Paul Kersten’s Decorative Leather Work

By Octave Uzanne

THE decorative arts have assumed considerable importance of late years in Germany, and during the recent Paris International Exhibition it came somewhat as a surprise to find, in the German sections of goldsmith’s work, pottery, furniture, etc., evidence of real progress in industrial art on the part of those who hitherto had certainly not been distinguished for good taste and decorative harmony.

Germany now takes a foremost place among the nations who are striving to create new forms of decorative art designed to embellish life by means of the ornamentation of the dwelling-house and its furniture. The advance made in respect of pewter-work, jewellery, faience, and porcelain was well known and generally recognised, but the Germans were held to be behind England, France, Belgium, and certain Scandinavian centres in the matter of artistic binding. All we knew was that interesting and curious experiments had been made by Voigt and Collin, of Berlin, by Graf at Altenbourg, and by Scholl at Durlach : but in none of these instances was there evidence of actual novelty, of ornamental initiative likely to be crowned by success.

There seemed in all this work to be too much heaviness, too much of the past, too great a confusion of styles, too little spontaneity and invention. These productions were rich, but laboured, and overcharged with ornament, and despite their admirable workmanship, which was absolutely perfect from the technical point of view, the touch of real art was invariably lacking, and they remained bastard art at best, bereft as they were of the penetrating beauty, the original and captivating grace inseparable from work inspired by genius from within.

Since then, schools of binding, ornamentation and gilding have been established in Germany, notably those of Otto Horn, Wilhelm Patizelt, and Alfred Kullmann. Here intelligent and devoted teachers inculcated to hundreds of hard-working students the principles of art as applied to leather; they taught the esthetics of binding, expounded the difficulties of gilding on morocco, and aroused a sense of curiosity as to new decorative motto, always going straight to Nature for inspiration, and carefully considering the demands of the space to be ornamented ; finally they were careful to insist on the irreconcilable difference between true art binding and the Paccotille morocco work, which too long burdened the German market with its exaggerated floral graces and lavish gilding.

Gradually an improvement was apparent in the productions of the leading binders, who had taken advantage of the practical knowledge acquired by certain students who had distinguished themselves at the new schools. Thus a steady renovation set in, which, young as it is, cannot be overlooked ; and there can be no doubt that ten or a dozen years hence German art binding will command universal admiration, if as there is every reason to hope, students of the highest ability continue to appear as rivals of the existing master-binders of England and France.

Truth to tell, it is not at the present moment the French binders– the Rubns, the Marius-Michels, or the Charles Meuniers—who apppear to be influencing their German confreres. The symbolical styles of the French craftsmen, and their mosaics, aiming at pictorial effect, are rarely copied ; the methods of Cobden-Sanderson, Riviere, Zaensdorff, and Miss E. M. MacColl appear to have struck the fancy of the German morocco workers. These are largely based on the style of the Italian masters of the sixteenth century, with supple and elegant interlacings, infinite in their combinations. This return to the primitive fashion is very fascinating, the maximum of effect being often obtained by means of the fewest possible motifs.

The bindings of Mr. Paul Kersten, who has been established for a short time at Aschaffenbourg, and displayed some very fine examples of his work at the recent International Art Exhibition at Dresden, are the most striking manifestation yet made by the young German school of binding. He shines especially as a gilder. After a long course of work for a big firm at Leipzig, under the management of M. Sperling, for whom he did his earliest bindings, Paul Kersten was confident enough to start on his own account, in order to bring his name before the public and do justice to his signature.

He should have no cause to regret this act of independence and legitimate pride, for it is to be hoped German bibliophiles will all go to him; and doubtless France and England will demand from him specimens of his masterly productions. He is now on the high-road to success, and it is only right that attention should be drawn to his curious and restrained method of decorating morocco.

Mr. Paul Kersten is not only a most skilful practitioner of his art, but a subtle theorician thereon – one might say an apostle. I remember to have read a few years ago in some German magazine a certain “Causerie d’un specialiste,” by Mr. Kersten, which showed that he possessed a very clear and very acute sense of his subject.

After having plainly and concisely demonstrated the proper method of making an artistic binding, which should combine the double result of technical beauty and a:sthetic harmony, Mr. Kersten endeavoured to show that German binding was in no way inferior, either decoratively or as sheer workmanship, to French binding. I cannot go so far as to say his demonstration was conclusive; he seemed to ignore much of the work of contemporary binders well known in Paris and in London.

At any rate, he was absolutely honest in his conviction. Having dealt with the technical side of the question, Mr. Kersten, in the article already mentioned, treated of its historical aspect from the fifteenth century, revealing abundant erudition and a remarkable knowledge of all his predecessors in all the countries of Europe. He traced back the introduction of art binding into Germany – that is to say, bindings with gilding on leather – to the middle of the sixteenth century only.

