Practical Bookbinding

Morris Lee King

This essay was written principally for those who are interested in an amateur way in this subject or are contemplating taking it up, and at the same time are not able to come in contact with teachers of the art and others interested in it. I have not endeavored to cover the whole field, nor to go into the different methods in use in different countries. I have, however, endeavored to describe the processes through which a book passes from the moment the original casing is removed until it lies before us, well tooled, a thing of beauty.

Morris Lee King.

Editorial note:

First written in 1907 and 1908, this essay was never published in book form. It is presented here in its original text.

Copyright August 2001, bookbinding.com

The Beginning

BOOKBINDING in early times was carried on, the most part (as were so many for other useful industries), in connection with the religious orders. The monasteries were the chief centers for fine work in the way of illumination, hand-printed books and bindings of various kinds. The first good bindings of which I can find record came to Europe from the Levant?that is, from Arabia or Persia, gradually filtering through to Constantinople, to Italy, and so on, to France and Europe in general.

Before the art of printing was invented, however, bookbinding could scarcely be spoken of as having been widely known, because the only books then in use were printed with the pen, and copies were very scarce; they were to be found only in the possession of the monasteries and the very wealthy people of the time.

With the introduction of printing, however, binding became quite common, and early in the Middle Ages it developed into a fine art. The binders of those days, while they had more talent in the way of making designs appropriate to the text, did the technical work very crudely, the tools being made by the binders themselves, in many cases. This resulted in the finishing being done in what to-day would be considered a very haphazard and careless manner. At the same time these bindings still exist, and in many well preserved examples the condition of the finishing shows that it was not only solidly done, but that exceedingly good materials were used. It was Grolier, of Lyons, who first developed a special style of designs individual to himself. Many examples of his work are still extant, and his name is perpetuated by many societies of the present day. Since his day, binders of great repute have been more or less numerous, and various styles of bindings have been originated and are known by the names of such men as Le Gascon, Derome, the Brothers Eve, Jansen, Padeloup in France and Roger Payne in England.

During this formative period, leather was not as universally used as it is to-day, many bindings being made of wood, silver, velvet, cloth of gold and embroideries on various materials.

Of the modern French school, we need only mention a few names such as Trautz, Chambolle Duru, Gruel, Lortic, Marius-Michel, Ruban, and in England, Bedford, Zaehnsdorf, Riviere and Cobden-Sanderson. Aside from those mentioned, there are of course hosts of others, some of equal repute, as well as many who hope to achieve fame.

As the term “bookbinding” covers a variety of work, it is impossible in an article of this nature to treat it in all its varieties; so that it should be understood that the only kind of binding that will be here referred to is that known as ?extra first-class work,? and no attempt will be made to explain in detail the methods used in cheaper grades of work. Many of the processes described, however, may be used to advantage in simpler work; the extra expense involved, both as regards quality of material as well as extra cost of labor (owing to the time devoted to the work itself), is, however, prohibitive for ordinary commercial work.

Much of the work of the present day is well executed, as far as the technique is concerned, but many of the designs are imitations of the older and well known styles or inferior innovations. In many cases the books are over-decorated, owing to a desire to have a showy piece of work, this causing a loss of richness and dignity, due in many cases to over- decoration alone. Studying the work of the best binders of the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, one gets much information, and by constant endeavor may finally acquire a style of one’s own.

During the last few years we have seen in our country, in connection with bookbinding, the development of a new class of art workers, who may he classified under the general term of amateurs. This term, however, does not accurately cover all the persons who are thus classified. Of course the real amateur is supposed to be a binder who is working for pleasure and not for profit.

There are comparatively few of these, however, for many so-called amateurs are really semiprofessionals, engaged more or less in the production of bindings for profit. This applies both to teachers and those who are not engaged in teaching. The net result, however, of the growth of interest in this country has been to develop a certain number of binders who do work of the first class.

This, taken in connection with the professional binders who do commercial work entirely, renders it unnecessary nowadays for the lover of good books to send them abroad to be bound. While the best work in this country equals that done abroad, there are comparatively few binders who are capable of producing work that measures up to the standard of the best foreign binders. Aside from the scarcity of first-class workers, we must consider the question of cost; and as labor of all kinds is better paid in this country, it follows that binders here cannot, as a matter of fact, compete in price with those abroad, and it may be that this is one of the reasons why so much work is still sent to foreign countries.

The amateur who begins work with a view to becoming a good binder should in every possible way cultivate a liking not only for the special work he undertakes, but also for allied lines of art, and will do well to observe the following maxims:

1st.. Learn to care for really well-bound books by familiarizing ones self with such bindings and with fine editions of good literature, worthy of fine bindings.

2d. To make careful study of the details of mechanism, beauty and adaptation of fine binding; and also to gain accurate knowledge of the discrepancies and dangers that beset inferior work.

3d. To make perfection the goal of every effort.

To do ones absolute best with every stroke of work, from least to greatest, and to condone no failures save through renewed knowledge, ability and effort to do better.

The simplest textbooks for a beginner are:

Bookbinding, by J. W. Zaehnsdorf, Bookbinding for Amateurs, by W. J. E. Crane. , Bookbinding and the Care of Books, by Douglas Cockerell. Brander Matthewss , Bookbindings, Old and New, may be consulted with pleasure and profit.

While not a technical handbook, it gives one a brief view of the history and styles of the art. These are inexpensive and may be had through any bookstore. One of the first questions asked by the seeker after knowledge along this line is, what constitutes the difference between a well bound book and the ordinary book of commerce? It is surprising how small the percentage is of persons who have any definite knowledge as to what the elements of a good binding are. Knowledge on this subject has spread very slightly, and only among a very limited class of people; so it is always necessary to explain carefully to the inquirer just what makes this difference. The binding of a book is described in the two technical terms, forwarding and finishing.

Forwarding covers collating, cleaning, sewing, backing, head-banding, putting on the leather, everything, in fact, that prepares the book for decorating and lettering. Finishing comprises the designing of cover decoration, tooling of sides and back, as well as whatever decoration is done on the inside of the cover.

The ordinary book of commerce, which is generally sold in boards with a cloth or paper cover, is really not bound at all. The book is sewn by machinery, and the cover, which is technically known as a casing, is also made by machinery, in many cases being applied by the same machine. The connection between this so-called cover and the book itself is of the very slightest nature. The tapes or cords on which the book is sewn are held to the cover simply by one thickness of paper, and in some instances by one thickness of crinoline. The book is not strongly sewn, and it has no head-bands, save in some instances a strip of material (manufactured by the yard) pasted on in lieu of the head-bands, this being an imitation of the real thing.

A well-bound book, on the other hand, is properly sewn with linen or silk on linen cords; these cords are laced into each board in so firm a manner that it is impossible to remove the board without cutting the cord or tearing the boards to pieces. The head-bands are then worked on the book itself, these being made of a strip of vellum standing on edge and entirely covered with silk thread, each head-hand being fastened to the book in from three to five places, thus becoming an integral part of the book itself when it is finished. The boards are then covered either entirely or in part with leather, which is a further strong connection between the cover and the book proper. The leather may either constitute a half, a three-quarters or a full binding. The book is then properly decorated either with a simple title or with whatever elaboration or decoration is desired.

HISTORY:

Training

While it is a very simple matter to enumerate the different steps through which a book passes, each step must be carried out very carefully and accurately, else the result will be other than first class. From the time a book is given to a binder to be put in full leather until it is completed, two months or more may elapse; depending entirely upon how much tooling is done. It is necessary that plenty of time be given the binder, in order that one process may not be too quickly followed by another. Good forwarding is absolutely necessary for good finishing. Each process should be carefully carried out, as one depends upon the other, and a serious defect in one step throws the volume out of the first class, even though the other steps be well done. In continental countries the apprenticeship system which is in vogue in all arts and crafts results in producing forwarders and finishers who have grown up in the business, so to speak. They usually begin as errand boys, in a shop, at ages from twelve years up, so that by the time they become full-fledged workmen they have spent from ten to fifteen years in becoming thoroughly familiar with every process and method in vogue at the time. They also go through a period of three or four years careful instruction, both in the shop and in technical schools, acquiring not only a technical knowledge of their own particular craft, but being instructed also in knowledge most essential to any accomplished artisan, such as the elements of design of all kinds, instruction in the historical characteristics of each particular period, and other points of a similar nature.

One sees, therefore, that the making of an accomplished workman under this system is not a matter of picking up a new occupation in the course of a few months; on the contrary, he chooses bookbinding as his life work and really grows up in its atmosphere. With us it is somewhat different; we have not yet reached the point where a young man selects an occupation or where it is selected for him in early youth, and he serves in it as an apprentice; on the other hand, change seems to be inherent in the American atmosphere. This applies to occupations of all kinds. In foreign countries a man almost never changes his occupation, and in many instances follows his fathers occupation as a matter of course. Here we see about us constant change of occupation, even after a man has spent years of his life in fitting himself for a certain line. This naturally results in less careful work in all branches of art and trade, and to a generally unsettled industrial condition. No apprenticeship system is in vogue here except to a very limited extent, so that we constantly see men and women following an occupation which they have picked up on the spur of the moment with more or less success. We have, however, a number of professional binders in this country, and these should be divided into two well-defined classes: those who earn their living by forwarding and finishing in establishments where they are employed year after year, and those who may be called semiprofessional who work more or less steadily at binding, earning part or perhaps the whole of their living thus, but who cannot be properly classified in the same category as regards skill with the professional workmen. In both classes, however, we have some exceedingly good workers, but I notice that the best of them are those who are foreign born and have therefore gone through a thorough course of training, or are, perhaps, men and women who have been able to spend years working by themselves or abroad, and have thus acquired great skill.

There is another large class, however, who have taken up binding more as a matter of interest and pleasure. In this class, also, there are some who have done exceedingly good work, but the great majority are less competent. Let us hope that the day will arrive when we will be able to include many of them in one of the other classes. Up to about fifty years ago good binding was hardly known in the United States, but with the spread of wealth and especially of the traveling habitwhich Americans have developed to such a great extent knowledge on this subject has been acquired and spread about. This has resulted in the formation of many societies whose members are interested in fine books and, as a corollary, good binding.

