Various Technical Stamping and Printing Processes.

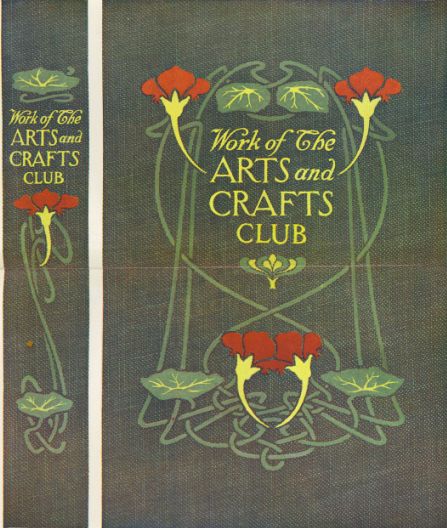

Printed bookcovers offer the greatest opportunity for designers, as it is commercial work that pre?sents the greatest field for this class of craftsnen. Printed bookcovers are executed on paper, parchment, cloth, canvas, leather, and sometimes even on ?wood. These covers are printed or stamped vvith a special press using brass dies, zinc plates, or electrotypes, according to the character and quality of the work required. The designer must know which of these methods is to be used when he prepares his design. as its commercial practicability depends almost entirely on this knowledge. Where brass stamps are used, the design is cut into thick brass plates in high relief and stamped directly on to the cloth or leather on the die press. As the cutting of these plates is accomplished largely by hand, their cost is great. It is occasionally necessary, for small editions, to use zinc plates, made by a photographic process, to stamp the design.

Zinc being softer than brass, it is less durable, and soon becomes worn, so that the printed design loses sharpness at the edges. Therefore, the designer must embody in his design such a character of line and mass as will not become seriously impaired when these edges become indistinct. The wear is not so great on the brass dies in high relief, and can be rectified somewhat by grinding down the die after its surface shows the effect of frequent compression; but the relief in the zinc plates is so slight that a new etching is necessary as soon as the wear becomes serious.

For this reason, printed bookcovers must never be executed in fine or delicate lines with the intention of showing fine gradations of shade or softness of detail. Bold con?ventional forms with large masses properly distributed give the best effect and produce the most durable dies. A design like that shown in Fig. 21 might be very satisfactory for a conventional illustration within the book, but should be reduced to the form shown in Fig. 22 before it will be acceptable for a cover design. Where a design is executed in more than one color, a separate die is necessary for each color, and a separate print?ing for each die; therefore, the cost of reproduction is multi?plied accordingly. The fewer colors used to produce a good design, other things being equal, the more attractive will be the design to the purchaser, on account of the cheapness of its reproduction.

PREPARING THE DRAWINGS

Evolution of a Bookcover Design.

The cartoon, or original drawing, for a bookcover design is submitted to the prospective purchaser as a finished representation of the design itself after it has been applied to the book, whatever may be its cover material. If the volume be an octavo, 6 inches by 9 inches-such as the I. C. S .. Reference Library-a piece of paper, canvas, or leather is cnt to exactly this size and mounted on heavy cardboard considerably darker in color than the cover itself. This represents the plain bookcover on which the design is to be executed in pen and ink, black and white wash, water color, distemper; or crayon, according to the medium best suited to represent the finished cover. The back of the book (not the reverse cover, but the back on which the title is printed) is laid alongside the cover design in the form of a long strip of paper, cloth, or leather, the exact height of the book and of a width corresponding to its thickness, on which is to be shown the character and distribution of the design on this portion. If the design on the reverse cover of the book is different from that on the front cover, it also is laid out along the side of the book back, as shown in Fig. 23.