According to him, its origin was Venetian and the introducers were the Frankfort libraires, who at each annual fair sold a great number of books printed in Venice, partly by learned German monks such as Mutianus Rufus, of the monastery of Georgenthal, who sent to their native country many admirable books wholly bound. In any case, the cradle of German, or, to be more exact, of Saxon binding, was the University of Wittenberg, founded in 1502 by the Elector Frederic the Good.

Having awarded full praise to the heavy leather covers of the bouquins of the seventeenth century, Mr. Kersten has to admit that the eighteenth century produced nothing but copies of French bindings ; and, further, that if German bindings attracted any attention in the course of the nineteenth century, soon after 1840, it was solely due to the binders. Purgold and Trantz, men of German origin, living in Paris, and to Kalthoefer and Zaehnsdorff, who were established in London. As a matter of fact, try as one will, it is impossible to deny that Germany, during the centuries in question, was very poor as regards art binders, and this fact makes its recent efforts to achieve celebrity in this direction all the more meritorious. Mr. Paul Kersten had few predecessors, and when he talks of Trantz and Kalthoefer he must mistake the facts connected with these artists. They did no work “at home ” – that is in Germany – but were “outsiders,” who cannot be taken into account on the present occasion. Mr. Kersten himself is one of the foremost German exponents of his art, and he may without vanity be proud of the eminent position he holds.

I have not had the opportunity of handling any of the volumes clothed by Mr. Paul Kersten, but have simply seen them in show-cases or in photographs, and on that account am somewhat ill-qualified to discuss them from the point of view of workmanship. Careful bibliophiles will be able to appreciate all the various points which constitute fine binding, but that which demands our attention here is rather the work of the decorator and the gilder, and here we find remarkable achievement – ornamentation at once sober and varied, admirable in taste and style.