The greatest cause, however, of the widespread interest which exists today has been the formation of various arts and crafts societies in all parts of this country. The older ones have, in many instances, become a great power for the spread of art knowledge of all kinds, including that of bookbinding. Many of them have special schools where binding is taught. There are a number of leading publishing houses also which have departments devoted to the production of fine editions, both as regards printing and binding. Several of them have even established special departments in their commercial binderies for the purpose of producing extra-fine work. One house in particular which I have in mind, has gone to the expense of sending a student abroad for a number of years in order that he might qualify himself by instruction under the best foreign binders for the position of Director of Fine Bindings in that establishment. The Grolier Club of New York, noted for its production of finely printed books, also extended its usefulness, by establishing a special bindery under the name of the Club Bindery. This bindery, however, being solely under the control of the club, is not open to the public, as all work done there must be done for, or through one of the members. This bindery is noted for the production of uniformly beautiful work, which I believe is due, to a great extent, to the fact that the personnel comes almost entirely from France and England, where they had years of training in the best binderies.

General considerations: I have known of a number of instances where attempts have been made to begin bookbinding with incomplete or very unsatisfactory appliances. It is not possible to do first-class work with poor materials or with an incomplete outfit, though expert workers can get along and do good work with fewer appliances than the beginner. It should therefore never be attempted. It is not only unsatisfactory from the point of view of practice, but it is very discouraging to the beginner to find the best attempts result in poor work sometimes not due to any lack of ability or effort, but simply to lack of conveniences. It is better to become familiar gradually with what is and what is not needed, to accumulate tools slowly, but not to begin definite work until a somewhat complete outfit is at hand, and one has acquired by study of works on bookbinding, and by conversation with practical workers, some idea as to ways and methods. It would seem unnecessary to give advice of this kind, but, as a matter of fact, I have known of a number of instances where intelligent people have begun to work under these conditions and have as a result become discouraged unnecessarily.

Design & Tooling Design:

There is no question but that the design itself is of as much importance as the quality of the work. A striking but simple design, based on sound principles of art, is much more valuable and much more effective than more elaborate work done in a haphazard and in artistic manner.I think it will repay every beginner to acquire some knowledge of the principles of design and to continue the study, especially endeavoring to get reliable information on the special principles which should govern every design made for use in bookbinding. As in the engraving of tools, it is necessary that the maker of designs for bookbinding should know the limitations of tools and their combinations as used in this work. A prominent architect who was formerly much engaged in designing book covers and type lays down these opinions:

Tool forms should be clearly manifest, no matter how intricate their combinations. Richness of design is readily obtainable without over elaboration. The fewer the number of tools used, the better.

Ornament should always be subordinated to use. Modern rather than historical designing should be encouraged. I quote in this connection, also, some remarks made by Mr. Philip Mason, of the Riverside Press, Boston: “I find the ‘architectural point of view’ -if I may so name it- a valuable one in the application of ornament to leather-bound books.

First of all, I believe that the designer should himself be a practical ‘finisher’. In no other way can thorough appreciation be had of the possibilities and limitations of the tools themselves, which are the component parts of the design. The design should be made with the tools. But ability to sketch freehand is of the greatest advantage in making ordinary patterns. Very much the same conditions which make for restraint and orderliness in architectural detail will be found to apply in the decoration of bindings.

Varying ‘textures’ and contrasting degrees of reflection are desirable and beautiful in gold tooling. The relation between the decorated and the undecorated surfaces should be carefully studied. Not infrequently, in an ineffective design, the unpleasant shape of the undecorated surface asserts itself in a way damaging to the decorated surface considered as a whole. It is a question whether the most pleasing of richly decorated bindings are not those whose elements of design-in other words, the ‘tools’are few in number and simple of form. Application of design (blinding-in): One of the principal things to be observed in the application of a design is to have it square on the board-that is, the outside lines should be absolutely parallel with the edges of the cover, which I note is frequently not the case. The slightest deviation from absolute parallelism will be apparent when the work is finished. It is not advisable, therefore, to “blind-in” the outside line or lines through the pattern. This outside line or lines should be marked on the leather itself with compass and folder and should be “blinded-in” separately. The paper pattern should then be cut to fit this line precisely, laid on the cover, and held by a weight at center; several spots at edges and corners should be touched with paste and the edges then pressed into the lines already made.

After it has dried, each portion of the design should be gone over with moderately hot tools-a moderate amount of pressure being used. After this is done one side of the design should be loosened by running the folder under the edge (after the pasted spots have been moistened), so that the worker may assure himself that all parts of the pattern have been impressed on the leather. After the whole pattern has been impressed the design is removed, great care being taken to immediately wash off any paste spots which may be left. The whole pattern has then to be gone over again with tools which are quite hot, being careful to apply them accurately in order not to “double” the pattern. After having gone over them a second time, it will be seen that the pattern is very clearly indicated, and it is now ready for the final “blinding-in”. Up to this point you will note that the leather has been worked in its dry condition. Careful inspection will show that the leather just outside the edges of each impression is “pulled down” toward the impression, instead of being at its normal level, and making a clear cut impression for each part of the design. In order to correct this and to render permanent the impression already made, it is necessary to dampen the design with vinegar, allowing from fifteen to twenty minutes to soak in thoroughly; the whole pattern is now worked over again, this time with more care, if possible, than before, and with tools which are not too hot to rest against the hand.

Much care must be taken as to the heat of the tools during this operation, because the slightest excess of heat, combined with pressure, will cut through the leather, or at least burn it, so that the pattern may be spoiled. The principal reason why it is necessary to moisten the leather and go over the pattern again is, that if this is not done, the impression “blinded-in” on the dry leather would almost fade away on the application of any moisture, such as “glaire,” or at least become so indistinct that precise tooling would be impossible. It cannot be too forcibly impressed on the worker that careful, precise “blinding-in” is absolutely indispensable. The final results of thorough “blinding-in”, over careless work, are very similar to the results attained by the careful as against the careless cultivator. The one cultivates his land thoroughly, going over it again and again, to put it into the very best condition for producing good crops. The other is satisfied with careless preparation of the ground, and the result is that his crops not only are small, as regards quantity, but poor, as regards quality. The same thing applies to thorough and superficial work as regards the operation of blinding-in. Blinding-in of back: All designs for panels of back should be laid out from a central perpendicular line.

Having laid out the pattern, the paper is cut at top and bottom of panel, three and four inches being left at each side. Place the book- a pressing-board on each side-in the finishing press. With a folder make a slight mark on each panel at the exact center of back. The paper strip with panel design is now laid across one panel and the center line of the pattern adjusted accurately to the guide marks just made on the latter. Holding it firmly in place, the ends of the strip are touched with paste and fastened to the sides of the pressing-boards. It is now blinded-in, and the other panels treated the same way. The lettering on the back should also be laid out accurately on a similar strip of paper and blinded-in most carefully; much care should be taken to have it in the exact center of the back. Blind tooling: This is also known as “antique” monastic style. Blind tooling is simply blinding- in the design (as if for gold work), and instead of using gold, changing the color of the leather itself (in the impressions) to a brown or black. This is done by dampening the leather after the design has been impressed and going over the damp design again and again with tools warm, but not hot, the object being to outline the design either in brown or black. This is really done by singeing or scorching the leather under the tools. The color and depth of the pattern or design should be uniform over the whole pattern. When the blind tooling is completed, let the cover dry thoroughly, and then work the design again with tools much hotter than before; this polishes the leather in the impressions.

Studio, Machines and Tools Space needed:

Living in a crowded city as I do, and seeing a good deal of work done by others where space is valuable, I have of necessity devoted considerable thought to economy of space. While this is not a matter of importance to all, still I think a majority of amateurs are obliged to consider the question. We are not all fortunate enough to have a special workshop. All the work that I have done has been accomplished on two tables or benches, four feet long by two feet wide, fixed in front of two windows.

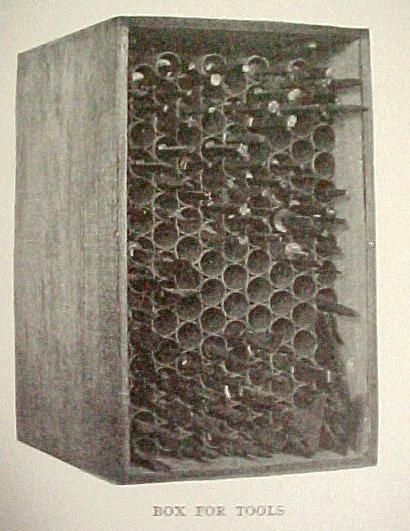

Three feet is a convenient height, but this depends upon the height of the worker. One table is devoted to forwarding, and has under it shelves and racks for holding pressing-boards, paring stones and the miscellaneous paraphernalia needed. The edge next the window has a raised ledge of six or eight inches, on which are arranged knives, straight-edges, etc. The other table, used mainly for finishing, holds the gas stove, etc. Above it on a side wall a small set of shelves gives room for the various small items needed in this branch of the work. This table has a number of drawers for storage of papers, leathers, gold cushions, etc. The raised back edge of the forwarding table, with an adjustable support on the front edge, holds the cutting-press when in use. This is not convenient, however. When possible, the usual “tub” should be on hand for daily use. The press, be it the usual standing-press or a strong letter-press, must stand on the floor or on a separate block. Almost all the processes of binding may be carried on by artificial light, but in this case it is well to have two lights, so as to avoid strong shadows. I advise strongly, however, against using finishing tools under artificial light. It can be done, but it is difficult and not satisfactory even for an expert worker.

Tools and necessary appliances: The most important thing is the cutting-press and plough. The standard size made for use in commercial work of all sizes, is too heavy and clumsy to be used by a beginner. A smaller size is made and may be ordered through the regular dealers. It is much lighter and is easily handled and answers all purposes, as it takes books up to sixteen inches in length. The price is the same as for the standard size. As it is always made to order, it takes a few weeks to get it.

