BIBLIOPEGY IN THE UNITED STATES

AND KINDRED SUBJECTS

BY WILLIAM LORING ANDREWS

“To be strong-backed and neat

bound is the Desideratum of a volume.

Magnificence comes after.”

Essays of Elia.

Publisher’s note:

The following preface pertains to the prints published with the 1902 edition of Bibliopegy in the United States.

The printing details are of course irrelevant for the digital images from this web site.

The color illustrations from the book were scanned and published without alterations, the black and white were colorized to accentuate the details and give an idea of what the book may have looked like to the author.

PREFACE

THE color prints in this book have been produced by two diametrically opposite processes. Those of ” The Contrast,” “The Gift” and “The Rainbow ” are printed from relief plates treated in a special manner, two plates being required for the printing of each color of leather, one for the gold impression. These plates can be printed satisfactorily only upon a dry, highly finished paper.

Half-tone reproductions of leather bindings are by no means a novelty, but so far as I am aware, these plates are the first fairly successful reproductions of leather bindings, made directly from the books themselves by what is known as the direct process. Heretofore the tooled design has been redrawn on a large scale, and reduced to the proper size by photo-engraving ; an imitation of the grain of leather being produced by impressions from one or more additional plates.

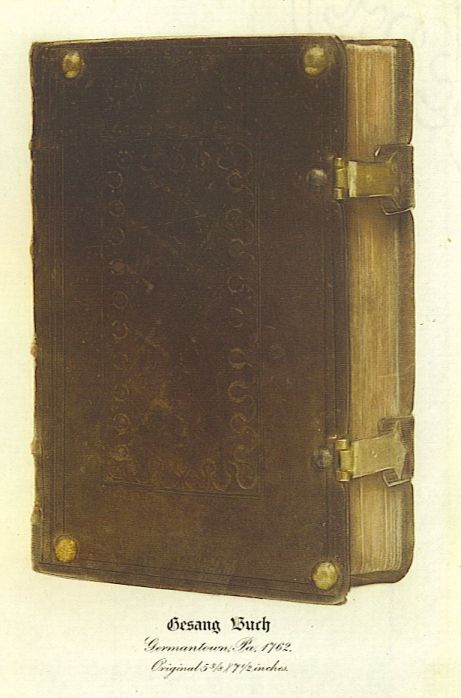

The pictures of the ” Gesang Buch,” the ” American Latin Grammar ” and the ” Prompter Book,” are printed from a single photogravure copper plate, on a wet paper, which may be either rough or smooth-surfaced. The Xll Preface colors in this process are applied to the plate by hand, and it is necessary, after each impression is taken, to clean and polish the plate – upon which the printer must then repeat the tedious operation of reapplying the colors. He virtually paints the copper-plate anew after each impression. This process was, I believe, first successfully employed in France.

It is needless for me to draw attention to the designs and engravings by Mr. Sidney L. Smith which happily this book contains. Every lover and collector of beautiful books will recognize in them a revival of the art of the French vignettists of the eighteenth century, in which was reached the acme of gracefulness and skill, in the decoration of the pages of a book.

W. L. A.

HAT book-binding is an ancient, honorable, and esthetic employment, will not be gainsaid by any intelligent student of industrial art, and yet it is only within the last quarter of a century, that it has begun to receive the attention to which it is deemed entitled by that small, but constantly recruited band of enthusiasts, who delight in fine books fitly bound, and who for this and other idiosyncrasies in regard to books, have been mercilessly satirized ever since the days of that ironical old scribe Sebastian Brant. Prior to this comparatively recent period, writers, both here and abroad, taking their cue, it may be, from the crusty author of ” The Ship of Fooles ” and his equally caustic translator, aiderr and abettor, Alexander Barclay, Priest, appear to have regarded the topic as a trivial one, and of too little general interest to justify the expenditure upon it, of even a modicum of their energies and talents ; but of late the times have vastly changed in this respect, and the art which is to so great an extent preservative of the Art of Printing – for without a binding the leaves of a book would speedily part company – has now a surfeit of notoriety. Those past masters in Bibliopegy – the Eves, Le Gascon, Padeloup Le Jeune and the various members of the numerous and talented family of Deromes, would, I fancy, start in amazement from their long, dreamless sleep, could they hear the paeans now chanted in praise of the handicraft they carried to such perfection, in their quiet eyries aloft amid the cooing and circling doves, under the eaves of the steep-pitched roofs, of the old city of Paris.

HAT book-binding is an ancient, honorable, and esthetic employment, will not be gainsaid by any intelligent student of industrial art, and yet it is only within the last quarter of a century, that it has begun to receive the attention to which it is deemed entitled by that small, but constantly recruited band of enthusiasts, who delight in fine books fitly bound, and who for this and other idiosyncrasies in regard to books, have been mercilessly satirized ever since the days of that ironical old scribe Sebastian Brant. Prior to this comparatively recent period, writers, both here and abroad, taking their cue, it may be, from the crusty author of ” The Ship of Fooles ” and his equally caustic translator, aiderr and abettor, Alexander Barclay, Priest, appear to have regarded the topic as a trivial one, and of too little general interest to justify the expenditure upon it, of even a modicum of their energies and talents ; but of late the times have vastly changed in this respect, and the art which is to so great an extent preservative of the Art of Printing – for without a binding the leaves of a book would speedily part company – has now a surfeit of notoriety. Those past masters in Bibliopegy – the Eves, Le Gascon, Padeloup Le Jeune and the various members of the numerous and talented family of Deromes, would, I fancy, start in amazement from their long, dreamless sleep, could they hear the paeans now chanted in praise of the handicraft they carried to such perfection, in their quiet eyries aloft amid the cooing and circling doves, under the eaves of the steep-pitched roofs, of the old city of Paris.

Few authors, little or great, since the days of that archetype of bibliophiles of loved and revered memory, Richard de Bury, have shown themselves possessed of a love of well-made books, or manifested any concern in regard to the manner in which their lucubrations were printed, bound, and presented to the public gaze. Apparently they regarded the matter with indifference, if not with a feeling akin to contempt – an altogether unnecessary painting of the fair lily of literature, which had budded and blossomed under their fostering care. This attitude on their part must strike even the casual observer, as being a rather short-sighted one, to say the least. Most writers, I have been led by observation to conclude, are not free from a touch of egotism and believe sincerely that ” the thoughts that breathe and words that burn” which flow from the tips of their fluent pens, deserve, and will achieve lasting fame. But how, pray, can they be transmitted to posterity, if printed upon paper that has latent within it the seeds of decay, and encased in machine-made bindings too unsubstantial, to withstand the gentlest usage for any protracted length of time, much less the rough-and-ready treatment that is quite certain to be their future lot; for few people know, or are solicitous to know, how to care properly for books and bestow upon them the zealous guardianship they require, in order to ensure them a ripe and serene old age. If the books of the ancients had been of as perishable a nature, as are the majority of those the modern press puts forth, the perennial fountains, from which we now draw the wisdom and learning of past ages, would have ceased to flow at their very sources, and we should have in lieu thereof, only the scanty and turbid rills of oral tradition and legendary lore. It is only too true that, never since printing was invented has there been a time, when books, as a rule, were in all respects, and not alone in the matter of binding, to so great an extent as they are to-day, the “larcenies from future ages” that Lesne, the poet bookbinder of the eighteenth century, declared poorly bound books to be.

For this state of things, the typographers are responsible. A decline in the art of printing, is inevitably followed by a decadence in the arts related thereto. A fine exterior presupposes a well made book; for as has been well said: ” The binding is the robe of honour in which we insert a noble book, and upon the binding, we impress its external insignia of rank and merit.” The conclusion which forces itself upon the mind of every one interested in the matter is this: that bookmaking in most of its branches, as practised with varying degrees of skill and taste for three centuries after the great invention of movable type, is to-day as completely a lost art as is that of Oiron pottery or the enamel of Limoges.

” Then a book was still a book,

Where a wistful man might look,

Finding something througth the whole

Beating – like a human soul

In that growth of day by day

When to labor was to pray,

Surely something passed

To the patient page at last.

Something that one perseves,

Vaguely present in the leaves,

Something from the workers lent,

Something mute – but eloquent.”

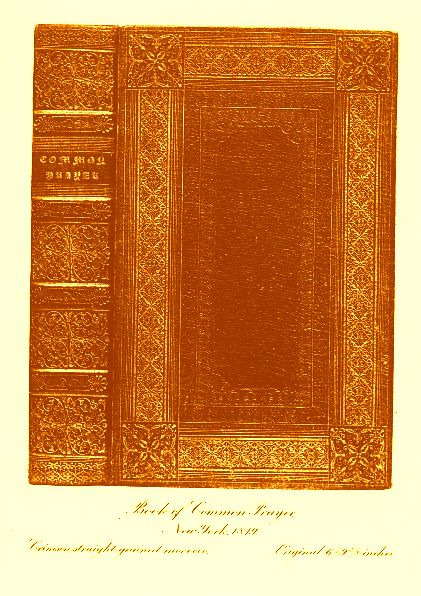

Truth and poetry are equally blended in these graceful lines of Austin Dobson, and now let us read the words penned by that scholar and bibliophile Richard GrantWhite, a quarter of a century ago, concerning the state of the arts of printing and book-binding in this great, free and enlightened Republic. “When I say that the art of printing and of book-making in general has not advanced in New-York, or even in the United States, within the last fifty years, I may expect a chorus of protest, in which I fear the voice of Henry Houghton, of the Riverside Press, may be heard. But I do say distinctly, and without reserve or qualification, that New-York could and did produce a handsomer book fifty years ago than she does (whatever her ability) now, and I hold myself ready to prove this by an example before a jury of experts in the art of book-making. This example is a copy of the Book of Common Prayer, published in New-York in the year 1819. The printing of it, both for accuracy and beauty, is admirable, and would compare advantageously with the best work of its period in England. The letter, the justification, the register, the ink, and the press-work are of the best kind, and have a solidity and dignity of expression which command respect. The binding, which is in straight-grained crimson morocco, is such as William Matthews need not be ashamed of, and such, indeed, as he himself puts only on the finest, specially ordered ‘ extra’ work. The taste of the ornament would not have satisfied Count Grolier, but it is far better than that of the usual English work of its period, and the delicacy of the tooling, both the gilt and the dead work, and the exactness of the mitring are quite equal to that of the most celebrated English binders of the time, superior, indeed, to Roger Payne’s. It might not unreasonably be supposed that such a book as this was printed and bound in England. Not so. It was stereotyped by ” D. & G. Bruce” New York, a well-known firm of that period, and it was printed by “J. & J. Harper” a New York printing firm tolerably well known at the present time, but then only of nascent fame. . . . Who was the binder I do not know, and I am sorry that I cannot give him credit for such a specimen of New York skill and taste at that period. It might be supposed that this copy was specially bound to order, which, however, if it were the case, would not affect the question of the skill and the taste of the period; but it is not so. This copy is not only one of two exactly alike which were in my father’s pew in St. George’s Church in Beekman Street, but I have seen other copies of it exactly like these in design and execution, although the work is not done with a stamp, but what is known as hand-tooling. This shows that the book was bound up for general sale in this style, and although it, of course, must have been very costly at that time, particularly as it is illustrated with line engravings, none the less it is like St. Paul’s Church, the Old City Hall and the statue of Hamilton, a witness to the taste and culture of New York, and the skill of her artisans fifty years and more ago.”