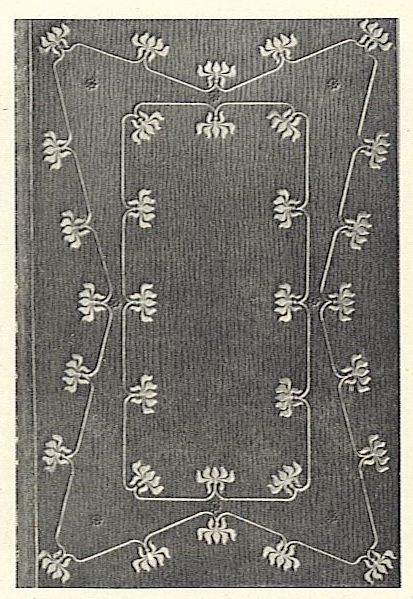

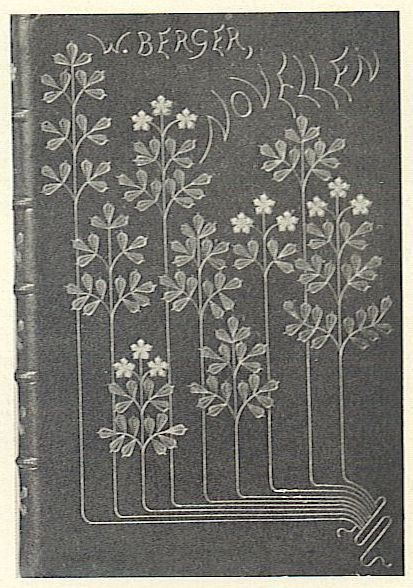

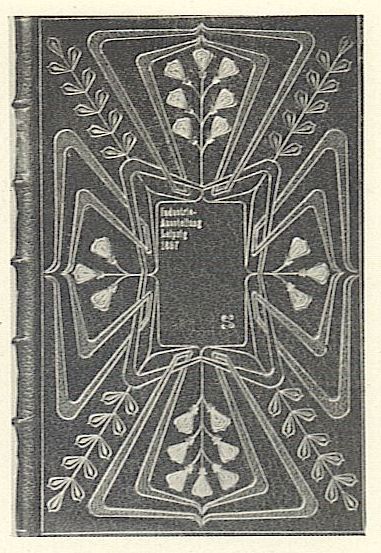

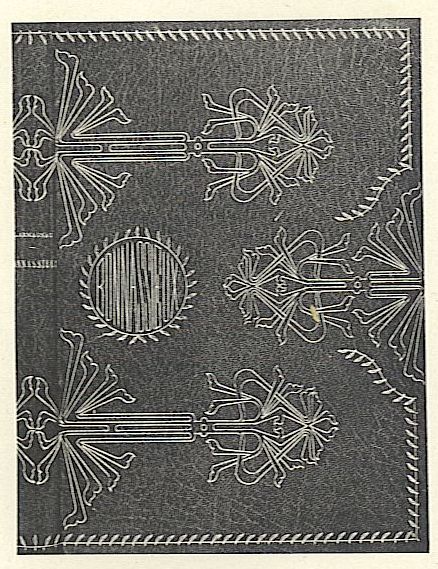

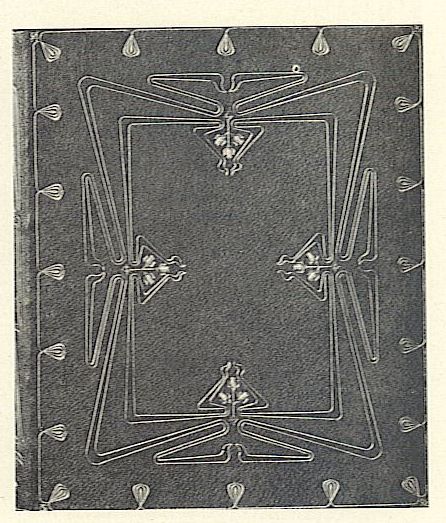

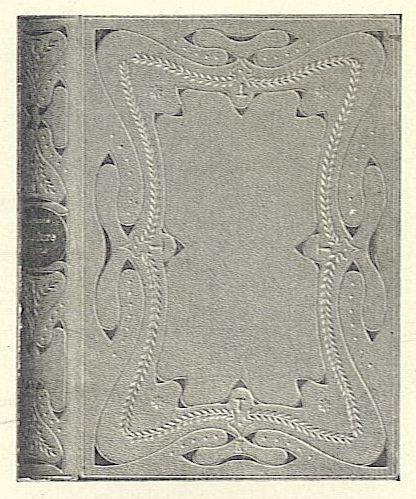

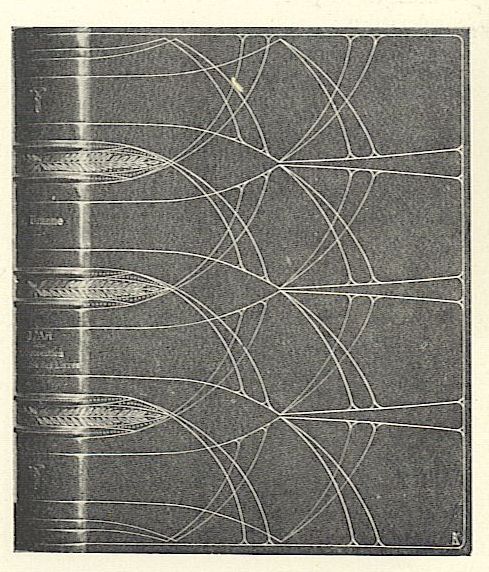

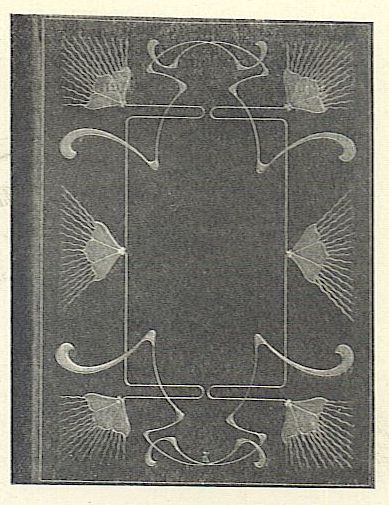

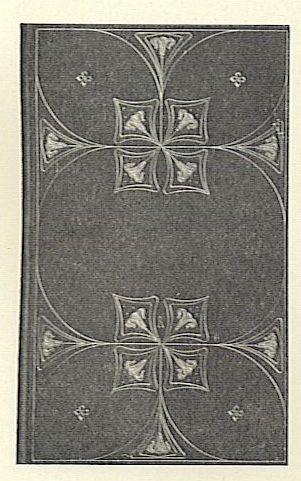

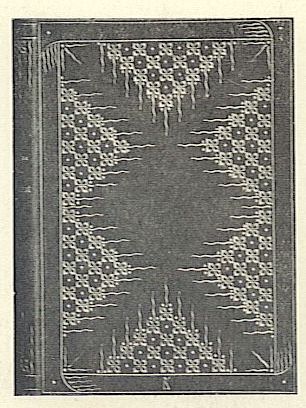

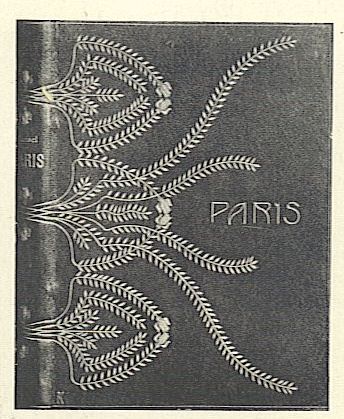

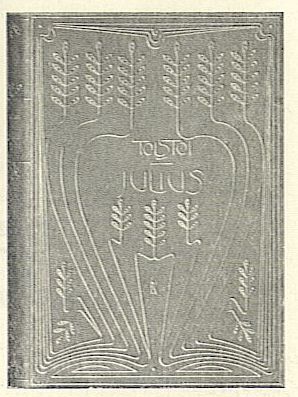

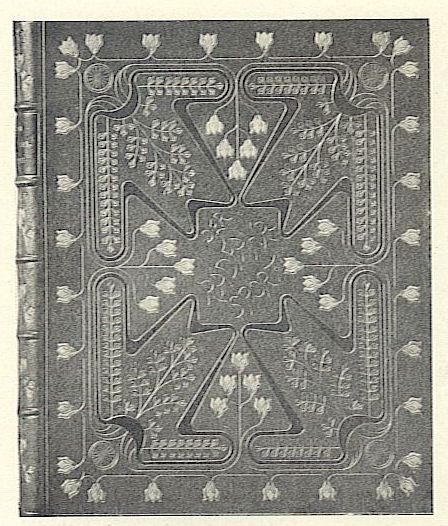

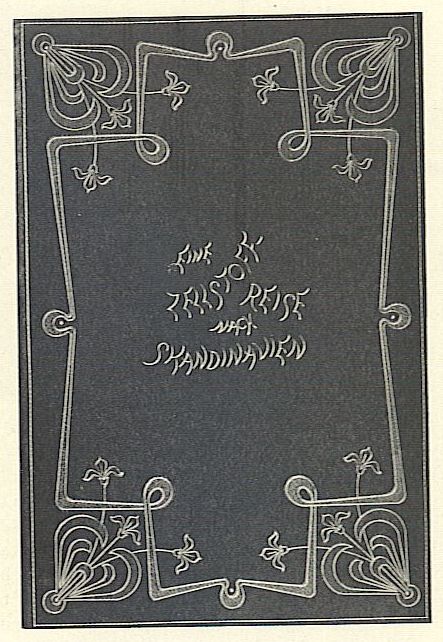

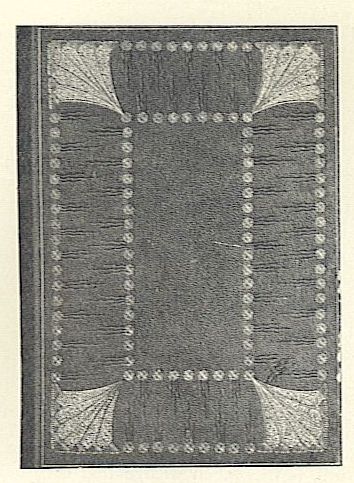

I have before me now in reproduction a large number of bindings executed from the unpublished designs of Mr. Paul Kersten, and not one can I find in which there is anything defective in the composition or which lacks harmony of ensemble. In each case the skilful gilder has sought to complete a decorative theme with great simplicity and breadth of touch, and everywhere he has succeeded in creating a striking field of decoration, without having recourse to loud effects or exaggeration of any sort. Look at some of the reproductions accompanying this text – at the “Julius” of Count Tolstoi for example, with its delicate, curved, parallel lines, forming a heart-shaped figure, leaving space for the title in graceful palm-leaves ; or at “L’Art dans la Decoration exterieure des Livres” , in which the sides and the back of the book are, as it were, involved in a wide, spider-like web of beautiful threads: or, again, at the “Paris” so minutely adorned with airy branches executed au petit