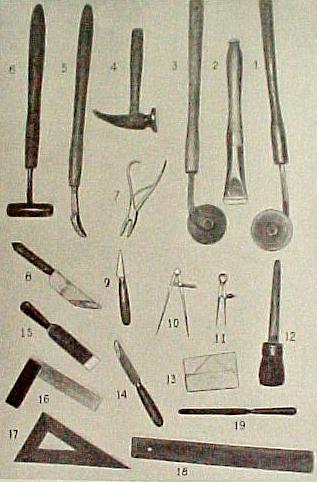

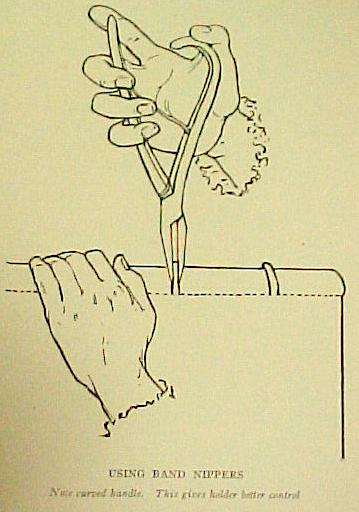

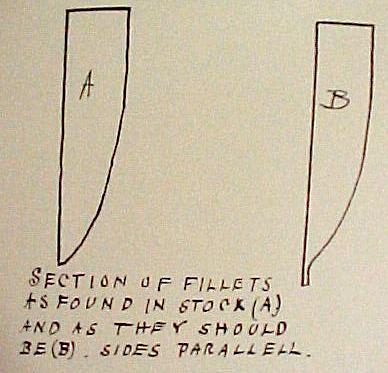

TOOLS: 1 and 3, Fillets; 2, Agate Furnisher; 4 Hammer; 5 and 6, Metal Burnishers; 7, Band Nippers; 8 and 15, Paring Knives; 9 and 14, Paper Knives; 10 and 11 Compasses; 12, Paste Brush; 17 and 18, Drawing Tools; 19, Gold Knife; 13 Pattern for cutting corners of leather in covering

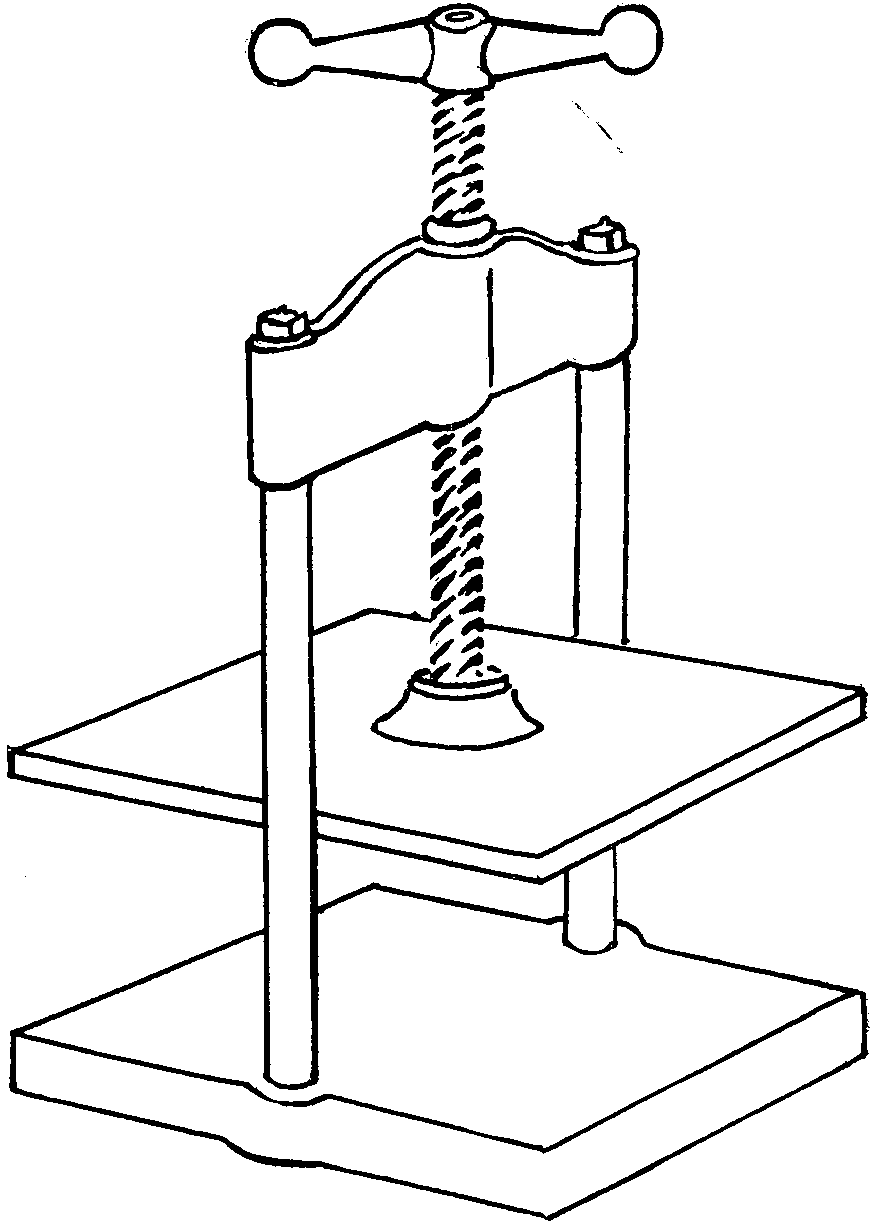

The standing-press may be of wood or steel and ranges in price from twenty dollars up. An amateur may, however, get along very well with a strong letter-press. I know of a number of amateurs in New York who are doing good work and who use only a letter-press. Another amateur living in the suburbs has converted to her use a small press formerly used in a cider mill.

Finishing Press: A press of this variety, 14 to 16 inches between the screws is ample for the beginner. It should be lined with skiver on the inside and on the upper surface. This is convenient in many ways, especially when small books are being handled.

Skiver is the inner or flesh surface of the skin which is left ,when leather is “split.” It is very useful for many purposes and can he had for a trifle Knives of various kinds are needed as follows:

Paring knives: Two at least are needed, the one most useful is shaped as shown in the illustration (a); another shown at (b) is known as the French style, and is very useful in paring out backs and also for finishing the paring of edges; it renders them more even. One knife, to be kept only for the cutting of paper, of the shape indicated herewith should be in the knife rack. Only the rounded edge should be sharp. One or two knives with blades of this shape should be provided, also, for miscellaneous use.

Whetstones: All cutting apparatus should be kept in good condition, as a torn edge of an end paper, a section, a piece of leather, caused by a dull knife, may result in hours of irritating repair work, and even then be unsatisfactory. One good oilstone and an ordinary whetstone (to be used with water or dry), a strip of sole leather, 2 or 2 1/2~ by 14 inches, coated with oil and fine emery powder, are necessary. The other laid on the table when paring, one end under the right edge of the paring-stone, is in constant use when paring leather.

While it is necessary to have knives ground only from time to time, it is constantly necessary to sharpen up the edges, and even a novice may learn in a short time how to use all the above. It is absolutely necessary to know how in order to save ones self constant annoyance.

Machines, Tools & Supplies

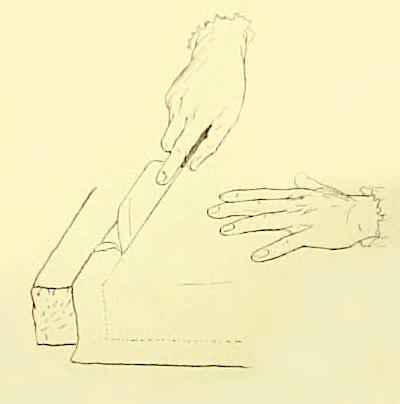

Covering pad: When leather is well moistened it is easily marred by rough handling or contact with any hard object. Putting in leather should be done on a soft surface. It is well, therefore, to cover a full-sized sheet of mill-board with a thick piece of skiver. Place this on the bench and rest the book on it when putting on the leather. A hole cut through one edge allows it to be hung on the wall when not in use.

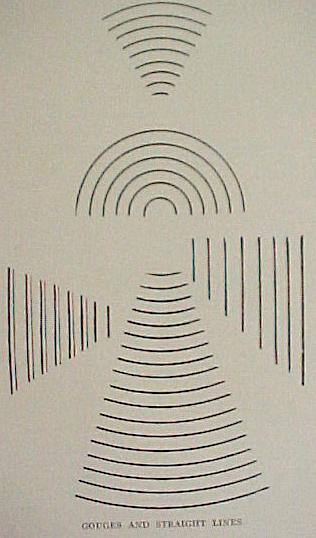

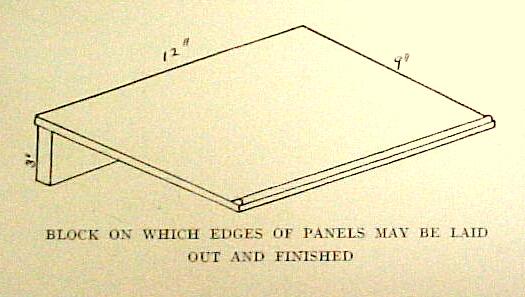

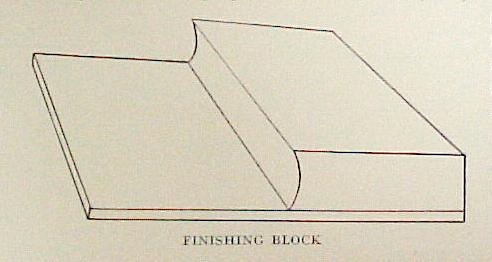

Burnishers: The sizes most useful are 9 by 12 inch, 12 by 24 , but one can get along with one only. (See illustration.) Another (see cut), covered with skiver, is most useful in laying out and blinding in the straight lines along the sides of the panels. With the back at the upper part, the cover is raised two inches or so to a level, a paperweight or similar object slipped under it. Having marked at head and tail where the outside lines of the panels are to come, a straight-edge is laid on the cover, and with a sharp folder the lines are marked on all the panels at once, so they are exactly inline. The ruler may also be used by the beginner for the preliminary blinding-in of these lines.

Two or three small but heavy weights are needed at all times. They may be small steel blocks such as are used in blocking presses, or of lead. The latter may be had at any large printers, being run out of old type metal. A very convenient size is 3 by 6 inches by 1 inch thick. They should be covered with skiver or stout paper. This is the technical name under which the various kinds of cardboard and pasteboard are known in the trade. There is a great difference in quality. The ordinary domestic board is not worth using for good work. The very best quality of domestic board may be used from time to time, but for really first-class work it is best to use the best grade of English or French board. Mill board is found in the market in bundles of 100 pounds, the number of sheets depending on the thickness of same. The size of the board is about the same (average 20 by 28 inches) in all cases, but the thickness varies very much and is known by numbers. These boards, both the domestic and the foreign qualities, can be purchased at various dealers in supplies of this nature in less than whole bundles, so that it is advisable for the beginner to get a few sheets each, say of numbers 63, ,30 and 21. As all boards should be lined before using, it is advisable for the amateur to do this at one time and line the whole stock in hand (if not too great a quantity) in order that they may be ready, and that this operation need not be done from time to time, as it is just as easy to line a number as it is to line one.