This is warm praise and sharp criticism, and will no doubt be met with a smile of incredulity by our modern book-makers, but the bibliophile will endorse every word of it, save, I trust, the statement that the binding on this Book of Common Prayer is superior to any produced by Roger Payne. I would not name them in quite the same breath, for one is the work of a master, whose style of decoration, as William Matthews has truthfully said, was strikingly his own, the other that of a pupil and imitator. Furthermore the paper used in the book so highly extolled by Mr. White must have contained that deleterious ingredient, which proved the bane of so much of the paper manufactured at that period, both here and in England, and caused it in process of time to ” fox ” and turn a dirty brown in spots, but Mr. White probably was not aware of this imperfection when he wrote his spicy comment and threw down his gauntlet to the book-makers of New York.

We are more fortunate than the Shakesperian commentator in that we have before us two copies of this Book of Common Prayer bound in the style that he describes, one of which, an heirloom in the family of Mr. Beverly Chew, contains the binder’s ticket, H. I. Megary, a New York stationer, printer and publisher in the early part of the last century whose name is well and favorably known to collectors of engraved pictures of the City of New York. The other copy, belonging to Mr. Bowen W. Pierson, is in the same style, and the same tools were employed in the decoration, but were worked after a different design. The lettering on the back is in Gothic type, a character we would not be surprised to find employed upon the back of a black-letter ” fifteener,” but its use on a modern book is quite exceptional.

The artistic binding and exterior decoration of books, so long a neglected study, may be said without exaggeration to have latterly become a rage. Annual exhibitions of richly-decorated bindings, are conspicuous features of our Metropolitan bookshops, and treatises more or less erudite upon the Art of Book-binding, follow one another in rapid succession from a press whose watchful pilots are ever closely scanning the literary horizon, and stand prepared to trim their sails hourly, if need be, in order to catch the shifting winds of capricious popular fancy. Thus the pendulum swings to and fro, and we vibrate from one extreme to the other in our tastes and temporarily ruling passions. The Bibliography of books upon Bookbinding, published in 1893 by Miss S. T. Prideaux, herself a successful practical exponent of the Art, embraces four hundred and seventy-five titles. In the years that have since elapsed additional works by the score have made their appearance, many of which are little more than compilations from the writings of previous authors. A small proportion, such as essays by those whose own trained and skillful hands have produced fine examples of book-binding, have made us, no doubt, more conversant with the technical methods and the mysteries of the craft, but from an historical point of view the subject was exhausted long ago. We have been told with tiresome repetition of the books “so fairly bound ” which graced the famous libraries of those munificent patrons of the arts, Maoli, Grolier, Canevari, De Thou and those ” light and airy ladies ” of fastidious taste in books and bindings, Margaret of Valois and Diana of Poictiers; of the books elaborately tooled and richly painted for the kings, queens, princes, prelates and statesmen of Italy, France and England, which long since were allotted their rightful place among the priceless art treasures of the world; of the Eves, Gascons, Padeloups, Monniers, Deromes, Capes, Trautz-Bauzonnets, Chambolle-Durus and Cuzins: the Mearnes, Roger Paynes, Lewises and Bedfords: the French tinselled and silk – embroidered bindings, and those deftly fashioned and patiently wrought by the pious hands of the nuns of Little Gidding, but few and faint are the whisperings that fall upon our listening ears, concerning Bibliopegy on this side of the broad and boisterous Atlantic.

In the report of a French delegation of artisans to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition* sixteen pages are allotted to a description of the American bindings there displayed, which were, however, largely composed of the commercial bindings of the time and the heavily stamped and floridly gilded outward covers of the Pictorial Histories, and huge illustrated Family

* ” Exposition Universelle de Philadelphie, 1876. DELEGATION OUVRIERE Libre RELIEURS.” Paris, 1879.

Bibles, which were the pride of our forbears and lent an air of distinction to the parlor centre table, in all well-to-do and well-regulated households. Mr. Brander Matthews in his ” Book-Bindings Old and New” descants at some length upon Modern bookbinding in the United States, and we find here and there in other publications * curt paragraphs of a disparaging tenor similar to the following, which we quote from Octave Uzanne’s “La Reliure Moderne” but in respect to the practice of the Art in this country prior to the days of William Matthews the silence is, we repeat, well nigh profound. ” L’Amerique [writes M. Uzanne] se rejouit de posseder Matthews, que les New-Yorkais considerent comme un demi-Dieu et qu’ils inondent de centaines de dollars,

* ” L’ Art dans la Decoration Exterieure des Livres en France et a l’Etranger,” Paris, 1898, devotes a page and a half in a book of 275 pages to American bindings and mentions the names of Matthews, Bradstreet, The Club Bindery, Smith and Stickerman (Stikeman).

lorsque celui-ci daigne, des ses propres mains, revetir une belle edition de brown or red maroco. Matthews a cree une genre d’ornamentation; c’est un original, et ses reliures peuvent hardiment se comparer a celles de MM. Marius-Michel, sauf peut-etre ce (je ne sais quoi) qui tient la grace francaise et qui ne saurait passer les mers sans y perdre son caractere.” Have a care, Monsieur Uzanne. Evidently some one has been imposing upon your credulity, for I can and do here testify of my own knowledge that Mr. Matthews’s charges for his finest bindings were moderate in the extreme. They were done, be it understood, for friendship’s sake and not for gain, and Mr. Matthews would not, I am quite certain, have undertaken the elaborate binding of a book for any and every one, no matter how many ” centaines de dollars ” might be cast at his feet. The Frank in matters of Art is sufficient unto himself. As for book-binders, he believes in his heart of hearts that there never were nor will be any outside of his own beautiful and adored city of Paris, worthy of the name. That the Parisian book-binders stand, and always have stood, in the front rank of their profession, no bibliophile the world over will deny. But is not variety the spice of life? The gastronome, if restricted to a single article of diet for a length of time, finds that it palls upon his palate, even though the dish be concocted with all the culinary skill of a Careme or a Vatel. We of the Anglo-Saxon race – more catholic, if less refined, in our tastes than the perhaps hyper-esthetic descendants of the ancient Gauls, enjoy the lesser art achievements of other nations, in which the French dilettante manifests little or no concern, simply because they are not the products of the skill and genius of his own countrymen.

Apologetical of this indifference and neglect on the part of our own, as well as European writers upon Bibliopegy, the undeniable fact may be adduced that our book-binders had not, until the last thirty or forty years (except for a brief period immediately after the close of the Revolutionary War which ended as unaccountably and precipitately as it began), shown themselves able to produce work that could be pronounced artistic. A survey of the Art as it flourished in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries leads us through the winding paths of a well-ordered garden bright with the variegated colors, and redolent with the fragrance of lovingly and patiently nurtured flowers; whereas a study of Bibliopegy, as it was haltingly and laboriously developed in this country during the corresponding period, conducts us for most of the tiresome way over a field of brown and withered winter stubble. For many years the Bindery in the United States remained a subsidiary but necessary adjunct to the Printing House, and nothing more. It required a generation of book-lovers and collectors, and the imperative demand thereby created, to establish Artistic Bibliopegy in our midst as a separate and distinct occupation. But books have been bound by our native workmen after one fashion or another, and better, on the whole, than might have been expected, for the past two centuries and a half, and the story of the craft from its humble beginnings in New England, in the seventeenth century, to modern times, should not be devoid of interest to the American bibliophile, if to no other, and he assuredly is the one to be reckoned with in the immediate future of book-collecting, for he happens, just now, to be the possessor of the best lined purse, and by virtue thereof, master of the situation.

In a work by one Edward Hazen, entitled ” The Panorama of Professions and Trades, or Every Man’s Book” published in Philadelphia in 1837, a definition is given of the word book-binding which is a model of conciseness, and would not discredit the pages of a Webster, a Worcester, or a Century Dictionary. Book-binding is defined by Mr. Hazen as the ” Art of arranging the pages of a book in proper order, and confining them there by means of thread, glue, paste, pasteboard and leather.” Here we have, in a nutshell, the essential significance of this compound word.

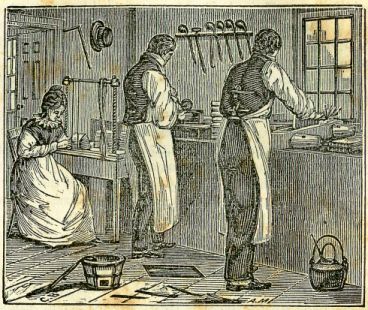

This little book by Hazen is quite in the spirit and manner of one published at Frankfort-On-Main in 1568, in which the various professions and trades (paper-making, printing, and book-binding amongst them) followed in Germany, in the sixteenth century, are described in metrical Latin and represented pictorially with engravings by Hartman Schopfer. It is not probable that Hazen was acquainted with this work of Schopfer, and guilty of an act of plagiarism, and we may, therefore, regard this coincidence simply as a proof that in the kingdom of letters, lapse of years and accident of locality, play little part.

The description of the various processes involved in the binding of a book contained in Mr. Hazen’s “Every Mans Book” which with its woodcut head-band we here present to the reader, is, so far as I am aware, the first treatise upon the subject printed in the United States, and considering the backward state of the Art in America at the time it was written, it is noteworthy for the general knowledge of the subject it evinces.

The first process of binding books consists in folding the sheets according to the paging. This is done by the aid of an ivory knife, called a folder, and the operator is guided in the correct performance of the work by certain letters called signatures, placed at the bottom of the page, at regular intervals through the book.

Piles of the folded sheets are then placed on a long table in the order of their signatures, and gathered one from each pile, for every book. They are next beaten on a stone, or passed between steel rollers to render them smooth and solid. The latter method has been introduced within a few years. This operation certainly increases the intrinsic value of the book ; but it is not employed in every case, since it is attended with some additional expense, and since it diminishes the thickness of the book, and consequently its value in the estimation of the public at large.