fer. There is no apparent effort, no conscious elaboration about all this, yet how striking, how delightful it is to the eye! One feels that M. Kersten has only achieved these effects by a process of elimination, beginning with complication and ending with the most vigorous simplicity. This is sane, restful, temperate decoration, the lines showing up to perfection against the rich tone of the ground colour.

It is to be hoped M. Paul Kersten will make up his mind to exhibit the greater part of his bindings soon in London as well as in Paris : he has been hitherto, perhaps, rather too much absorbed by his native country ; and every true artist nowadays should have his success consecrated by Paris and London. In America, too, he would be no less appreciated, on account of the brightness, the variety, and the logic of his designs. He is the kind of man to stand universal renown and our modern binders should strive to deserve it by reclothing in new and magnificent garb the fancies of the great writers of all lands – Hugo, Swinburne, Tennyson, Goethe, and Macaulay, Balzac and Dickens, George Sand and George Eliot, Ibsen and Alexandre Dumas.

The age demands that merit shall no longer be confined at home. Progress requires stimulus, and no records are broken by remaining in the stagnation of self-content, whether it be private or national. The ” bibliodrome ” – if I may venture to coin the word – wherein decorative artists compete – tends to become more and more international, and it is necessary to know one’s rivals over the border, and to strive against them in all the marts of civilisation.

OCTAVE UZANNE.