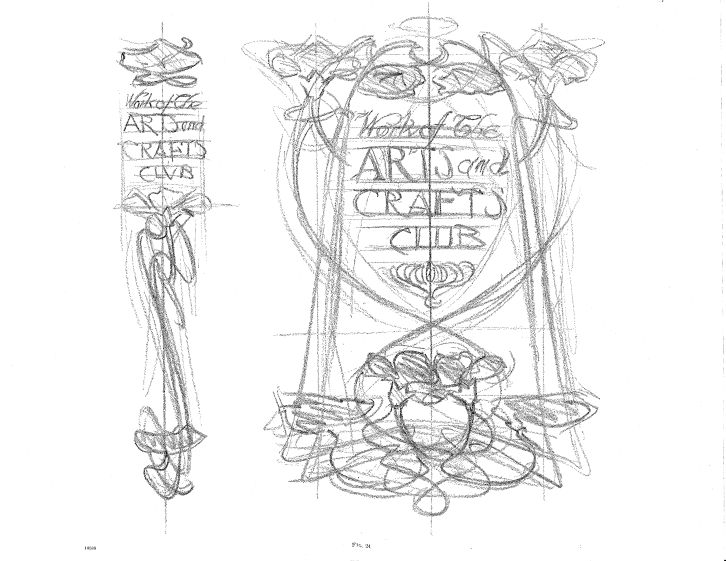

With this material cut to the required size and representing the blank form to be decorated, the designer makes a preliminary sketch, full size, of the cartoon, simply feeling for graceful lines, and roughly plotting in the masses. This roughly plotted scheme simply suggests the character of the lines and the proportioning of spaces, as shown in Fig. 24,

With this material cut to the required size and representing the blank form to be decorated, the designer makes a preliminary sketch, full size, of the cartoon, simply feeling for graceful lines, and roughly plotting in the masses. This roughly plotted scheme simply suggests the character of the lines and the proportioning of spaces, as shown in Fig. 24,

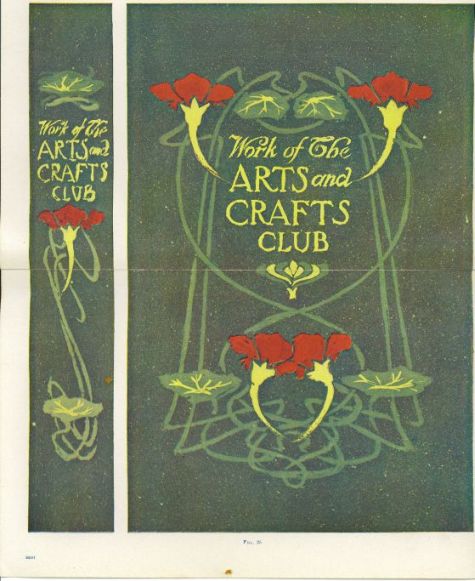

where the ornament is indicated by a few bold lines, the lettering simply indicated in a blocked space, and the general distribution of the work laid out in pencil on ordinary brown paper or tracing paper, in order to get a pleasing proportion of the design and background. This can then be worked up into general detail with color effects suggested in broad even tones, as shown in Fig. 25,

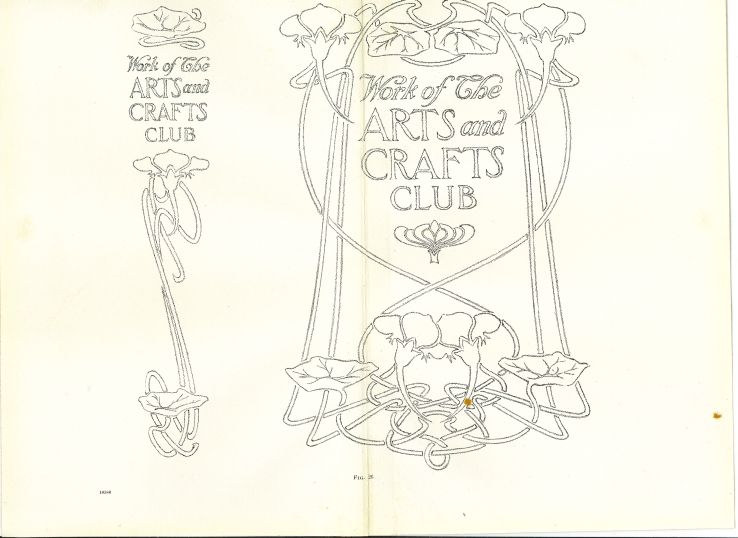

but with no attempt toward the completion of the detail. Having worked this up to the required degree, a piece of tracing paper may be laid over the rough drawing, and the principal features of the design traced from the rough sketch and afterwards carefully and accurately worked up, as shown in the outline pencil drawing, Fig. 26.