The sheets, having been properly pressed, are next sewed together upon little cords, which in this application, are called bands. During the operation these are stretched in a perpendicular direction at suitable distances from each other, as exhibited in the foregoing cut. The folded sheets are usually notched on the back by means of a saw, and at these points they are brought in juxta-position with the bands. After the pages of several volumes have been accumulated, the bands are severed between each book. The folding, gathering, and sewing are usually performed by females.

At this stage of the process, the books are received by the men or boys, who generally take on one hundred at a time. The workman first spreads some glue on the back of each book with a brush. He then places them, one after the other, between boards of solid wood, and beats them on the back with a hammer. By this means the back is rounded, and a groove formed on each side for the admission of one edge of the pasteboards.

These having been applied, and partially fastened by means of the bands, which had been left long for the purpose, the books are pressed and the leaves of which they are composed are trimmed with an instrument called a plough. The pasteboards are also cut to the proper size by the same means, or with a huge pair of shears. In the preceding picture a workman is represented at work with the plough. The edges are next sprinkled with some kind of coloring matter, or covered with gold leaf, A strip of paper is then glued on the back, and a headband put upon each end.

The book is now ready to be covered. This is either done with calf, sheep, or goat skin, or some kind of paper or cloth; but whatever the material may be, it is cut into pieces to suit the size of the book, and having been smeared on one side with paste, it is drawn over the outsides of the paste-boards, and doubled in upon the inside.

The covers, if calf or sheep skin, are next sprinkled or marbled. The first operation is performed by dipping the brush in a kind of dye, made for the purpose, and beating it with one hand over a stick held in the other; the second is performed in the same manner, with the difference that they are sprinkled first with water, and then with the coloring matter.

After a small piece of morocco has been pasted on the back, on which the title is to be printed in gold leaf, and one of the waste leaves has been pasted down on the inside of each of the covers, the books are pressed for the last time. They are then glazed by applying the white of an egg with a sponge.

The books are now ready for the reception of the ornaments, which consist chief- ly of letters and other figures in gold leaf. In executing this part of the process, the workman cuts the gold into suitable strips or squares on a cushion.

These are laid upon the books by means of a piece of raw cotton, and afterwards impressed with types moderately heated over a charcoal fire; or the strips of gold are taken up and laid upon the proper place with instruments called stamps and rolls, which have on them figures in relief. The portion of the leaf, not impressed with the figures on the tools, is easily removed with a silk rag. The books are finished by applying to the covers the white of an egg and rubbing them with a heated steel polisher.

The process of binding books, as just described, is varied, of course, in some particulars to suit the different kinds of binding and finish. A book, stitched together like a common almanac, is called a pamphlet. Those which are covered on 30 And Kindred Subjects the back and sides with leather are said to be full bound, and those which have their backs covered with leather, and the sides with paper, half bound.

The different sizes of books are expressed by terms, indicative of the number of pages printed on one side of a sheet of paper; thus, when two pages are printed on one side, the book is termed a folio; four pages, a quarto ; eight pages, an octavo; twelve pages, a duodecimo; eighteen pages, an octodecimo. All of these terms, except the first, are abridged by prefixing a figure or figures to the last syllable. Thus, 4to for quarto, 8vo for octavo, I2mo for duodecimo, etc.

In the quiet sanctuary of the soon-to-be-evicted Lenox Library, where repose in peace for yet a little season so many rare and priceless manuscripts and printed books drawn thither by its founder from the Scriptoriums and Presses of both the old and new worlds,

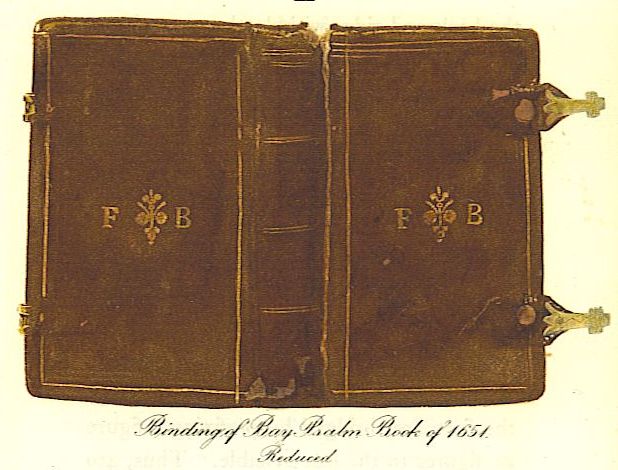

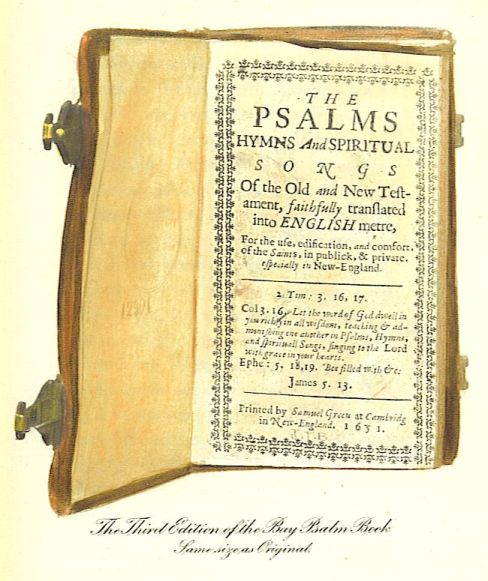

there is a copy of ” The Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual Songs” printed in 1651 by Samuel Green, the successor of Stephen Daye, New England’s first typographer. This little volume – only 2 1/2×4 1/4 inches in size – of about 400 pages, is known as the THIRD edition of the Bay Psalm Book. It is of greater rarity (for this, I understand, is the only copy of it known) than its predecessor and namesake which enjoys the distinction of being the first book printed in British North America, but it is hardly necessary to add that it does not approach it in money value.

It came from Mr. Charles H. Kalbfleisch’s remarkable collection, whom it is said to have cost one thousand dollars, and was presented to the Library by Mr. Alexander Maitland. It is well and stoutly bound in brown calf, the covers held together by leathern and brass clasps, the only attempt at ornamentation being a narrow gold line traced around the borders of each side, a small centre ornament, and the initials F. B. If it is, as we presume, the original binding, it is one of the earliest examples extant of bookbinding executed in the Province of Massachusetts, and consequently in this part of North America, for the old Bay State may pride itself upon having been the cradle of Bibliopegy, as well as of Typography, in the new and unsettled land of our forefathers. This edition of the Psalms turned into Metre is known as the “Bay Psalm Book Improved.” The nature of the revision which the first issue of this noted book underwent, will be seen by the parallels we have drawn below of the first, second and sixth stanzas, of the First Psalm, in the two editions.

The Bay Psalm Book

1640

1

O Blessed man, That in th’ advice

of wicked doeth not walk;

nor stand in sinners way, nor sit

in chayre of scornfull folk.

2

But in the law of Jehovah,

is his longing delight:

and in his law doth meditate

by day and eke by night.

6

For of the righteous men the Lord

acknowledgeth the way:

but the way of ungodly men,

shall utterly decay.

The Bay Psalm Book Improvised

1651

1

O blessed man yt walks not in

th’ advice of wich men

Nor standeth in ye sinners way

nor scorners sits in.

2

But be upon Jehovah’s law

doth get its whole delight;

And in his law doth meditate

both in the day and night.

6

For of the righteous men the LORD

acknowlegeth the way

Whereas the way of wicked men

shall utterly decay.

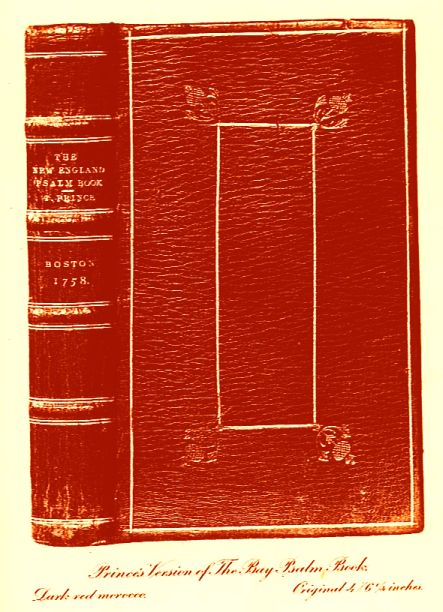

The Bay Psalm Book passed through many editions without further alterations, until it was revised in 1758, by the devout and learned theologian, Rev. Thomas Prince.

The copy of this edition in the Lenox Library is probably in its original morocco binding, for the same tooling precisely appears upon a more ordinary copy of the book, bound in dark brown calf of which the same library is the owner. Special care was doubtless taken with this particular book, as it was a presentation copy from the reverend author to ” The Honourable Thomas Huchinson Esq., Lieut. Govr.y &c., of The Province of the Massachusetts Bay in NE” but whether it was bound in England or this country is a question the writer admits his inability to answer. A full account of the Bay Psalm Book and of the numerous American, English and Scotch editions through which it passed, will be found in ” A History of Music in New England” by George Hood, Boston, 1846. The last edition of this noted Psalmody issued in this country, was in the year 1762.

Our first typographers were, as has been already stated, of necessity their own bookbinders. The columns of our early colonial newspapers contain, almost without exception, advertisements announcing the preparedness of the printers and publishers thereof, to undertake the binding of books. These paragraphs recur as constantly as do the now seemingly shameful proclamations of rewards offered for the return of runaway slaves, and notices of slaves for sale, which, with news from Europe three to six months old, make up the contents of these little weazen-faced, sallow-complected four-page journals. In Mr. William Bradford’s Gazette the following advertisement appears, with the regularity of clock-work :

” Printed and sold by William Bradford in New York where advertisements are taken in and where you may have old books, new Bound, either Plain or Gilt, and Money for Linen Rags.” The copy in the Lenox Library of “The Mohawk Prayer Book”* translated by Lawrence Claesse, and printed by Bradford in 1715, is believed to be in its original binding. If this be so, it supplies, I take for granted, an example of the “plain ” bindings, which our proto-typographer announces, as above, his ability to execute. It is a binding of ” dull and ugly plainness ” in sprinkled sheep, the edges spattered with red, but mind ye! should you strip off that old time-stained leather jacket

* Mohawk Prayer-Book. ” The Morning and Evening Prayer, the Litany, Church Catechism, Family Prayers, and Several Chapters of the Old and New-Testament, translated into the Mahaque Indian Language, by Lawrence Claesse, Interpreter to William Andrews, Missionary to the Indians, from the Honourable and Reverend the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. ” Ask of me and I will give thee the Heathen for thine Inheritance and the Utmost Parts of the Earth for thy Possession, Psalm 2.8.” Printed by William Bradford in New York, 1715.

and replace it with one in crushed levant, triple-gilt by Chambolle, Lortic, or some other Maitre moderne de Bibliopegie du premier rangy you would simply rob it of at least one-half its value, in the eyes of every Book-Antiquary of judgment and experience.