Sheets of plain white paper either an ordinary quality of writing paper or other good quality of light paperof the same size as the hoards should he spread on the table and the top one thoroughly pasted with a fairly thin paste. The board to be lined is stood up slanting in front of the operator, the sheet of pasted paper taken by two corners and laid against it. It may now be laid on the bench and smoothed out thoroughly with a brush or a soft pad. Should there be any wrinkles, the nearest corner may be lifted and then let fall back again, smoothing the wrinkles out at the same time. Each board as it is lined is stood up to dry. It will he found that after they have dried they are drawn towards the side lined and this lined side is the one which makes the inside of the cover. Some binders are in the habit of lining both sides of the hoard and in this case one side receives two thickness of paper the side which is covered with two thickness is the one which forms the inside of the cover. A double lining of this kind is also useful when the board is slightly too thin for the purpose intended, and this strengthens it and also increases its thickness somewhat. This is a very important item in this work, it is necessary that it be of good quality and kept in good condition. The amateur worker will do well to purchase it or make it in small quantities only, so as to have it fresh at all times. Ordinarily paste is made by mixing flour and water and boiling it to a somewhat stiff consistency. The following methods are an improvement, however.

Paste for ordinary use: Take one-quarter pound white flour, one-half teaspoonful powdered alum; mix and stir in enough cold water to make a thin gruel. With a spoon or flat wooden spatula rub it up till all lumps have disappeared. Add cold water to make about a pint, and heat it i ly in an enameled saucepan. It should be brought slowly to the boiling point, stirring from time to time. Let it boil a few minutes, stirring briskly the while.

Paste for mending (Cockerell): One teaspoonful ordinary flour, two of corn meal, one-half teaspoonful of alum, cold water three ounces. Stir thoroughly with a wooden or bone spoon. Let it come to a boil slowly; it should be kept at the boiling point a few moments, stirring well at the same time; if too much heat is used it tends to turn it a dark color, so this should be avoided. A few grains of salicylic acid stirred in will aid in preventing it from turning sour.

Rice paste: Mix a few spoonfuls of rice flour with cold water and boil slowly. A little alum or a few grains of salicylic acid stirred in will keep it fresh a long time. Commercial paste: In all large centers paste is found on sale; this is made commercially for hinders use and may be had in small quantities. It is usually well prepared and is of good quality. In using paste the following points will he found useful to the beginner. Paste should always be kept in wooden, glass or enameled ware containers never in any vessel composed wholly or partly of metal. When thinning paste use water in small quantities and be sure to rub it up thoroughly, so that all lumps disappear and it is smooth. There is nothing more irritating than to be bothered (in the midst, perhaps, of a troublesome piece of work) with lumps, or loose hairs from your brush. Use a large brush for paste. Accustom yourself to take up paste on the second or third finger of right hand, and not on the index finger. It is often necessary to use the latter for other purposes at the same time. When pasting a narrow edge always place a clean straight edge of paper on the page, so as to expose only the part to be pasted. This makes a straight edge and protects the balance from soiling.

When pasting a number of edges at the same time, place them on each other and fan them out so that just enough of each edge is exposed; then place a strip of paper on the upper one (as explained above) and paste the lot. Paste should be used quite thick on leather and when pasting narrow margins, such as end-papers. For lining boards and pasting large surface of paper it should be thinner to run easily.

The majority of fine bindings are made of Levant morocco. Other kinds, such as seal, pigskin, etc., are used from time to time, but comparatively infrequently. There are many qualities of each kind of leather, but nothing but the first grade should be purchased. Although almost all of the better grades of Levant morocco are imported, we find that the American market does not as a rule receive the very finest grades of leather, these being used up in the country of their origin, and a comparatively small proportion is ever exported. At the same time leathers of a good quality can be purchased here. Some few years ago general complaint was made by librarians and others that the leather used of recent years deteriorated much more rapidly than that which was used in earlier times. An investigation was set on foot by the Society of Arts, and its report (for details see Bookbinding by Douglas Cockerell) showed that this was probably due to the introduction of chemical tanning processes instead of tanning by the use of vegetable products as in former times. Several leather manufacturers in England decided to change their methods and to produce leather which was tanned entirely by vegetable processes and this leather is known as acid-free leather, each skin being stamped to guarantee its quality. This leather does not cost materially more than a first class article of the ordinary type, so that it is advisable to use it wherever possible. This acid-free leather may be had now in New York, one of the members of the recently formed Guild of Book-Workers having it on sale. *As a matter of fact, the quality of materials used in fine bookbinding should always be of the first class, because the item of extra expense for each individual book, for materials alone, is so small, and the labor devoted to each hook so large a proportion of its ultimate value, that it is not worth while risking a good product by using anything but materials of the very best quality. Of recent years it has become quite customary to use leather which has been split; that is, a certain thickness (known as skiver ) is split off the inner surface of the skin by a very ingenious piece of machinery. The objections to split leathers are many; only a few need be mentioned: Much of the strength of the skin is sacrificed, and only the outer part of the skin, which has been hardened by the tanning process, is left. This is not so tough as the inner layers, which are also quite necessary to make a firm resisting medium for tooling. Again, even when split, the skin may still be too thick for a very small book and too thin for a heavy volume. The amateur is tempted to have his skins split, as he usually dislikes the drudgery of paring a thick cover. By selecting skins of varying natural thickness much unnecessary work of this kind may he avoided. When I began binding I had my skins split, as I liked the thinner leather not appreciating the damage I was doing and the difficulties I might have later on, in the way of unsatisfactory tooling, etc. I strongly advise the beginner to use leather of the natural thickness, providing himself with plenty of paring knives (of the very best quality), and to learn immediately how to pare a cover rapidly and properly it is not difficult under favorable conditions. Again, however thick the cover may seem when handling it, much of this thickness is lost when the book is squeezed (damp) in the press before tooling, to consolidate it and make a firm, smooth surface. I have seen leather lose from one-third to one-half its original thickness.

Preparing for Sewing

Trimming sections:

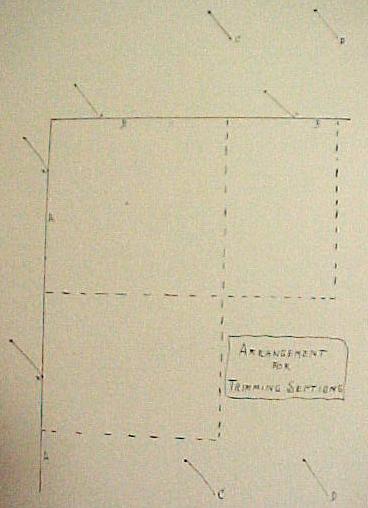

Books are often rebound where the sections have been irregularly folded, so that the fore edges and tail show great differences in depth of sections. It is necessary to trim them to some standard. After the sections are ready for sewing, take the book between the hands, knock the back straight, then reverse and do the same at the head, taking care to keep the book straight; then turn the head toward you, sight along the fore edge and select one section about midway in width between the widest one and the narrowest one ; take the section out and measure it accurately with compass from back to fore edge, then knock the book into shape again; sight along the tail and select another section to get the average height. Take this measure also.

We now have a standard for height and width, to which all sections should conform; none should exceed these measures, though some may of necessity fall short. We are now ready for trimming. If we have a regularly graduated paper- or board cutter, this is easily done; no machine, however, being the rule among amateurs, other methods must he used.

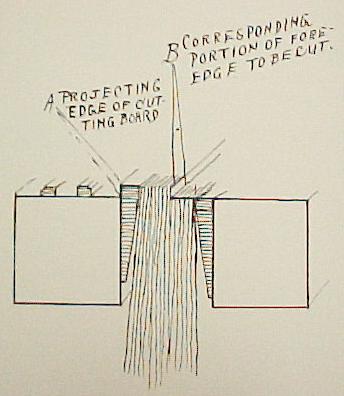

The following is simple, easily arranged and within the reach of everybody: A cutting board, or square of millboard, considerably larger than the section, is laid on the table. Two lines are drawn -A and B- at right angles (use steel square), and at the points indicated by X strong pins or fine wire brads are driven. Care must he taken that these pins stand straight and lean neither to the right nor to the left; the points should go through the lines not alongside. (It is preferable to use a sharp folder to make the lines, as pencil lines are always of varying width and should never be used when accurate measurements are required.) The line A being used as a base line, two points are determined (C C) by the measure previously selected as the standard for the width of the sections. Pins are driven here also. We are now ready for trimming the fore edge. Take one section at a time, place the back against the line A, head against the line B. Place a straight edge on fore edge of section, the straight-edge resting against points C C, and with a very sharp paper knife cut off whatever shows beyond the straight-edge. Some sections will fall short and need no trimming. The fore edge is thus equalized.

We now take two more points (D D), using the second measure previously decided upon as the standard for height. Drive two more pins here. Now place each section back against line B, head against line A. With the straight-edge resting upon the section as before, and against points D D, the tail of each section is trimmed, if it projects. Always keep the sections in their proper sequence. It will now be found on knocking the book into shape that the fore edge and tail present a more regular appearance. It is not desirable to cut much off the fore edge and tail (unless edges are to be full gilt), especially in books printed on hand-made papers.