If the design of the cover be symmetrical, a center line can be drawn from top to bottom and only one-half of the design need be traced on the tracing paper, as this can afterwards be transferred to the other half, forming a completed symmetry. This tracing should be transferred to the blank cover shown in Fig. 23 by means of transfer carbon paper. This can be obtained in several colors, and a tint should be selected that will just show dimly the outlines when transferred on the finished fabric, so that there will be no danger of these outlines becoming obtrusive in the finished cartoon. If the fabric be light in color, such as white paper or light cloth, the tracing itself may be used as a transfer paper if the pencil with which it is executed has been sufficiently soft. It is best usually to make the letters of the titles on a separate paper and transfer them separately unless the designer is expert in this line of work, and can safely work them out on his original sketch. Having the outline and lettering transferred, the design should be painted in bold flat tints. Where cloth, leather, or heavy paper is the material of the binding, the colors should be Chinese white, distemper, oil color, or gold, according to the circumstances. The edges of the ornament must be clean cut, sharp, and in every respect a representation of what will appear on the finished die, and when the entire cartoon is complete it should be carefully protected by a sheet of thin paper pasted at one edge that will preserve it from injury.  Fig. 27 shows the completed cartoon, which is an exact representation of the finished bookcover. A cover of this character when purchased by the publisher is turned over to the die cutters; they select each color and cut the die therefor without separate drawings, but it is always advisable to submit with the design a table of colors consisting simply of a series of small squares about t inch, each representing an individual color used in the design, so that there can be no mistake as to the number of dies required .

Fig. 27 shows the completed cartoon, which is an exact representation of the finished bookcover. A cover of this character when purchased by the publisher is turned over to the die cutters; they select each color and cut the die therefor without separate drawings, but it is always advisable to submit with the design a table of colors consisting simply of a series of small squares about t inch, each representing an individual color used in the design, so that there can be no mistake as to the number of dies required .

DESIGNS FOR ZINC ETCHINGS

When zinc etchings are to be made for printing on cloth or paper covers, the original design submitted to the publisher is executed in precisely the same manner as where brass dies are the means of reproduction, but the design must be carried further and a separate drawing made for each zinc block that is to produce a color. After the cartoon is complete, the designer must prepare on white bristol board a silhouette of each part of the design that is to be printed in a separate color. These silhouettes should be made about two or three times as large as the reproduced cover demands. Thus, a book 6 inches by 9 inches will require a drawing 12 inches by 18 inches, or larger. in order to get the best results.