Similar notices to the one in William Bradford’s Gazette appear in the ” Philadelphia American Weekly Mercury” published by Andrew Bradford, and in the ” Pennsylvania Gazette, Printed by Benjamin Franklin, Post Master at the New Printing Office near the Market [Philadelphia] , where advertisements are taken in and book-binding is done reasonably in the best manner.”

William Parks, printer and publisher of The Maryland Gazette” (1729),likewise puts himself forward as a binder of books in the following language: ” N. B.- Old Books are well bound by him”

and Henry De Foreest advertises in his ” New York Evening Post” January 17th, 1750, that “all sorts of blank books for Merchants’ Accompts are for sale by the printer thereof, Also Old Books Neatly Bound, Lettered or Gilt very expeditiously”. These extracts, taken at random from the dusty files of American journals of the Eighteenth century, will suffice to show how generally in those primitive times the printing and the binding, – such as it was, – of a book, were the allotted task of one individual or business firm. As an exception to prove this rule we note the advertisement in Bradford’s Gazette, September, 1734, of one Joseph Johnson, that “he is now set up Book-binding for himself as formerly, and lives in Dukes St. (commonly called Bayard St.) near the Old-Slip Market; (New York) where all Persons in Town or Country, may have their Books carefully and neatly new Bound either Plain or Gilt reasonable.”

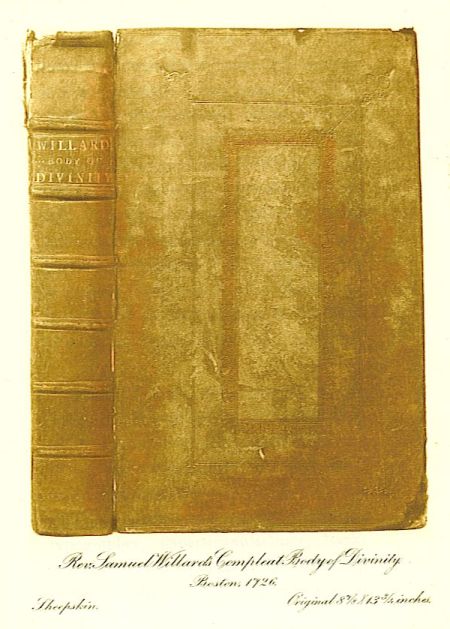

In Samuel Willard’s “Body of Divinity” Boston, 1726, one of the controversial writings of which the literature of Puritan New England so largely consisted, we have an example of American book-making from start: to finish.* It is a large folio – one of the first books of its size printed in New England – bound in foxy brown sheep-skin with panelled sides, and so far as the makers were able to accomplish that result, it is a counterpart of contemporaneous English binding. We copied, as best we could, and I fear without proper acknowledgment, both the exteriors and the interiors of the popular English books of the day. As one out of many instances of this practice that might be supplied, we reproduce on a reduced scale one of the plates in a London (1794) edition, of a little work, on the Newtonian system of Philosophy, and one from a reprint of it published in Philadelphia in 1803.

*A Compleat Body of Divinity etc., by the Reverend and Learned Samuel Willard, M.A., Boston, in New England.

Printed by B. Green and S. Kneeland for B. Eliot and D. Henchman and sold at their shops. MDCCXXVI

The latter is illustrated with exact reproductions of the engravings in the London edition, except that the plates are reversed and enlarged as shown on pages 48 and 49. These copies were engraved by William Rollinson, an artist who enjoyed the unique distinction of having chased the buttons upon the coat worn by Washington, at his first inauguration as President of the United States, in Federal Hall, New York. Rollinson’s descendants are still engaged in the business of copper-plate engraving in this city.

Isaiah Thomas, whose position as the foremost and most prolific (it is said that at one time he had sixteen presses in use and owned eight book-stores) of New England’s eighteenth-century printers, is now clearly recognized, was author, antiquarian, typographer, paper-manufacturer, bookbinder and book-seller all in one. Of which of the disciples of Gutenberg of the present day can all this be said ? That Thomas was also a born bibliophile will, I think, appear by what I shall presently relate.

The proclivity, amounting at times to a mania, of the ordinary bookbinder to plough ruthlessly through the leaves of a book, even though the process involves the snipping away of the entire margin and occasionally of a portion of the author’s text, is so well known to the fraternity of book-collectors as to have become proverbial. Listen to friend Thomas’s timely word of caution upon this vital point!

” The Directions to the Binder ” in the ” Elegiac Sonnets and other Poems by Charlotte Smith” published by Thomas at Worcester, Mass., in 1795, contain, in addition to careful instructions for the placing of the plates, this admonition to the binder: ” CUT THE BOOK As LARGE EACH WAY As IT WILL BEAR.”

These “directions ” of old Father Isaiah, with the addition of a short postscript to this effect, “AVOID WHENEVER POSSIBLE ANY USE OF THE KNIFE,” might well be engrossed in capital letters and hung upon the wall of every book-binder’s shop in the land. This articleic principle should be impressed with emphasis upon the mind of every apprentice to the art of book-binding, as one of the axioms of his craft.

Thomas states in his “advertisement” that the paper upon which the ” Elegiac Sonnets ” of Charlotte Smith is printed ” is a new business in America, and but lately introduced into Great Britain; it is the first manufactured by the editor”. He further informs us that the plates were executed, not by European engravers who settled in the United States, but by an artist who obtained his knowledge in this country. The book, therefore, is throughout of purely domestic manufacture.

This eminent Boston and Worcester printer, the Founder, President and Benefactor of the American Antiquarian Society (for which he erected a building at Worcester, Massachusetts), bound books in a variety of styles pursuant to the notice he inserted at the foot of the green paper covers in which the monthly parts of the Royal American Magazine, edited and published by him and Joseph Greenleaf, were issued, to wit: ” Book-binding performed in all its branches with great care and cheap.”

Thomas’s Chap-Books, such as ” The Devil and Dr. Faustus” were covered with a coarse and substantial brown canvas – a coat of buckram – than which, says Andrew Lang, there is nothing cheaper, neater or more durable. The numerous children’s books, ” Little Goody Two Shoes” ” The Juvenile Biographer” and the like, which, issued from the ” Columbian” as Thomas named his press, were clad in gay coats of gilt and brilliantly tinted papers, with intent to delight the eyes and conjure the pennies from the pockets of our grandparents, when they were yet in their knickerbockers and short frocks.

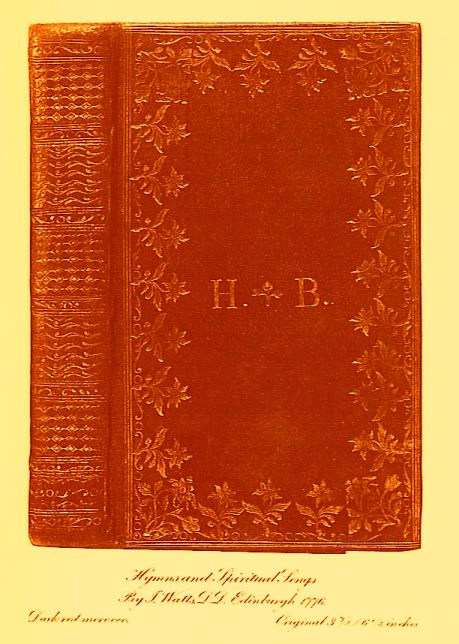

The plain leather bindings of Isaiah Thomas are, I judge, represented by the one shown in our plate, which covers a copy of ” The Psalms of David, Together with Hymns and Spiritual Songs, with Indexes, and Tables complete by Isaac Watts, D. D.,” Isaiah Thomas, Worcester, 1786. It is of sheepskin over oak boards, the former now decidedly the worse for wear. I have not been able to identify Thomas’s more elaborate bindings, if any such have survived to our time.

The German is nothing if not conservative, and his racial characteristics are slowly modified by new environments. Consequently we are prepared for the Teutonic plainness and solidity of the brass-knobbed calf binding, with its brass-tipped leather clasps, which covers, as with a coat of mail, the Gesang Buch, printed at Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1762, by Christopher Sauer, 2d, for the spiritual comfort of his Dunker Brethren, in their vernacular tongue, and the black-letter type of their Fatherland. The sides have a panel in dumb* or blind tooling which is a modest attempt at decoration, but the book now stands in need of none, for the rich mahogany color and glossy surface which the leather has acquired through careful, reverent use, and the alchemy of time, make full amends for all other deficiencies. This sombre-looking volume, from the hands of the pre-Revolutionary typographer, is indeed a very pleasant thing to sight and touch, and its strong and honest construction inspires one with a feeling of respect, for both the book and its maker.

*”This is an ornamental operation applied after the book has been polished. It is executed in the same way and with the same tools as for gilding, but without any gold applied on the places thus ornamented.”—Arnett’s Bibliopegia.

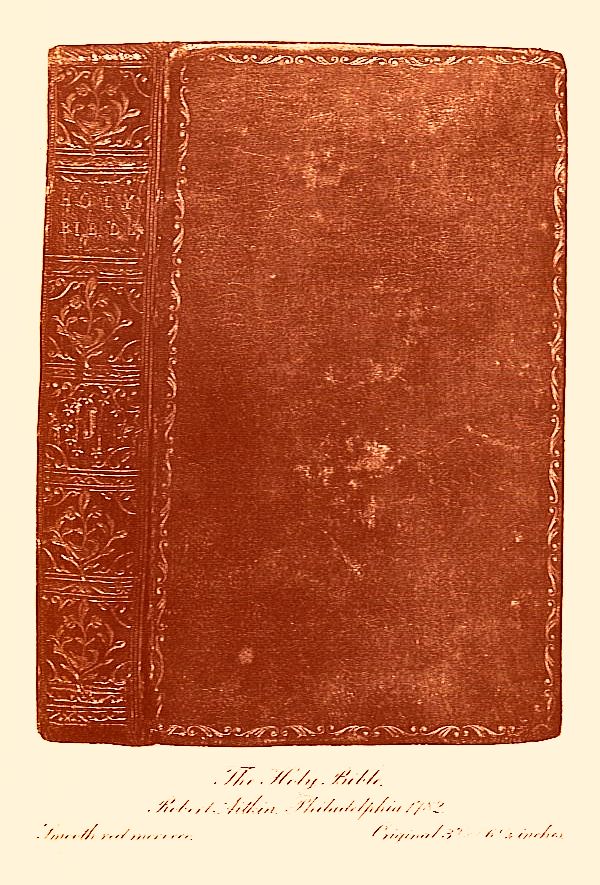

It has been said that the history of music in New England for the first two centuries is the history of Psalmody alone. It might be asserted with equal truth that the history of book-binding in this country in colonial days, brings us in contact with little besides books of a religious character. Bibles, Psalm and Prayer-books, and Theological Works almost monopolized the time and services of the Printer. As we turn from this book of sacred songs printed by Christopher Sauer, the next volume that falls under our notice is the Book of Books, namely, the English version of the Sacred Writings, printed by Robert Aitkin in 1782.

