lands to a loyal baron. While this prompted Robert to swear loyalty to the king soon thereafter, he nonetheless did homage to Prince Louis when the French prince arrived in Rochester later that year. He remained in the rebel camp until Oct. 1217, when he did homage to the boy-king Henry III, but he was not fully restored in his offices and lands until Feb. 1218. At this time, aristocratic marriages were routinely contracted after negotiations over dowry and dower. In most cases, dower lands were assigned from the estates held by the groom at the time of the marriage. If specific dower lands were not named, on the death of the husband the widow was entitled to one-third of his estate. When Robert’s brother Earl Aubrey married a second time, he did not name a dower for his wife Alice, for Robert determined the division of his estate by having lots drawn. For each manor his sister-in-law drew, he drew two. This is the sole known case of assigning dower lands in this manner. Robert served as a king’s justice in 1220-21, and died in Oct. 1221. He was buried at Hatfield Regis Priory, where his son Earl Hugh or grandson Earl Robert later had an effigy erected. Earl Robert is depicted in chain mail, cross-legged, pulling his sword from its scabbard and holding a shield with the arms of the Veres.