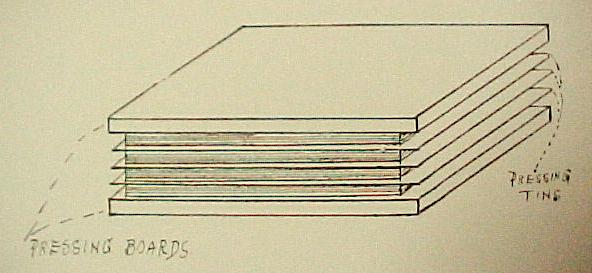

In order to have a good surface to trim on, it is advisable to place a strip of zinc on the cutting line several strips of zinc of various widths and lengths are very useful to have on hand for this and similar purposes. The sections may also be trimmed by cutting a mill-board accurately the exact size decided upon, and placing it on each section in order; cut off the projecting edges. This method is satisfactory in expert hands, but the former gives better results in the long run. Beating: Binderies should be equipped with a heavy iron or stone heating block with a beating hammer. The amateur, however, may make shift to do with a heavy lithographic stone resting on a somewhat yielding bed, and the beating may he done with a heavy backing hammer. After the sections have been cleansed of glue and collated, the book should he thoroughly beaten in order to more completely consolidate itthis is especially necessary if it is a new book taken from the ordinary casing. If a thin book (say 1/2 to 1 inch in thickness), all the sections may be beaten at once. If thicker, half of it may be taken at one time. After each half is beaten, join them again and beat the whole book once more. Care must be taken to beat each portion evenly and strike squarely so the edge of the hammer-face never touches the sheetsif it does it will mar them. Beating should be practiced on some useless books. The sections may now be knocked up so the back and head are quite square, placing pressing tins between every five or six sections; the whole is then put in the standing press under the greatest possible pressure and left at least twelve hours.

FORWARDING: Sewing

Three weights of Irish linen thread, Nos. 15, 18 and 25, will answer for almost all books. If there are many sections and they are thin, a light-weight thread is used. If the sections are thick, or very few in number, heavier thread may be used. It should always be borne in mind that the back will contain, when finished, as many threads as there are sections, and the back, when finished, should not be materially thicker than the rest of the book. Silk of various weights and colors may also be used in fine work; it should always be slightly waxed before using.

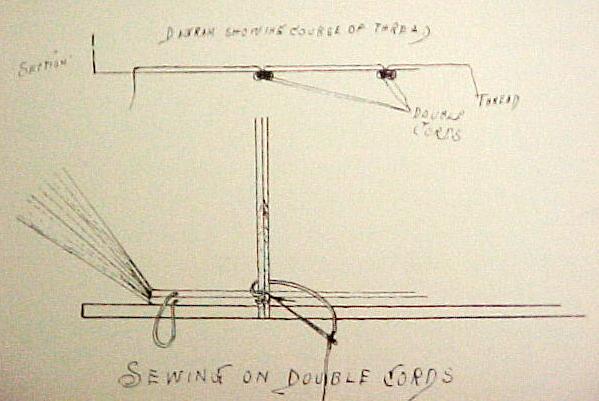

The book should now be knocked up between two pieces of board about the same size, the square being used on the head, to see that it is about square; it is then screwed in the cutting press. Old covers will be useful here. The back must now, by means of the compass, be divided into proper squares. It is customary to divide an ordinary octavo into six panels, making five bands, the four central spaces being equal to each other, the one at the head a trifle longer, the one at the tail a bit longer than the one at the head. Each binder may have his own ideas as to proportion and, indeed, as to number of hands. The points where the cords are to come being determined as above, the square is used and a heavy pencil mark made across all the sections where each cord will fall. If sunken cords are to he used and false bands made, then a fine-toothed thin saw is to be employed, sawing on the lines just made, until the saw-cut will barely show on the inside of each section when opened. Care must be taken that the cut be not too deep (better have it too shallow) and that it is not deeper on one side of the back than on the other.

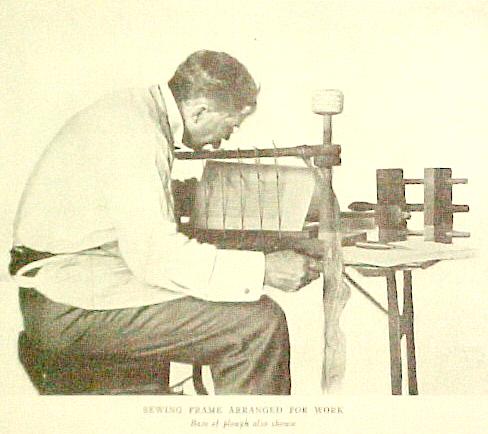

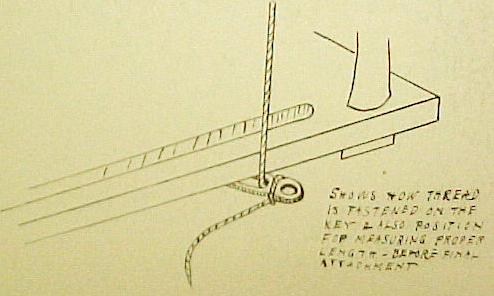

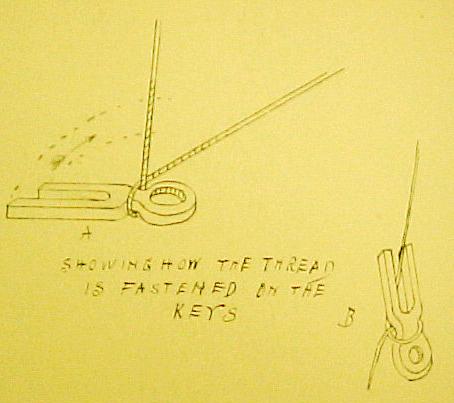

If raised cords are to be used, no sawing-in is done; but it is very useful to make a shallow cut instead with a sharp, thin knife, so that less difficulty is experienced in finding just where the needle is to pass through the sections when sewing. Over handing outside sections, to give strength where most needed. The first and last section should now be over handed with fine linen thread, with stitches one-quarter inch apart. After this is done these sections should he placed on the beating stone and tapped slightly to bury the threads somewhat in the paper. Kettle-stitch: For both styles of sewing, however, a mark must also be made about one-half inch from head and tail and also sawn (but very slightly). These are for the turn of the thread in sewing, making what is known as the kettle-stitch. The sewing frame is now prepared. If the book is sawn in, thin linen cords are used; if not sawn in, heavy English or Italian cord is needed. The number of cords in each case is the same. The proper number of cords are now fastened in the frame and tightened up (see diagram).

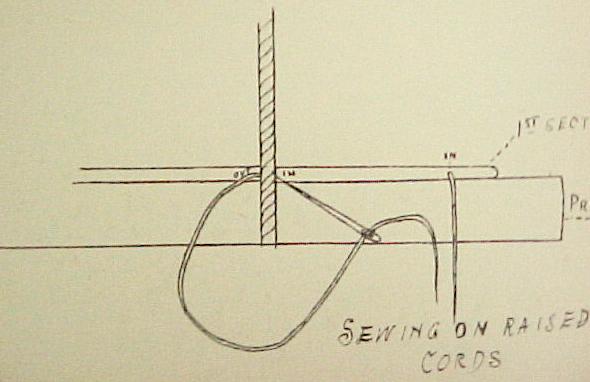

Place against the cords a thick pressing board, larger than the book to be sewn, so that the first section is raised up somewhat and handled more easily. The first section, being over-handed, is quite difficult to sew. It should be opened in the center and the needle passed through from center to back wherever a cord is to come (this preliminary work makes it more easy to pass the needle when sewing). Now lay this section, face down, on the frame, so the cords lie against the marks or cuts made on the section. The cords are to be adjusted to fit this spacing and then are tightened up. Sewing on sunken cords: As the operator sits before the frame the back of the section is toward him, head to the right. The left arm passing around or inside the left upright, as may be most convenient, the hand is placed in the center of section, holding it partly open; the right hand now passes the threaded needle into the kettle-stitch opening at head of section, is received by left hand and passed back through the first cut, the needle end coming out between the kettle-stitch and the first cord.

With the right it is now passed around the cord and back through the same cut. With the left hand it is again passed out through the next cut, around the cord and back, drawn up snugly from time to time so the cords are held tightly against the section, until it is finally passed out through the kettle-stitch opening at the tail. The next section is now laid on the first, held open with left hand, the needle passed through the kettle-stitch opening (next the tail), drawn up snugly and this section sewn as before.

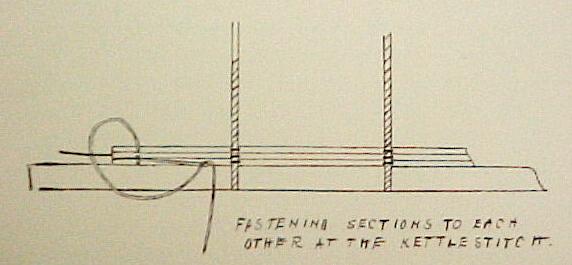

Before passing to the remaining sections it is necessary to fasten the loose end of the thread which is still projecting from the first kettle-stitch opening. Steady the two sections with the left hand and pull each thread tight; then tie them together (they tie better if slightly moistened), cut off the original loose end and proceed with the sewing. The needle now being passed into thread drawn tight, it will be noted that this binds the ends of the three sections together. On emerging from the kettle-stitch at the tail of this section, the needle is passed between the second and first section (inside the thread lying in the cut for the kettle-stitch) and out toward the tail, the thread now forming a loop. Pass needle from below upward through loop and draw tight; this fastens the ends of these sections together. [sewing4.jpg] The ends of all sections must be tied to each other in this manner; but care must be taken not to draw the thread too tight, else the head and tail will be thinner than the central part of back, and will be so leaving a clean, straight strip of paste on the section. Let it set a moment or so, then bring the first section over, close it but do not use much pressure over the paste. Be sure the back edges of the two sections are quite evenly adjusted.

Treat the last section in a similar manner. Place the book between two pressing boards with a weight on it and leave for several hours, or overnight. The object of the two cardboard slips is to bring the weight on the pasted portion only and make a solid union. If this is not well done, it is liable to come apart when the book is opened. This also hides the thread used for Over-handing.

End papers;

These may be white, plain paper, as much like that of the printed page as possible, but often they are made of a colored paper harmonizing with the color of the leather used. While any firm paper of good quality may he used, it should be of tough fiber, so it will not give way in the hinge or during manipulation. Hand-made papers of many kinds are in the market. Of the best and most decorative are those known as the “Morris” papers of English manufacture. Having selected the quality to be used, cut two pieces, which, when folded, are somewhat wider in both directions (say one-half inch) than the section of the book. After folding them -with the plain side out- line one side with white paper like that of the book itself. This lining paper should reach not quite to the jolted edge. Leave a strip about one-eighth inch. Place between two sheets of blotting paper, give them a nip in the press and stand up to dry. Now take two pieces of the same paper just used for lining, fold them the same size as the endpapers, rub paste along one edge of the fold (a width of not more than three-sixteenths inch), paste carefully to the lined side of the end-papers, the two folds being in contact up to their extreme edges. The paste should be allowed to set a bit before sheets are stuck together placed between two pressing boards under a weight to dry thoroughly. If the weight is too great or if there is too much paste used, it may spread between the sheets more than is intended and this causes trouble later on. We now have the colored paper folded, one side lined and two more leaves of white paper on the lined side. Open the white sheet and fold the reverse way, so that one of the white leaves now covers the unlined part of the paper. Smooth the fold firmly with a bone folder. The white leaf just turned over is for the protection of the unlined colored leaf, and is torn off when the latter is pasted down on the inside of the cover.