Robert Aitkin, best known perhaps as the publisher of the Pennsylvania Magazine, which began and ended its journalistic career during that critical period in our national life, the years 1775 and 1776, was born, we are told by Isaiah Thomas, at Dalkeith, Scotland, and served a regular apprenticeship with a book-binder in Edinburgh. He came to Philadelphia in 1769 as a book-seller; returned to Scotland the same year, but came back to this country in 1771, and followed the business of bookselling and book-binding both before and after the Revolutionary War. In 1774 he became a printer, and in 1781-2 printed, at a very considerable pecuniary loss, upon a poor quality of paper manufactured in the State of Pennsylvania, an edition in small octavo of The Holy Bible, which is claimed and generally conceded to be, the first version of the Scriptures in English published in this country; but in Isaiah Thomas’s account, in his ” History of Printing” of the Boston printers, Kneeland and Green, we find the following statement (Vol. I, p. 305):

“The book-sellers of this time were enterprising. Kneeland and Green printed, principally for Daniel Henchman, an edition of the Bible in small 4to. This was the first Bible printed in the English language in America. It was carried through the press as privately as possible, and had the London imprint of the copy from which it was reprinted, viz. : ” London, Printed by Mark Baskett, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,” in order to prevent a prosecution from those in England and Scotland, who published the Bible by a patent from the crown; or Cum privilegio, as did the English universities of Oxford and Cambridge. When I was an apprentice, I often heard those who had assisted at the case and press in printing this Bible, make mention of the fact. The late governor Hancock was related to Henchman, and knew the particulars of the transaction. He possessed a copy of this impression. As it has a London imprint, at this day it can be distinguished from an English edition, of the same date only by those who are acquainted with the niceties of typography. This Bible issued from the press about the time that the partnership of Kneeland and Green expired. The edition was not large; I have been informed that it did not exceed seven or eight hundred copies”.

This story is doubted by Bancroft and other historians, but Thomas was an author of more than ordinary accuracy and reliability, and some there are who, having investigated the matter, are inclined to the belief that an edition of the Bible was surreptitiously printed by Kneeland and Green as Thomas relates.

Two copies of the first volume of the Aitkin Bible are preserved in the Lenox Library. One is bound in smooth red, the other in olive morocco ; the back of the latter being tooled in a style faintly suggestive of the lace-like pattern characteristic of the bindings of the great French article, Padeloup Le Jeune. The back of the copy in red morocco, is decorated with a design similar in character, to that upon the sides of the copy of “Watts’ Hymns and Spiritual Songs” to which we shall shortly refer. These bindings are unsigned, but it may be presumed that they represent Aitkin’s skill in the dual capacity, of printer and book-binder.

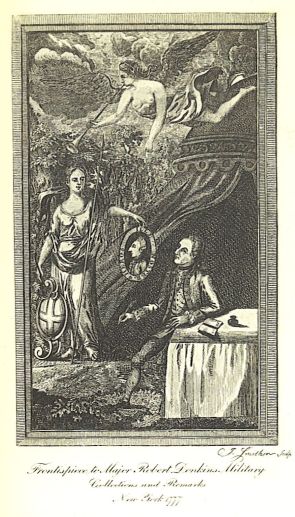

Another of the books in the Lenox Library, the binding upon which might, at a venture, be taken to illustrate a minor phase of our subject, is a copy of Major Donkin’s ” Military Collections” printed by Hugh Gaine, New York, 1777. It is an octavo bound in red skiver (split sheepskin) without the slightest attempt at ornamentation, but aside from the binding the book is interesting for its allegorical frontispiece said to represent Hugh, Earl Percy, being rewarded by Britannia, with Major Donkin seated at a table (Donkin was a Major in the British army serving in America in 1777), engraved by J. Smither, an artist whom Dunlap asserts occupied a unique position in the Arts of his time.

He was, writes the author of the ” History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States” originally a gun-engraver and employed in the Tower of London. He came to Philadelphia in 1773 and undertook all kinds of engraving. He probably stood high in public opinion ; he was the best, for he stood alone. We do not clearly comprehend this singular assertion, for certainly there were others, such as Doolittle, Hill, Turner and Trenchard among Smither’s cotemporaries, whose engravings appear to us to equal, if not to excel his work.

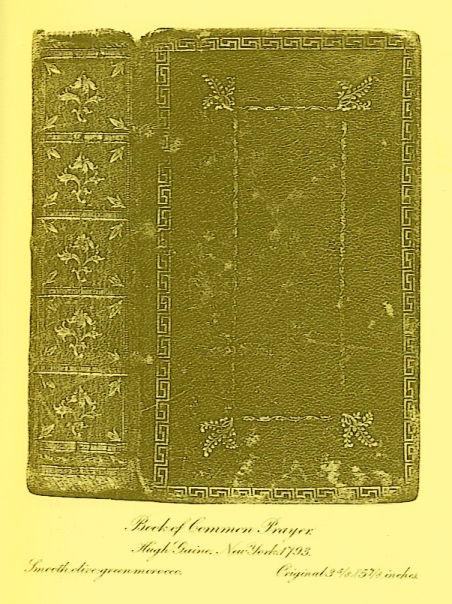

If this book of Major Donkin was bound by the printer of it, as may possibly be the case, we have here an example of Hugh Game’s plain morocco binding, and perchance we may also attribute to him the binding, in olive morocco gilt, on the “Book of Common Prayer” Hugh Gaine, Printer, at the Sign of the Bible, in Hanover Square, New York, 1793, in the possession of Mr. Beverly Chew. This edition, which was published by direction of the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, the same printer followed, two years later, by one in large folio, for use at the lectern of the Church. It is printed in bold, clear type, and handsomely bound in mottled and sprinkled calf. It is probably as fine a piece of typography as ever issued from the press of the ” turn-coat ” printer, who was deservedly made to say in a poetical version of his petition at the close of the Revolutionary War,

“And I always adhere to the sword that is longest

And stick to the party that’s like to be strongest.”

If Gaine’s political principles and rule of action, had been as sound as the printing of this folio Book of Common Prayer, he would have left a less unsavory memory.

A copy of this noble Episcopal Church Service book, presented by the Scotch merchant, Robert Lenox, ” to his most respected friend James Sheafe,” in 1812, may be seen in the Library founded and endowed by his Presbyterian book-loving and philanthropic son.

Among the countless Hymn Books which have voiced the faith, trust and hope of English-speaking Christians for ages past, is a small octavo, printed in Edinburgh, in 1776, which bears the following title:

“HYMNS AND SPIRITUAL SONGS IN THREE BOOKS.

I. Collected from the SCRIPTURES.

II. Composed on DIVINE SUBJECTS.

III. Prepared for the LORD’S SUPPER.”

The binding on the copy of this Hymnal, which lies before us, might readily be attributed to an English binder, and the dark crimson morocco in which it is encased was undoubtedly an imported article, as also must have been the binder’s tools employed in its decoration. Its native workmanship is, however, established by the inscription upon the fly leaf, which certifies that this was “Hannah Boudinot’s book, bound and gilt at Trenton, 1785″.

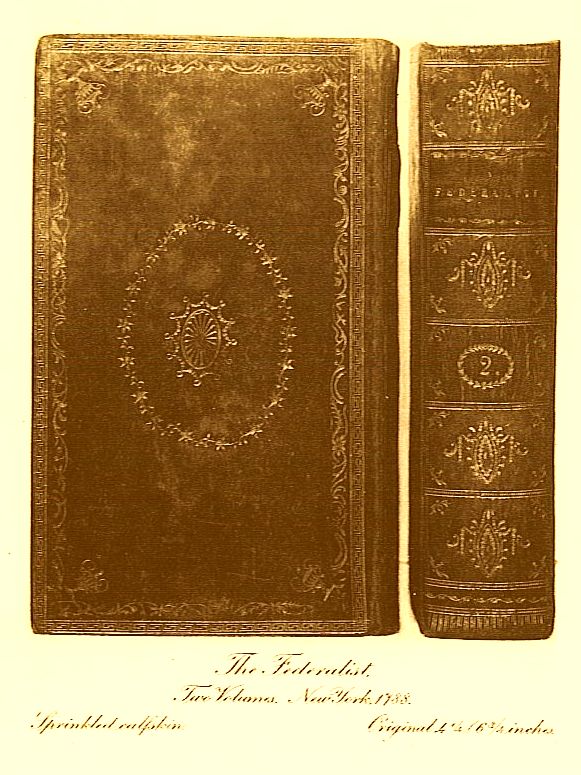

It is to be regretted that the artisan who, at this early period, was able to produce a binding of so creditable a character, remains unknown. He left his work unsigned, but this is as we might expect, for the articles of all times have been a modest race of men, quite content apparently to quietly pursue their calling and ” wake up each morning to still find themselves obscure.” The damask, velvet, and pigskin bindings of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were frequently stamped with the initials or trademarks of the binder or gilder, but the names which either rightfully or wrongfully we have connected with the several predominant styles of book-cover decoration, which have been pronounced ” as incapable of further development or of finer expression,” and of which we never weary, are seldom found upon the bindings attributed to these masters ; and in order to decipher the minute characters in which the signature of the modern article is all but concealed, at the foot of the inside cover, one almost requires the use of a magnifying-glass. In the same class and order of merit as the binding upon Hannah Boudinot’s Hymn Book, but of a different style of decoration, is the one upon a thick paper copy of the “Federalist” * in the Lenox Library, printed and bound, as the ticket within it attests, at Franklin’s Head, 41 Hanover Square,New York. It is in sprinkled calf, full gilt, as a cataloguer would describe it, the sides ornamented with a scroll border and an oval centre-piece, in the ” Etruscan ” style, so-called, a style common to the architecture, the silverware, and the furniture of the period, as well as to the exterior decoration of the covers of books which inherited its graceful lines, festoons and scrolls from the Greek and should be recognized as classical, but is generally known to us only by the much used and abused term Colonial.