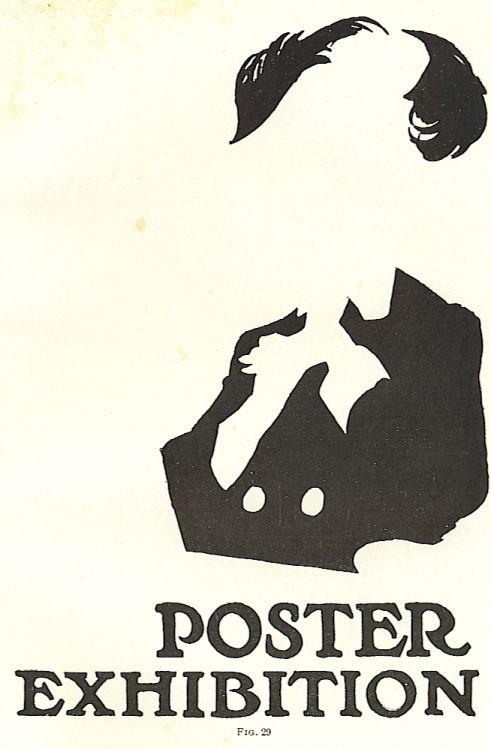

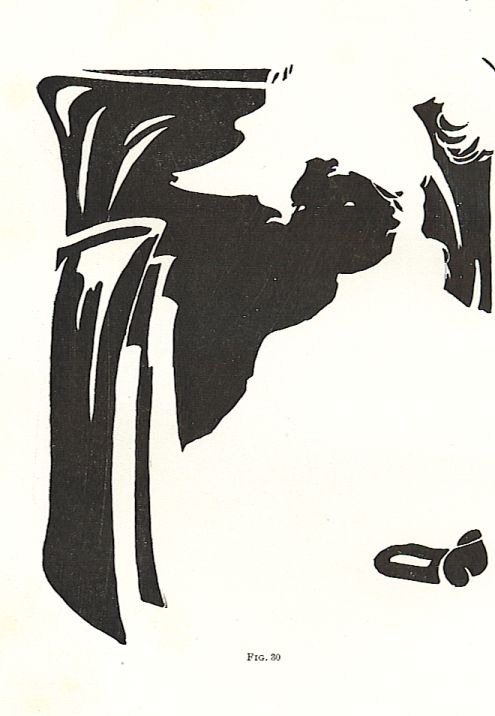

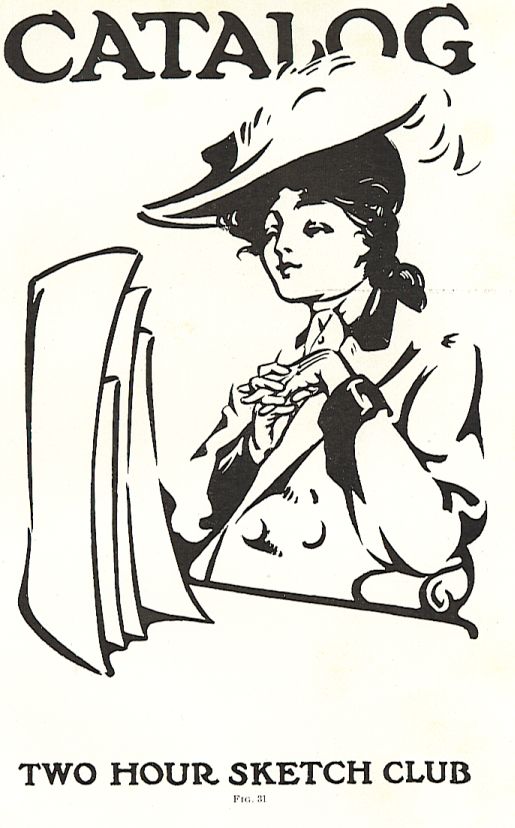

To insure accuracy in these plates, a large sized drawing should be made of the entire design, and the section representing each color should be carefully traced, transferred to the bristol-board sheet, outlined, and inked with black drawing ink. In Fig. 28 is shown a bookcover in three colors made with three impressions from zinc plates. The drawing for each of these colors is shown in Figs. 29, 30, and 31, Fig. 29 having been used for the red, Fig. 30 for the buff, and Fig. 31 for the black. Occasionally where gold is to be used in a design, zinc plates are prepared for it also, but as a gold application requires an exceedingly heavy pressure it is customary to make electrotypes of the plates so that the duplicates can be obtained when the ones in use become worn.

PAPER COYERS

Periodicals, magazines, catalogs, and certain cheaper forms of books are bound in paper covers, the printing of which is usually done from zinc plates made from pen-and-ink drawings or block drawings, as above described. Paper covers can also be executed in three-color half tone, which requires simply a photographic reproduction on three plates based on the color theory, and-with a combination of red, yellow, and blue inks will affect sufficient variation in color to depict any multiple color design. Designs of this character require accui”ate printing so that the parts represented by two or more colors register exactly. The designer in executing this class of work should bear in mind that as the selection of color values is of a mechanical character, the human eye cannot make a proper analysis of the color combinations without the aid of chemistry. He should execute his designs with the simplest combinations of color possible. Tones that can be effected by a combination of two colors should be used as much as possible, and attempts at great brilliancy or naturalism should be avoided, giving preference to the conventional forms and the flatter tones, to insure good reproduction. To insure accuracy in these plates, a large sized drawing should be made of the entire design, and the section representing each color should be carefully traced, transferred to the bristol-board sheet, outlined, and inked with black drawing ink. In Fig. 28 is shown a bookcover in three colors made with three impressions from zinc plates.

The drawing for each of these colors is shown in Figs. 29, 30, and 31, Fig. 29 having been used for the red, Fig. 30 for the buff, and Fig. 31 for the black.