The Cobden Sanderson method of making end-p apers is very ingenious and of great value. It is fully illustrated and described in Cockerells book, to which the reader is referred. Other methods of making end-papers are in use and can be learned by consulting the text-books referred to.

Pasting on the end-papers: These having already been prepared, one is to he pasted carefully on the first and last sections respectively. Each end-paper being folded (the two colored surfaces in contact) we find a white leaf covering the outer side of each colored leaf. As the unlined colored leaf is to be ultimately pasted down on the inside of the board, it is obvious that the paste should he applied to the other leaf; the folded edge should be covered with thick paste for a space say one-quarter inch in width and after it has set (a few minutes) it should be pasted on the section, being flush at the head and not coming quite to the back edge of the section itselfone-sixteenth of an inch or even less being allowed. After both end-papers have been adjusted, place the book between pressing-hoards, well weighted, and let them dry thoroughly. It is desirable that this connection be a most solid one, as it is subject to considerable strain.

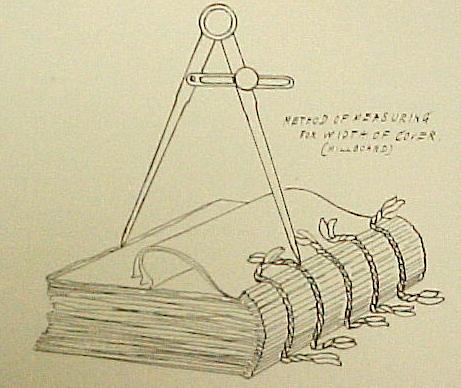

Trimming the end-papers: These being usually somewhat larger than the sections, are trimmed after being pasted on .The exact width of the sections is taken as follows, with the compass (before the end-papers are pasted on), the book laying with back to the operator: Place the thumb nail perpendicularly against back of sections, rest one leg of compass against it, with the other at the fore edge.

This distance should be marked accurately on a thin strip of paper, for reference later. The end-paper being pasted on, place a cutting tin somewhat larger than the sections between it and the sections, take the above-described measure with a compass and with thumb nail against back, mark the fore edge of each end-paper, at upper and lower ends of hook by two points with straight-edge and knife cut through them; it will then be found that the edge is true with the edge of the section. Now lay the book on a cutting board, place a thin straight-edge between hook and lower end-paper at head, the straight-edge just showing along head of the section. Press down on the book to hold it steady and cut through, thus trimming the head of end paper. After both end papers have been thus trimmed at head and tail, the book is ready for:

Fraying out the cord:

Each cord is now freed of any glue which may have stuck to it, the strands untwisted and drawn between the finger and a knife-edge or bodkin; this results in separating the strands into the original fibers, and they now present a soft, fluffy appearance.

Rounding & Backing

The sections are now knocked up again, particular attention being paid to having the book quite square at the back and at the head. It is then laid on the edge of the bench between two pieces of mill hoard which come up flush with the backs of the sections, the cords being quite covered by the boards. A thin coating of hot glue is now applied, pressure being made on the upper mill board in order to keep the glue from penetrating between the sections. Always apply the glue from center of back, toward head and tail.

Now (allowing a short time for the glue to set) lay the book on a large lithographer’s stone (Or on the bench) with the fore edge toward the operator. By placing the left hand flat on the upper surface, thumb against fore edge of central sections, the upper sections may be drawn toward the front, tapping the back in the meantime with the backing hammer, which causes the upper half of the book to assume a rounded shape.

The book is then turned over and the same process gone through with on the other side and repeated until it is “rounded” properly (the glue used for this purpose is especially prepared and does not become as hard and unyielding as the ordinary article). The back now being “rounded,” the book is laid on the bench, back away from the operator.

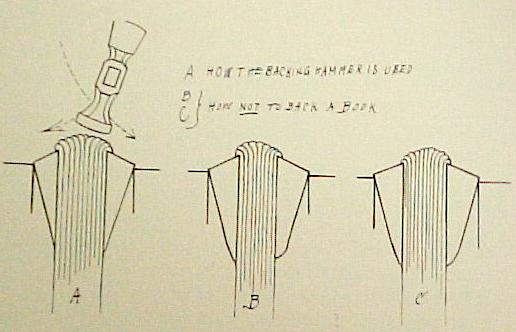

Take one of the backing irons, slightly moisten its surface, place it on the book from one-sixteenth to one-eighth of an inch from the back edge; holding the book and the iron firmly together, turn them over and adjust the other iron, moistening it also. The edges of the irons should be quite parallel. The distance from the edge of sections depends altogether upon the thickness of the book and the proposed thickness of the cover. After having adjusted the backing irons, hold them tightly, so they will not become disarranged, and place in the lying press; great care being taken to keep them perfectly parallel. The press is then screwed up as tight as possible. The cords rest on the outer side of each backing iron and care must be taken not to strike them with the hammer, else they will be cut off. With the front edge of the backing hammer (the operator standing beside the press) the sections are knocked away from the center line of back, on each side, by tapping them gently. [backing.jpg] After this has been carefully done, the face of the hammer is used (the operator now standing at the head of the press) and with blows directed alternately toward each edge of the back, the sections are gradually beaten over to the left and to the right, this finally resulting in the sections on each side being beaten down, overlapping the sharp edge of the backing irons. When finished the back of the book should be perfectly round and solid. Taking the book out of the press, we find that we have formed what are called “joints” which should be just deep enough to take in the thickness of the the board which it is proposed to use for the cover.

Putting in boards: The thickness of board appropriate to the book having been selected before the backing is done, they must now be cut to the proper size. Before doing this, each board is lined (if this has not yet been done), either on one or both sides with ordinary thin white paper. They may be lined only on one sidein which case one thickness of paper on one side only is sufficient. Again, they may be lined on both sides, in which case two thickness of paper are put on one side and one thickness on the otherthe side lined with double thickness forms the inside of the cover. This results in drawing the board on one side, the curved side always forming the inside of the cover. This drawing is necessary in order to offset the drawing qualities of the leather when it is put on the outside of the board in the process of covering.

After the boards are lined, and have become thoroughly dry, they should be cut to the proper size. Measurements for the covers should be taken before backing as follows: The book lying on the press, with the back toward the operator, the thumb-nail is placed against the back edge. With a compass (one leg resting against the thumb-nail) the distance from the back edge of the section to the front is taken. This constitutes the width of the board. Turning the book with the head toward the operator, and placing the thumb-nail against the head, the distance from the head of the section to the tail is then taken in a similar manner. An allowance is made for the “square” at the bottom of the book, which ranges from one-eighth to three-sixteenths of an inch or more, depending upon the size of the book. This should be added to the measurement last taken and this constitutes the length of the board.

It will he noted that allowance has only been made for the “square” at the bottom of the book. The “square” at the head will be made later, by cutting the head of the book after it is placed in boards. The “square” of the fore edge of the book will be made during the process of backing, inasmuch as enough of the back edge of the section is taken up by this process to make the “square” of the fore edge. These measurements must be taken most accurately and must be accurately transferred in order that the boards may lie properly. The difference of one-sixteenth of an inch in a fine piece of work would render it very defective. The best way to transfer these measurements is to register them on a narrow strip of firm, substantial paper, the lines being made with the sharp edge of a bone folder.

It is always best to cut the two covers at one operation, the two boards being kept together while the four edges are being cut. All boards should be cut most accurately in the cutting press. Lay them out with an accurate steel square, and mark with knife-edge. In order to ascertain whether they are absolutely true after cutting, one board may be reversed on the other, so that the ends which were cut together are opposite each other. If there is the slightest difference in the two boards, this method will increase it so that it will be quite noticeable. If there is any material difference, it is better to cut a pair of new boards than to try to trim up the old ones. In all cases the boards should be cut with the lined sides in contact and should be marked on the inside so they may be placed in the same relative position when lacing them to the back. The boards may he laced on after cutting the back edge only, the remaining portion being cut to size after, just before putting in leather. I prefer the former method.

FORWARDING: Head-Bands, Single & Double

Edge gilding:

Edges may be “full gilt,” “gilt in the rough,” or only have the head gilt. Full gilt edges are not in common use; this style is mostly used in religious books and in very elaborate, showy publications. “Gilt in the rough” means that the rough edges of band-made paper are gilded untrimmed. Valuable editions, etc., are not trimmed, but gilded in the original sizes. This gilding is done before sewing. The style most popular is to have the head gilt, which is done principally for the purpose of catching the dust as the book stands upright on the shelves and allowing it to be easily rubbed off. The head should be gilded just after the boards are laced in and the head has been cut.

Gilding the head:

Throw the boards back, place gilding boards on each side of the head flush with the surface to be gilt; screw up very tightly in the press. (A regular gilding press is made, which has metal instead of wooden screws, which exert much greater pressure. The amateur can, however, get along with the lying press.) The head is scraped and sand-papered. Take a piece of gilder’s red chalk, rub with water on a stone, to make a somewhat thick paste, which must be thick enough not to run between the leaves. Apply it with a stiff brush (with short bristles). When dry, brush again with a stiff brush, which removes the superfluous chalk and polishes the edges somewhat. Glaire the whole, or part of it, and apply the gold-leaf (previously cut to proper size), and let it dry. In an hour or two it may be burnished with the agate burnisher. It is well to lay an oiled paper on the gold when beginning this operation. It may also be finished through this thin paper; it will then not be so bright, but rather of the “dead gold” order.

In commercial work, and also in much work done by private binders, edge-gilding is usually sent out to be done by houses which devote their entire time to this special work. I advise the beginner not to gild the edges of his own books for the time being, but to have it done by experts in that particular line. It is much more satisfactory, as a rule, than to do it ones self.