* The Federalist : A collection of Essays written in favour of the New Constitution. 2 vols. Printed and Sold by J. & A. M’Lean, No. 41 Hanover-Square, 1788.

We find similar tools employed and a like design upon the cover of a copy of the American edition of Brown’s Illustrated Family Bible,* bound in red morocco, which material alone, elevates it to higher rank as a binding, than the “Federalist” bound in calf. The back of this cumbersome elephant folio Bible, is panelled in blue and yellow leathers, separated by bands of green, the whole richly tooled in gold ” a petits fers”. The upper panel bears the title of the book, the lower one, the name of the first owner, Mary Ellis, 1792, whose signature also appears upon the fly leaf, under date of August 12,1793. This mosaic binding, for such it is, was produced by Thomas Allen, book-seller, stationer and printer, as he is described in the New York Directory for the same year, and has his ticket on the inside of the front cover:

*THE SELF-INTERPRETING BIBLE. New York, Printed for T. Allen, 12 Queen Street, 1792. Illustrated with copperplate engravings by Tiebout and others.

“BOUND AND SOLD BY THOMAS ALLEN

No. 12, Queen Street.”

Thomas Greenleaf’s semi-weekly paper, ” The New York Journal & Patriotic Register” contains in the number for June 18, 1790, an announcement of this forthcoming publication which reads in part as follows :

” Brown’s Self-interpreting Folio Family Bible, embellished with a variety of elegant Copper-Plates, Being a genuine American Edition, the largest and cheapest ever proposed to be printed in the United States.

” Proposals for printing by Subscription By Hodge, Allen & Campbell, of N. Y. The Holy Bible containing The Old and New Testaments with the Book of the Apocrypha, illustrated with notes, &c. By John Brown, D.D., Late Minister of the Gospel at Haddington, . . . will be printed in large folio on fine paper, American manufacture, and on excellent, large and new type cast on purpose for this work.

“It will be completed in forty numbers, one every two weeks, price One Quarter of a Dollar or Twenty-five Cents.”

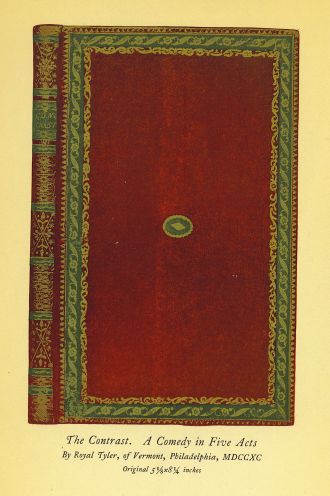

Quite as creditable to its author, and belonging to the same period as the binding above mentioned, is the one upon Washington’s own copy of “The Contrast” (Philadelphia, MDCCXC), a comedy written by Royal Tyler* of Vermont for Thomas Wignell, Comedian, now in the possession of Mr. S. P. Avery, a book made doubly valuable by having the great chieftain’s bold, clear signature upon the title-page.

*”THE CONTRAST was written by Royal Tyler of Vermont for Thomas Wignell, the comedian, by whom it was produced with considerable success in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. He took the part of Jonathan, written expressly for him, and a much more accurate representation of a real Yankee than any of the modern caricatures. It was published for subscribers only. . . . Royal Tyler was a genuine wit. He was aid to the Gov. of Mass, in the Shays rebellion, and followed the rebels into Vt., where he settled, and became eminent in public life. He was a lawyer and Judge. He wrote the ‘ Algerine Captive’ and many articles for the Polyanthus and other Journals – Dec. 3, 1876.” Copy of manuscript note inserted in the book.

It is a royal octavo, bound in a hard, close-textured, highly polished dark red morocco, the sides inlaid with green borders, with ornamental gilt scroll tooling. The back of the volume is elaborately gilt-tooled with small stamps, one of which is the acorn, a tool so frequently used by the Mearnes (the distinguished English article predecessors of Roger Payne), as to have become considered as reliable an indication of their work, as is the ” sausage ” pattern which appears upon so many of the bindings attributed to them.

Positive proof that this binding was executed in this country is lacking, but appearances and the circumstantial evidence in the case, point to that conclusion. This Comedy in five Acts by Royal Tyler, which claims to be the first ” Essay of American Genius in the Dramatic Art” has become exceedingly rare, notwithstanding the fact that as the printed list of subscribers shows, the edition consisted of at least 600 copies. It contains a curious and interesting frontispiece, engraved by Maverick,* after a painting by William Dunlap, which, as a manuscript note in the volume states, comprises five portraits, the persons being dressed as in the scene ; viz., Mr. Wignell as Brother Jonathan ; Mr. Henry as Colonel Manly ; Mr. Hallam as Dimple ; Mr. Morris as Van Rough; and Mrs. Morris as Charlotte.

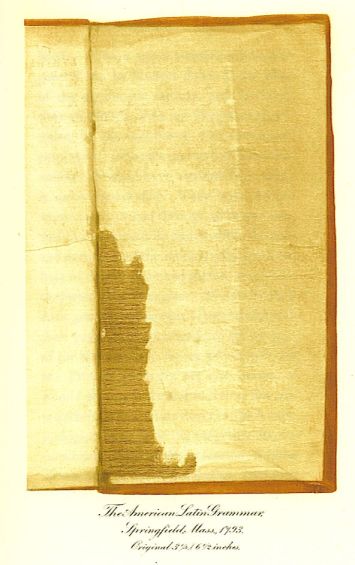

The “American Latin Grammar, or a compleat Introduction to the Latin Tongue,” which is shown in our illustration, is undoubtedly in its original boards, which are, as may be seen, as perfect, sound and true as when first applied ; and they have had to withstand the exceptionally hard usage, which falls to the lot of school and textbooks

*This must, I judge, have been Peter R. Maverick, the first of that noted family of engravers and copper-plate printers.

These oaken boards continued in general use by binders down to the close of the eighteenth century, and for some time afterwards, were not altogether superseded, by the cardboards now universally employed. The manner in which these thin veneers of wood have retained their shape is quite remarkable. They have neither warped nor cracked through all these years, and have successfully defied alike the cold and dampness of the mouldy cellars, and the heat of the sun-scorched garrets into which they were flung to neglect. Moreover, they have proved a somewhat better barrier than their pasteboard successors, to the ravages of the book-worm ; for are we not told that the Ptinidae generally are not borers of wood ? the chief mischief-maker in this material being that minute insect to which entomologists have given the altogether disproportionate name of Hypothenemus eruditus Westwood or the Hypothenemus bispidedus as it is described by Dr. Le Conte in Trans. Amer. Entom. Soc. 1868, p. 156 – Satis verborum !

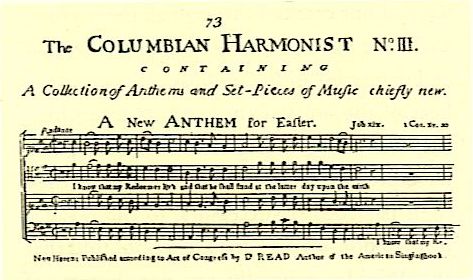

” The Columbian Harmonist , A Choice Collection of New Psalm Tunes of American Composition,” by Daniel Read, New Haven, Connecticut, 1793, which lies before us, is clad in its original homely but what has proved to be a fairly serviceable coat of brown sheepskin.

THE COLUMBIAN HARMONIST Number III

A Collection of Anthems and Set-Pieces of Music chiefly New

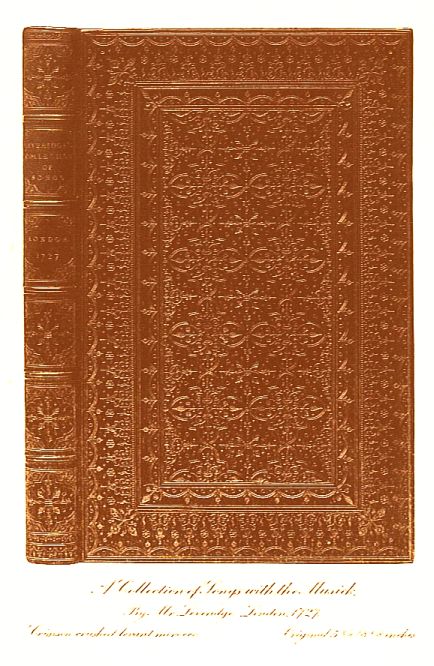

It makes no articleic pretensions whatever, and simply represents the rank and file of the bindings of the day. This quaint old Psalm Singer, which belongs to an age when the ” singing of psalms was an act of devotion, and not an amusement among the people,” “sings of simple pieties.” and is as plain and unadorned within as without; but doubtless the young men of the village church choir lifted up their voices as lustily in ” Old Hundredth” and the rustic maidens, their fair associates, chanted the Easter Anthem as sweetly, from the coarsely engraved score of this brown and battered “Harmonist” as if it had been cut on copper by a master hand, adorned with a frontispiece by Hogarth, and bound in French gros-grained bright red morocco, elegantly ornamented like unto the binding here displayed, which Francis Bedford placed, at a cost of nine guineas, upon another book of soulful melody, to wit, Mr. Leveridge’s “Collection of Songs with the Musick” London, 1727.

It must have been from a counterpart of this ” Introduction to Psalmody” by Mr. Read, ” fitly calculated for the use of Singing-Schools,” that the lank, long-shanked school-master, Ichabod Crane, instructed the sweet and buxom Katrina in the divine art of Music, whilst he was laying fruitless siege to the heart and hand already made willing captives, by the dare-devil Brom Van Brunt.

By the close of the eighteenth century, it is evident that the arts of printing and book-binding had come to a parting of the ways, and that the bindery, sanguine of its ability to walk alone, had begun to take upon itself the risks and responsibilities of a separate establishment. The New York City Directories of the closing years of the eighteenth century, contain the names of a number of individuals, among them the following, who style themselves simply bookbinders, although some of them were also stationers and printers:

John Black, 20 Little Queen (Cedar) Street.

Alexander Christie, 15 Cliff Street. Charles Cliland, 15 Madison Street. Peter Kirby, 44 Crown (Liberty) Street.

Robert Macgill, 212 Water Street.

John Reed, 17 Water Street.

Edward Wier, 52 Maiden Lane.

Robert Hodge, 38 Maiden Lane.

Benjamin Gomez, 32 Maiden Lane.

The advertisement of the last-named in the ” New York Journal & Patriotic Register” for the year 1791,reads as follows:

Book-binding carried on with neatness and dispatch.