Occasionally where gold is to be used in a design, zinc plates are prepared for it also, but as a gold application requires an exceedingly heavy pressure it is customary to make electrotypes of the plates so that the duplicates can be obtained when the ones in use become worn.

PAPER COVERS

Periodicals, magazines, catalogs, and certain cheaper forms of books are bound in paper covers, the printing of which is usually done from zinc plates made from pen-and-ink drawings or block drawings, as above described. Paper covers can also be executed in three-color half tone, which requires simply a photographic reproduction on three plates based on the color theory, and-with a combination of red, yellow, and blue inks will effect sufficient variation in color to depict any multiple color design. Designs of this character require accurate printing so that the parts represented by two or more colors register exactly. The designer in executing this class of work should bear in mind that as the selection of color values is of a mechanical character, the human eye cannot make a proper analysis of the color combinations without the aid of chemistry. He should execute his designs with the simplest combinations of color possible. Tones that can be effected by a combina?tion of two colors should be used as much as possible, and attempts at great brilliancy or naturalism should be avoided, giving preference to the conventional forms and the flatter tones, to insure good reproduction. Covers executed in black and white are drawn one and one-half to two times the size of the finished product, in precisely the same manner as illustrations are made for the text. They may include any variety of conventional or naturalistic rendering that may be desired, as the reproduction is absolute and there is no uncertainty as to what the result will be when the plate comes from the photoengraver.

Bookcovers designed in half tone may be made from wash drawings but should be preferably executed in distemper, composed of Chinese white mixed with ivory black to give it depth of color, to which a sufficient amount of Indian rcd has been added to give it a decided reddish tone. This is of vast importance, as in the process of photoengraving the reddic:h value in the drawing produces greater contrast than grade values that tend tmvard blue; a mixture of some inks with Chinese white produces a grade value of a bluish tone that looks perfectly well in the original drawing but reproduces with little contrast. In order to avoid such discrepancies, it is best that all distemper color applied to the shaded drawings possess a decidedly red tone, as there can be no question as to how it will appear in the finished tint.

REQUISITES IN DOING SUCCESSFUL BOOKCOVER DESIGNING

The commercial success of the bookcover designer depends on his own indi vidual characteristics and the impression he makes on his prospective purchaser, quite as much as on his skill as a designer and his talent as a draftsman. There is a certain element of egotism in every individual, and the designer must appeal to that element when he submits his cartoon to the publisher. For this reason it is advisable for the designer to come in personal contact with the person in the publishing house that makes the decisions as to what designs shall be used and what shall not be used in the ornamentation of certain books. This acquaintanceship will soon apprise the designer of the character of the work that will appeal to this publisher and he can work up his schemes accordingly. All designs must be executed with mathematical accuracy, and must be neatly and carefully mounted so as to show them off to the best advantage, as a prospective purchaser will consider the design attractive to the public in the same proportion as it is attractive to himself. accordingly. All designs must be executed with mathematical accuracy, and must be neatly and carefully mounted so as to show them off to the best advantage, as a prospective purchaser will consider the design attractive to the public in the same proportion as it is attractive to himself. In making a design for any especial title, the designer must not lose sight, in his endeavor to fit the design to the title, of the individuality and attractiveness of the bookcoyer. The attractiveness of the cover may lead the reading public to study the title after they have been attracted by the design. A glance into a bookstore window where many books are displayed for sale will reveal the fact that there are many designs there that attract attention over and aboye other designs, not that they are especially beautiful, but are certainly more prominent. If, in addition to this, the design is in harmony with the title and suggests interesting subjects between the covers, it is likely to assist in the sale of the book, and probably appealed to the publisher ,vhen he selected it.

The novice in designing should analyze every bookcoyer and bookcover design that he sees, not with a view to copying the idea, but to the end of learning what was in the designer’s mind when he conceived it; also, what there was to it that induced the publisher to use it. This analysis should not only be made from an artistic standpoint, but also from the practical side of the printer, die cutter, photoengraver, and others concerned in its reproduction. An analytical study of this character will also train the inexperienced designer to detect the defects in printing books from old dies, and the deterioration in design due to worn edges on the plates and blocks will be readily observable.