Head-banding:

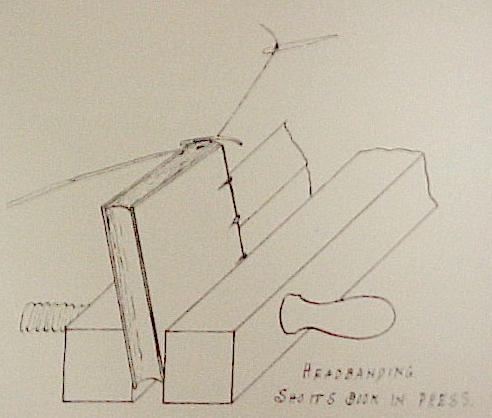

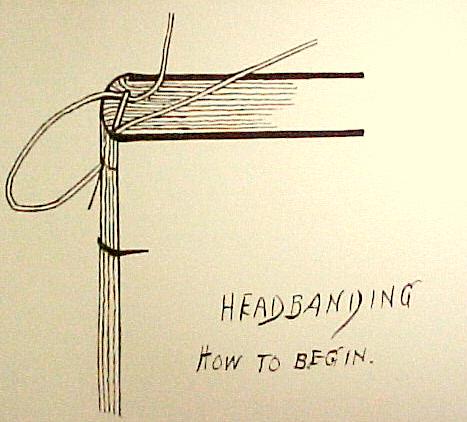

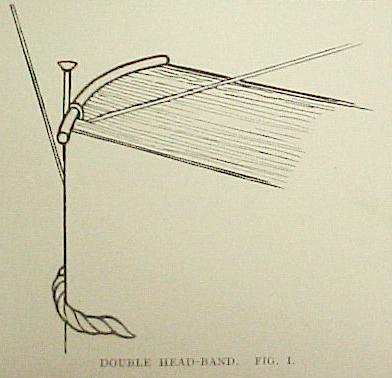

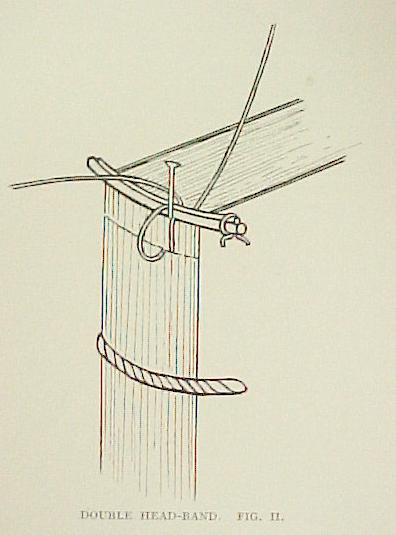

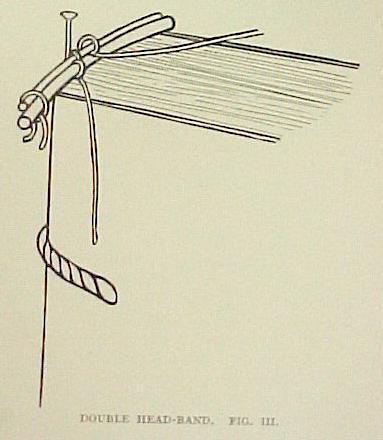

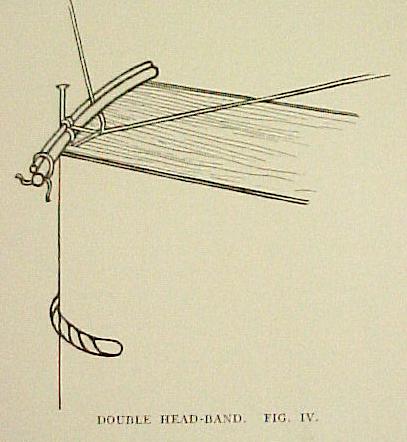

This is one of the most troublesome operations which confront the beginner, and it is almost impossible to learn to become proficient in it without some personal instruction, or at least seeing some one else do it. The silk used for head-banding should be what is known as buttonhole twist, heavier than the ordinary. No. B E is not too heavy. The simplest head-band is made as follows: Two strips of vellum are cut (using very sharp knife and rule) slightly longer than the round of the back. The height of the strip should be a shade less than the width of the squares at the head and tail. These strips are made to assume the curve of the back by drawing them between the finger and a rounded surface, such as a lead pencil. The silk used for covering these strips of vellum is usually of two colors, though more colors may be used as one becomes expert. For the purposes of explanation, however, we will assume that two colors, red and white, are used. The book is to be placed in the finishing press or other convenient press, the head up, with the fore edge slanting toward the operator (see illustration).

Two threads of silk are knotted together, and the red one threaded in a sharp pointed needle. Slip a bone folder between the leaves about five pages from front of book and pass needle through the back of book, just below the kettle-stitch. (The place where the needle is passed through the back is usually about one-half section from the front of the book.) As the thread is drawn through the back the knot is drawn between the leaves (to the front of the kettle stitch). The needle is then brought up over the head to the front, again passed through the same place, thus leaving a loop over the head of the book.

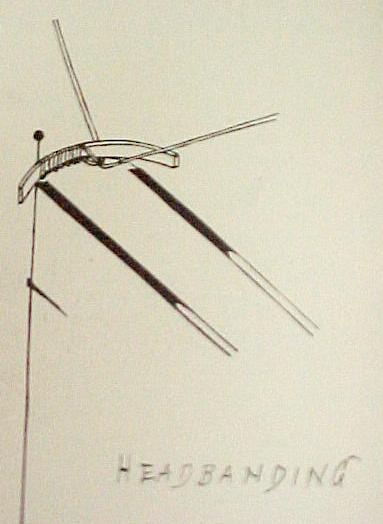

Through this loop is passed the little strip of vellum, the lower edge setting snugly on the head of the sections. The loop is then drawn tight, and this, aided with the finger holds the vellum strip upright in its proper position. By reference to the cuts it will be noted how the vellum strip may also be supported by sticking a pin or needle upright in the first section. We now bring the needle to the front again, which brings the red silk for the second time over the head-band alongside the first turn. By placing the forefinger of the left hand on this strand and holding it down on the head of the book (a little distance from the head-band), it is kept taut; with the right hand the white silk (coming up between the sections in front of the headband) is drawn over to the right over the red silk, slipped under the right-hand end of the vellum and drawn snugly down until the red silk, where it is crossed by the white, is drawn down to the junction of the edge of the strip and the head of the book. Still holding the red silk under slight tension with one finger, another finger of the left hand may be placed on the white silk (where it passes over the vellum) to hold it in place, while the end is again brought forward and again slipped under the vellum and the end brought over and down against the head of the book (as the red silk was); the red silk is then carried to the right, above the white, and slipped under the vellum as before, thus drawing the white silk to the junction of the vellum and the head of the book; then it is again brought forward and slipped once more under the right edge of the vellum, thus making two loops of red silk. The loose end of the red silk is brought forward and held to the head of the book, as before; the same operation is now repeated with the white and red silk alternately, until the head-band is finished.

The principal points to be observed in this work are, to keep both silks under constant slight tension and to see that the bead formed, where the vellum rests on the sections, is regular and not tight. If any one portion does not seem regular, it may be pushed down with the edge of a folder. From time to time it is necessary to fasten the head-band to the book. This is done every one-half inch or so, by running the threaded needle down in the section and under the kettle-stitch and bringing it out through the back and up over the head-band, as in the beginning. This takes the place of one of the turns just described, and does not interfere with the general operation of making the head-band. When the right-hand edge of the back is reached the needle is passed below the kettle-stitch (within four or five pages of the end of the book) twice, just as it was in beginning the head-band. After the needle has come out at the back the second time it is passed under the two strands of silk which now extend from the head-hand to the kettle-stitch, on edge of the back, and then down through the loop which is formed, drawn tight, and cut off. The remaining end of white silk is drawn under the right-hand end of the vellum (between the lower edge of the vellum and the head of the book) and passed through the loop of red silk just before it is drawn tight. This holds both ends snugly. That they may not slip, a bit of glue or paste may be rubbed over them at this time. When this head-band is finished we find alternate rows of red and white silk (two threads each) with a beaded margin at the base, covering the junction of vellum and sections.

Double head-band:

This may be made of vellum or cord, as desired. The upper band should be the smaller both in height and thickness. Begin by making a loop (as in simple head-band) into which the lower cord or band is slipped, the thread then being drawn tight.

Place the upper segment in position, tying the left-hand ends together to hold it. Pass the needle between the two bands, make two turns about the upper band, leaving the needle end projecting between the bands (in front). Holding it taut, draw the other end across it, passing above and to the right and under the lower band. This draws the needle end down to the junction of the lower band and the sections and commences the “beading.”

Now bring the end which has just passed under the band to the back, between the two bands, to the front, then once around the upper band, thus coming out again in front, between the two bands. The needle end is now passed across the loose end (above it) and towards the right, repeating this process as in the single head-band until it is finished.

This style of head-band is fastened to the book in the same way as was described for the single head-band. The fastening down can only be done when the needle is brought in front, between the two bands, just after it has been wound about the upper segment. Pass the needle through the section coming out on back just below the kettle-stitch; bring it up and forward between the two bands and then wind around the upper segment. At the end, after the last fastening down, the two ends are drawn under the lower strip, cut off, frayed out a bit and pasted down.

There are many varieties of head-bands, some made with several colors of silk, others made of two pieces of vellum; of a piece of vellum and a piece of catgut, lying in front of it.

The various illustrations give a fair idea as to how the silks are handled in making both single and double head-bands. Lining back: After the head-band has been made and fixed by rubbing a little glue on it at the back (thus fixing the threads to each other and the band to the upper edge of the back), the back is usually “lined.” This is for the purpose of strengthening it, and also, when false bands are used (when the book is sewn on sunken cords) to make a surface to which the bands may be glued. Place the book in the finishing press, cut a piece of paper (somewhat firm, like cartridge paper) an inch longer than the book and about five times the width of the back. Dampen one side by sponging slightly with water. Glue the back (head-bands and all) with thin, very hot glue; put the paper on the back, leaving exposed on one side a strip of the back about one-eighth inch wide; smooth the paper down well, fold it over the back again (the folded edge of the paper coming exactly at the edge of the back and parallel with the cover) the paper being smoothed down will also stick along the other edge of the back because of the strip of glue which was left uncovered in the beginning. Fold again at this edge, brush the back again with glue, and draw the paper again across the back. It is now well smoothed down with a folder and the remainder cut off smoothly along the joint. Thus we have three thickness of paper on the back, two thickness, however, lying against each other not glued. This is for the purpose of forming what is known as a “hollow” back. This arrangement allows the back to open without bending the leather and thus prevents the tooling being injured. After a short time the parts projecting, beyond the head and tail are cut off.