Orders from the country will be carefully attended to.

That the typographers were, however, disinclined to abandon the field to specialists in Bibliopegy, is shown by this advertisement, clipped from the ” New York Journal” for December 21, 1791 :

Binding, Gilding & Blank-book Ruling

Performed in the neatest manner, and with the utmost

expedition at Greenleafs, No. 196 Water St.

In order to give the most ample

satisfaction to his customers in his

general business, as binding is closely

allied with printing, Mr. Greenleaf

has engaged a complete binder,

gilder, and ruler at an extraordinary

salary, and will engage that

everyone who may be pleased

to employ him shall be satisfied,

or no pay; and that all the work which

may be done shall be charged

quite as low as the current prices….

N. B.—A few well-dressed calf skins for sale.

– Wanted several hundred Sheep Skins.

These establishments were probably able to produce little beyond the mercantile bindings upon blank books, or work of a simple character, although some of the handsome bindings which, as we have seen, the binders of the time were capable of executing may have issued therefrom. Who knows? Admitting, however, that the chances are that these men plied their tools with little skill, all the same we are glad to recognize them as members in good and regular standing of the Guild of Book-binders. Little Brothers of the Honorable Order of the Glue-Pot and Pack Thread, we salute you !

An earnest and creditable attempt to improve the arts employed in the production of books, was made during the few short years of its existence, by the American Company of Book-sellers,* an association of book-sellers in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, founded in 1801, and dissolved in 1805. Annual fairs were held by this organization, in New York City, Philadelphia and Newark, N. J., at which premiums were offered for the best examples of paper, printing, ink, typography and book-binding.

In 1805 a gold medal of the value of $50 was awarded to one William Swain of New York, for the best specimen of binding executed in American leather. Mr. Swain, so far as I am aware, left no mark of identification upon his handiwork, so that we shall never know how meritorious were the bindings that sufficed to win for him, in the early dawn of the nineteenth century, this Bibliopegic prize. of an

* See Book-Trade Bibliography in the United States in the XlXth Century by A. Growoll. New York, 1898.

Books which contain the ticket of an American binder, are so few and far between, that I am disposed to make a note of even the unimportant example of the art of book-binding, to which is affixed the following label :

This little duodecimo Book of Psalms, printed in 1805, is bound in dark red morocco, gilt edges, with a simple decoration upon the back, which is sufficient, however, to lift it out of the grade of commercial bindings, and prove that Mr. Parson was not a mere cobbler of books. More, however, of an adept at his craft, was one Benjamin Olds, as is demonstrated by the binding in red morocco gilt on a copy of the By-Laws and Rules of the Society of the Cincinnati, Trenton, 1808, in which a modest little label one quarter the size of the following appears:

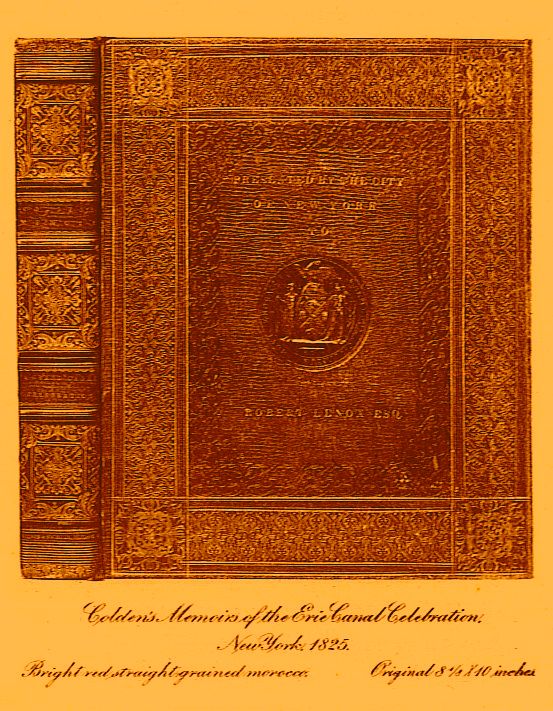

One of the most ornate signed bindings of this period, which has come to my notice is the one upon the presentation copy from the City of New York, to Robert Lenox, of Colden’s Memoirs of the Erie Canal Celebration, New York, 1825. It is bound in red straight-grained morocco, with wide rolled bands partly blind-tooled and partly gilt.

The panel back is elaborately tooled, and at the foot is the signature of the binders, Wilson & Nichols, whose names appear in Longworth’s New York City Directory for 1826-7, as engaged in business at Pine Street, corner of Broadway. The same directory contains the name of William Walker, 32 Eldridge street, at whose bindery or that of his sons, removed to Fulton street, the writer remembers to have had some of his earliest bindings executed. No examples of their skill, or rather the lack of it, are, however, now in my possession. It was a heavy and inartistic binding, only one remove – namely, that of the substitution of calfskin or morocco for Russia leather – from the bindings in which the firm encased the heavy day-books, journals and ledgers which, I judge, constituted their principal business, and won for the establishment the reputation it enjoyed as a bindery.

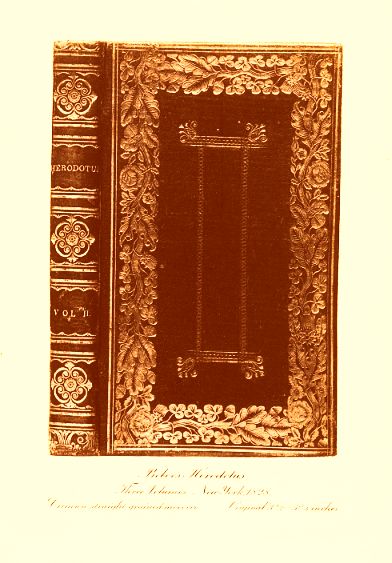

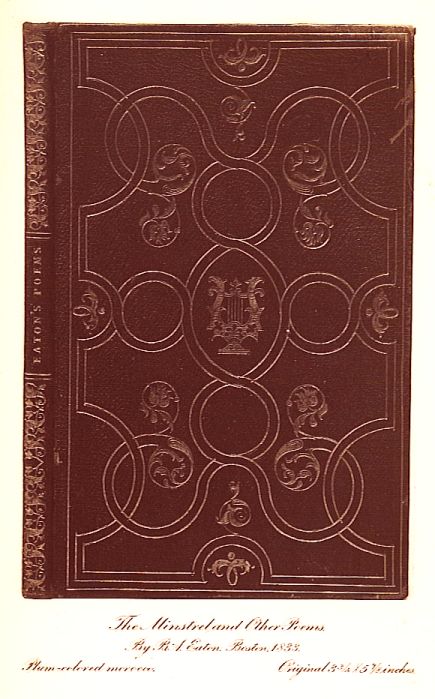

I regret that I cannot give the names of the binders of the little three-volume “Herodotus” New York, 1828,

which recently fell into my hands, and the copy of ” The Minstrel and Other Poems” by B. A. Eaton, Boston, 1833, belonging to Mr. Beverly Chew, for they are at least an approach to the bindings, which the collector accepts and places on his shelves because they are examples, if not elaborate ones, of book-binding practised as an Art, and not as a Trade.

The design on ” The Minstrel” is surprisingly Aldine in character, and cleanly tooled. Only bindings, in part at least, tooled by hand, rank as artistic in a bibliophile’s estimation, i. e., those bindings, the decoration upon which, is first designed and drawn upon paper, then transferred to the leather, and worked out either with small tools or by these in combination with rolls, fillets and panel blocks. It is not intended, however, by this statement to convey the impression, that a stamped binding is entirely devoid of artistic quality. In the production of a stamped binding, taste in design, as well as a high degree of mechanical skill and accuracy, may be displayed. The brass die which impresses the design, must be made, by the process known in the printing of engravings as overlaying,* to operate upon a perfectly plane surface, otherwise the impression in the leather will be of uneven depth to the absolute ruin of the design. The registry must also be exact, for an impression must first be taken in dumb or blind tooling, the same as in hand work. The gold leaf is then applied, and the book again subjected to the heavy heated press. The back if decorated when on the book, must be tooled by hand. A stamped back, in either cloth or leather, generally indicates that the cover is simply a machine-made case, attached to the book with glue, after the leaves have been sewn together, but the leather may be stamped with the design, before it is applied to the cover, and then drawn over the boards, which are laced to the book, as in fine tooled binding.

*Overlaying consists in pasting exactly where needed, successive layers of paper, underneath the tympan, or top sheet of the printing surface.

The principal items of expense in connection with a stamped binding, are the designing and cutting of the die. If applied to but one book, it might prove a more costly binding than one upon which the same design was tooled by hand. The economy results where long sets of books uniformly bound and decorated, are concerned. The following is an impression from a bookbinder’s stamp :

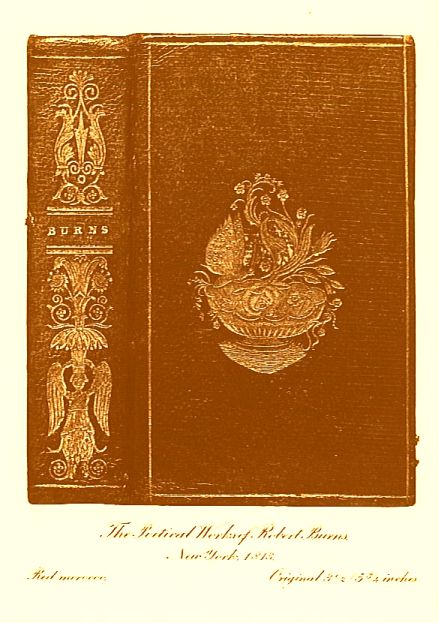

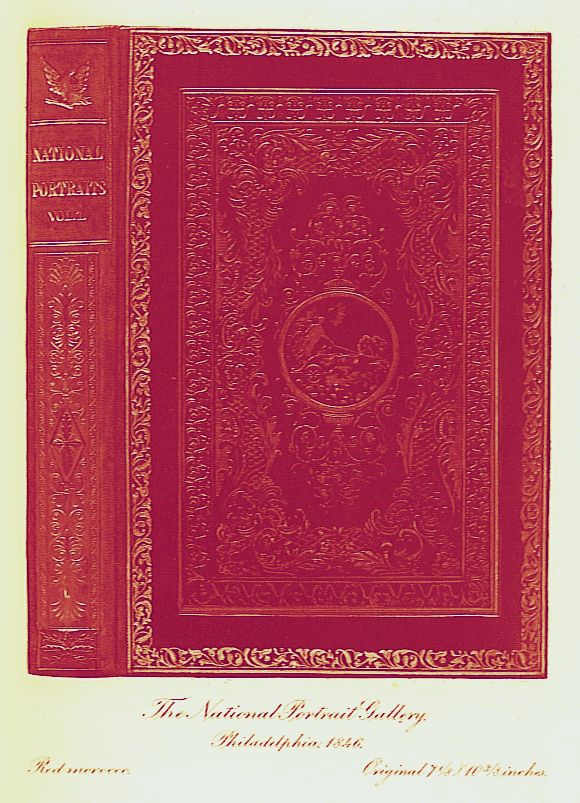

As an example on a small scale of American stamped binding, executed in the early part of the last century, we have reproduced one which covers a copy of The Poetical Works of Robert Burns, New York, 1813. The fac-simile of the ” National Portrait Gallery “* binding which follows, shows

*” The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans, 1846.” conducted by James B. Longacre, Philadelphia ; and James Herring, New York. Under the superintendence of the American Academy of the Fine Arts. 4 vols., royal 8vo and quarto. Contains 144 steel line engravings each accompanied by a short biographical notice.

how elaborate these stamped bindings became, at a later period, and how well they were designed and engraved.

The ” National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans” Philadelphia, 1846, is a book which deserves to be well bound, for it contains the finest cabinet-size steel-engraved portraits, ever executed in this country. This truth we have been slow to recognize, as also the fact, that the book is becoming difficult to find, for the reason, that for years past copies innumerable have been despoiled of their prints, by ” extra-illustrators,” to whom the four quarto volumes, with their nearly 150 very useful portraits, have proved a veritable goldmine. From both an historical and artistic standpoint the “National Portrait Gallery” was an important publication, and it is natural to suppose that certain sets of it would be entrusted to the hands of the best binders of the day.

The cover we reproduce shows how capable, both in design and execution, were the stamp-cutters of those days. The classical medallion centre-piece, links it in a measure to the highly prized bindings said to have belonged to Demetrio Canevari, physician to Pope Urban VIII.

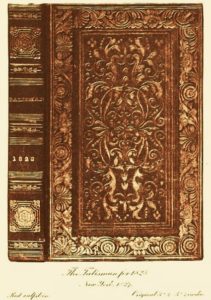

The period from 1820, to late in the fifties, was prolific of a class of books, the popularity of which, simply reflected a contemporary English taste, and shows that in matters literary and artistic, we were still in leading strings. These annuals, ” Offerings of Friendship,” “Tokens,” “Talismans,” and ” Souvenirs,” as they were sentimentally entitled, were issued by the publishers, in stamped cloth, morocco, or calfskin, overlaid with glittering gold foil.

They are equally, if not more valuable for their text and illustrations, than as examples of book-binding, for they contain some Bibliopegy in the United States of the best steel line engravings to be found in the books of their own or any subsequent period. It is the admirable work of such engravers as the Mavericks, Durand, Cheney, Balch, Pease and Hatch after paintings by Newton, Leslie, Inman, Morse, Mount and other American painters, of the first half of the nineteenth century, whose charming genre pictures – the writer ventures to assert – none of their successors have surpassed.

* Scene from ” The Merry Wives of Windsor” in the “Atlantic Souvenir” for 1828.

The Essays, Tales and Poems which these engravings accompany and illustrate, were contributed by some of the foremost writers of the day.

These Annuals, for years in the height of fashion, passed away with the Civil War, which changed for better or for worse the old order of things, in so many respects, and poorer books have taken their place ; for these gift books were honestly constructed, and the arts applied to them were legitimate and true, which is more than can be claimed for many, if not most, of the books that have succeeded them. These ” Gifts and Keepsakes” antiquated as they have become, are, however, no longer entirely neglected. They are sought by collectors, with some avidity; for they are interesting as mirrors of the simple living and quiet thinking of their age ; and, moreover, they have become somewhat scarce, and this is – shall we admit it ? – a sine qua non with the collector of every species.

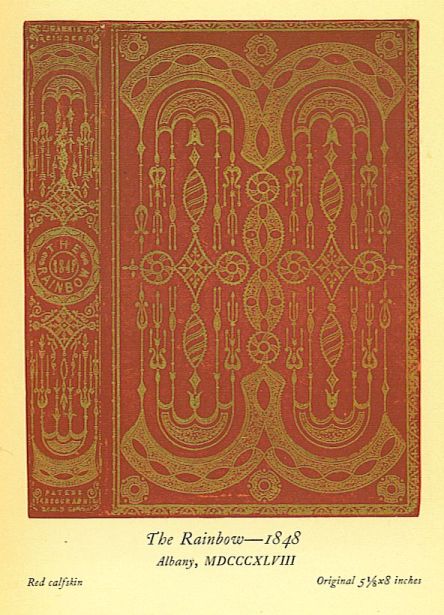

We now come to an exhibition of Yankee ingenuity applied to bibliopegy, which might be described as book-cover decoration made easy. But the name bestowed upon the process by its shrewd inventor, is ” Patent Stereograpbic Binding.” The presumed advantage of the process, was, I understand, the facility with which, by the application of different colors, to the compartments, mapped out by one and the self-same brass stamp, a surprising, and we may add a startling variety of effects, could be produced. This parody upon the Art of book-binding appears to have met with the disfavor it deserved, for I have never seen any example of it, save the one upon a gift book entitled ” ‘The Rainbow” published in Albany, N. Y., 1848, A. L. Harrison, Binder.

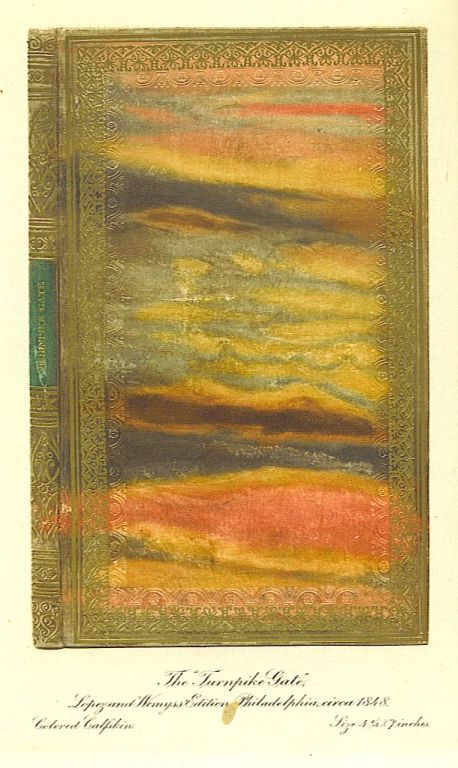

The variety of effects, in form and color, which mottled, marbled and sprinkled calf are capable of assuming, are as infinite and haphazard as those which cause the children’s eyes to dance with delight, when they turn with their impatient little hands the wonder-working wheel of a kaleidoscope.

The two most common styles of colored calf bindings are the ” Cambridge” in which the calf is colored over the entire surface, except a panel, left uncolored in the centre of the boards, and treed calf, which was so great a favorite with the late Francis Bedford, of England. These calf bindings certainly possess one paramount advantage, and that is the smooth and glossy surfaces they present, and which render them the most inoffensive and harmless of all bindings, to their neighbors upon the book-shelf. No calf binding, however, can hold up its head before one in crushed levant morocco, the ne plus ultra for the covering of a book.

A curious effect in colored calf, is shown in the cover of one of Lopez and Wemyss’ Prompter Books, a presentation copy to the Library of the American Dramatic Association, and presumably, therefore, as elaborate a binding of its kind as could at the time be executed. I find the same vividly colored calfskin upon a copy of Ackermann’s “Repository” London, 1809, which has in it a ticket which states that it was bound by Neal, Willis & Cole, Baltimore, Maryland.

For a more detailed account than that which we have quoted from Mr. Hazen’s ” Panorama of Professions and trades,” of the various processes of coloring, sprinkling, mottling and marbling the calf covers as well as the edges of a book, the reader is referred to the ” Hand-book, on the Art of Book-binding” by Joseph W. Zaehnsdorf (London, 1880), which is as complete a Manual upon the subject as the collector requires.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, sheep, and calfskins appear to have been the only leathers employed by American bookbinders.

Russia leather, so popular in England in the days of Roger Payne, came in vogue at a later period, but fortunately was never used to any extent, except for covering Merchant’s Blank Books, and the like, for it is the most objectionable of all leathers, for book-binding purposes, on account of its tendency to become brittle with age, and to part at the joints. The one redeeming quality possessed by Russia leather, is its fragrance,which, like properly cured rose leaves, it will retain for years.

Long after Morocco leather became a regular article of commerce between Europe and the United States, calfskin continued to be extensively used for the coverings of books, probably on account of its relative cheapness. Its use for fine or special bindings is now entirely abandoned, both here and in Europe.

The credit for having raised Bibliopegy in the United States permanently to the rank of a fine art, belongs indisputably to William Matthews, who was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1822, and died at his residence, No. 19 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, N. Y., April 15, 1896. He served an apprenticeship to a London bookbinder, and came to New York in 1843, where for three years he worked as a journeyman, at his craft of book-binding. In 1846, he began business on his own account, and in 1854 assumed charge of the bindery of the large publishing house of D. Appleton & Co., at the head of which he remained until 1890. The fine bindings he executed were mainly a relaxation, in which he indulged for the gratification of his cultured artistic taste and the accommodation of a few of his book-loving friends. So far as my knowledge extends, he never professed to make a business of special and elaborately tooled book-bindings.

The lecture read by Mr. Matthews before The Grolier Club of New York (of 112 And Kindred Subjects which he was one of the earliest, most interested, and valued members), March 25, 1885, and subsequently printed by the Society,* demonstrates his familiarity with the history of the art he loved and practised, as well as his acquaintance with its technique.

Of living American book-binders I have determined not to speak, for it would involve criticism and also comparison, which we are told is always odious.

The annual exhibitions of Fine Book-bindings held at our principal book-stores, to which I have already drawn attention, embrace examples of the best work of all the prominent American, as well as European articles, and those interested in the subject have in these attractive displays ample opportunities to examine, compare, and judge for themselves, of the respective merits of the men and women, who at present are following in the United States, the time-honored and beautiful Art of Book-binding.

Before them still lies the task of creating a style of book-cover decoration that can compare in originality and fitness with those of the Master Bibliopegists of past times, whose designs even Trautz, the greatest of modern French binders, recognized his inability to surpass.

* “Modern Book-binding Practically Considered.” A lecture read before The Grolier Club of New York, March 25, 1885, with additions and new illustrations, by William Matthews. The Grolier Club, MDCCCLXXXIX.