FORWARDING: putting in Boards & Trimming

Lacing in:

The boards now being cut to size, each edge of each board should be filed off somewhat, either with a coarse file or with a piece of fine sandpaper fastened to a small, flat piece of wood. This takes off the “burr” left from the cutting and also the sharp edge of the lining paper. Each board is now fitted in the groove where it is finally to be lacedthe head of the board being flush with the sections (cutting the head later will make the square). Place a weight on the board, take the first cord, hold it upright and at its center mark the edge of the board with knife or folder. Repeat this with each cord (mark the boards, if not already done, so each one will he returned to its proper side).

The marks for the cords should extend at right angles, say three-quarters of an inch toward the center of the board. Lay the board on a thick stone, marked side up and away from the operator, and flush with the further edge of the stone. With a rather large coarse file (12inch), file each mark made above, to a depth which will allow the cords to lie in it and be flush with the surface of the board. These grooves are necessarily deepest at the edge of the board, and gradually become shallower until they disappear.

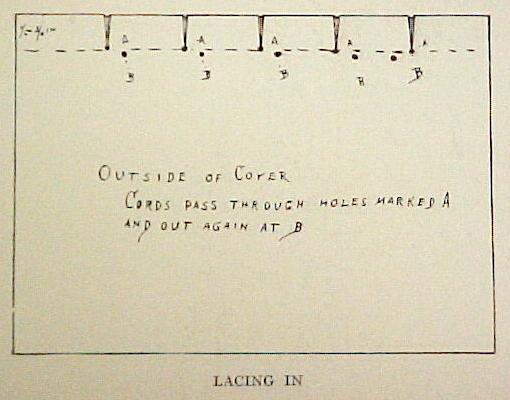

Now lay the board, grooves up, on a piece of wood or lead and with a pointed steel bodkin and hammer punch a hole in each groove at points shown at A. Reverse the board and make another set which come out at points marked B. Care should be taken not to smooth down the board around these holes where it has been pushed up by the passage of the bodkin. The cords being already frayed out, those on one side should be well pasted (to within one-half inch of the back). Holding each one near the loose end (only) is to be twisted to a point so it will easily pass through the holes just made. Place the book on the bench, back away from the operator. Raise the board at right angles to book, pass each cord through the holes A in the grooves, draw through and pass back again through the holes Beach one being drawn as snugly as possible. Now raise cover slightly and slip a heavy pressing tin on the sections under the cover, the edge, however, not quite reaching to the bottom of the groove or joint. Again raise the cover nearly to a right angle, push it into or against the joint; steady it with the chest. Each cord is again pulled as snugly as possible -especially the first and last- pressing the end (after it is pulled up snug) with one finger. When all are pulled tight, still pressing on the cord ends (to hold them taut), push the cover down flat. Still holding at least two of the ends with the left hand, tap the cords smartly with small hammer or end of knife handle, where they enter and emerge from the holes. This packs the board about the cords tightly enough to hold them in situ temporarily. Raise the end of each cord gently and cut off by running a sharp knife flat along the board, edge away from the back, so the real cords will not be cut accidentally.

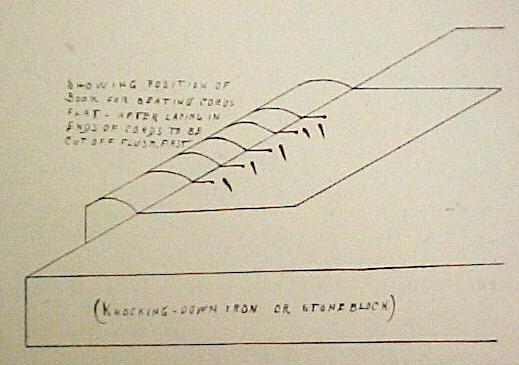

Take the book in the left hand with one cover open at right angles to book, rest it on the beating stone or other solid bed (see illustration). With the backing hammer beat the cover over the holes until the surface is smooth to the touch and no raised spots are apparent. Care must be taken not to mar the board with the hammer edge. Turn the board over and hammer the holes on the inside until they also are smooth.

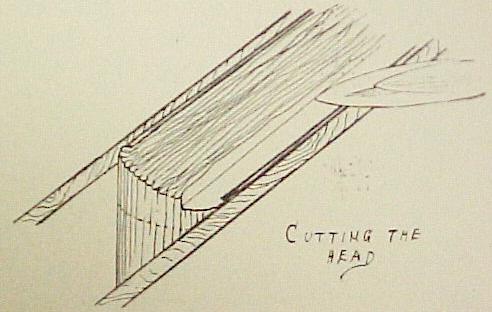

The cords are now anchored so strongly that they will break before pulling out. [lacing2.jpg] Cleaning off the back: After the lacing in is completed, the superfluous glue on the back may be removed by moistening it slightly with water, then rubbing it off with a sponge; care should be taken not to wet the edges of the boards. When well cleaned, glue should only be visible between the sections; the back should he quite clean and firm. Cutting the head: Slip a thin millboard between the head of the last section and the cover, flush with the cover. With the book lying head away from the operator, raise the front cover (to loosen the tension on the cords), slip it down, exposing enough of the sections to allow for the “square” at the head and close it again.

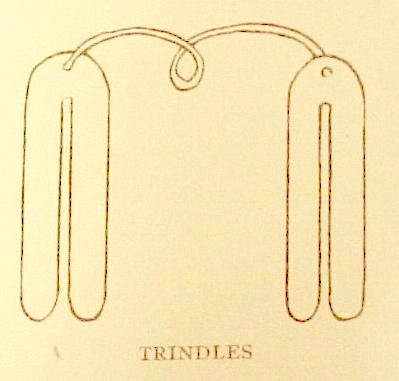

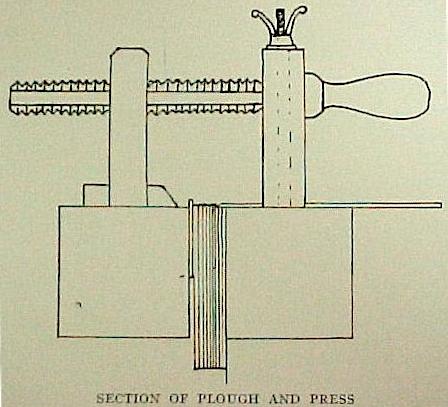

Now place the book in the cutting press, back toward the operator, the head of the front cover being flush with the cheek of the press. Be sure before screwing up the press that the two covers are quite parallel at the head, though not at the same level. [plough.jpg] With the plough cut the head, a few sheets only at each stroke, until the knife touches the slip of mill board which was inserted to protect the back cover. Cutting fore edge (in boards): The boards having been laced on, a mark is to be made (near head and tail of fore edge), with knife or folder, at edge of each board as a guide. After knocking the back as flat as possible, drop both boards away from the sections and slip a pair of trindles (see illustrations) between the back and the boards.

These trindles will keep the back flat until the sections can be snugly held by winding a tape around them. Now remove the trindles and place a cutting hoard on each side of the fore edge and place in the cutting press. The board on the side the cutting begins on must not come up to the marks; but allowance is to he made for the “square,” and when in the press this board must be flush with the cutting edge. Great care must be taken that the book is square in the press, else the operation will result in damaging it beyond repair. Errors may be avoided by comparing the side to be cut (amount of paper showing) with the other one, where a corresponding width of the cutting board should show. After the press has been screwed up tight, it is well to look at the back to see whether it may not have slipped back to a curve; also cast the eye along the edge to be cut, and note whether the width shown is equal to the amount of the other cutting board exposed above the edge of the press. If it is well adjusted the cutting may be done, cutting but two or three leaves at each cut. The knife used for this purpose should he kept in extra-good condition and never used for cutting mill-board. If a book is found to be unevenly adjusted, it is best to take it out and begin anew.

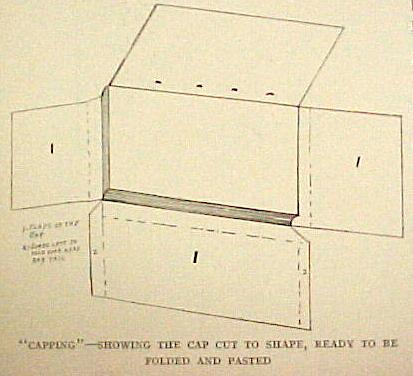

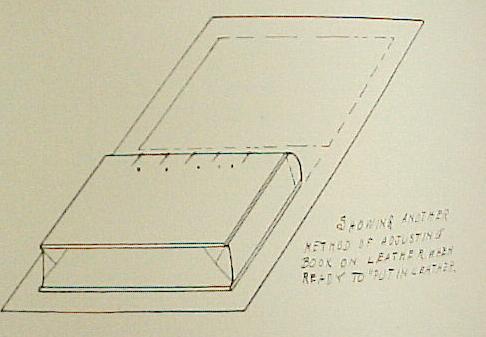

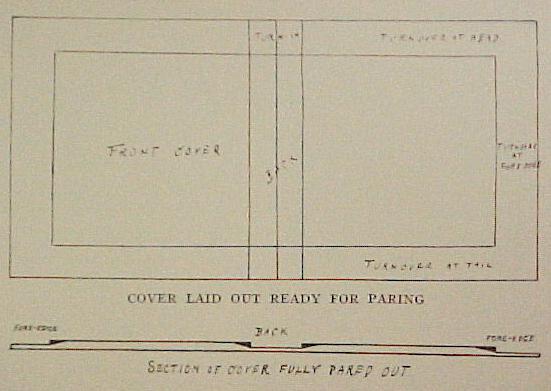

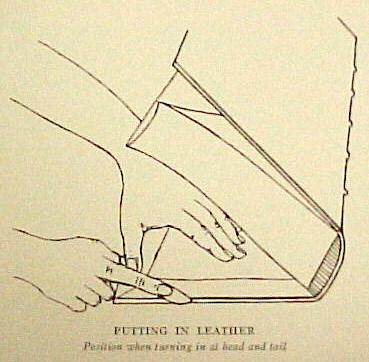

Covering, Protecting the sections while covering (capping):